Why Hurricane Melissa is so dangerous

Rachel Hagan and

Mark Poynting,Climate Reporter

Getty Images

Getty Images

A very powerful hurricane is creeping towards Jamaica with anticipation that it will be the strongest storm to hit the Caribbean island in modern history.

Hurricane Melissa, now a Category 5 storm, is approaching the island’s southern coast with maximum sustained winds of 295km/h (185mph) – the strongest on Earth so far this year.

Those speeds are above those of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, one of the worst storms in US history.

For a nation already living on the front lines of a changing climate, the threat is grave.

So will the nation withstand its impact?

How did the hurricane form?

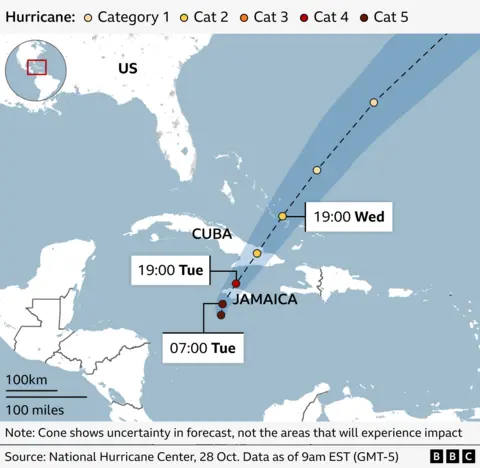

Tropical Storm Melissa took shape last Tuesday before rapidly strengthening as it moved west through the Caribbean.

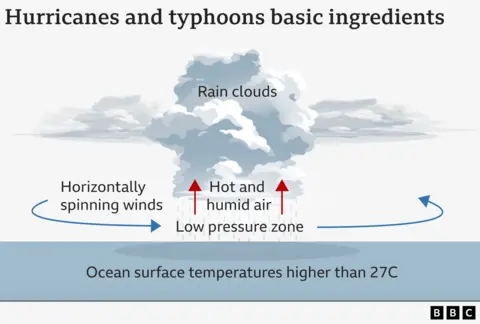

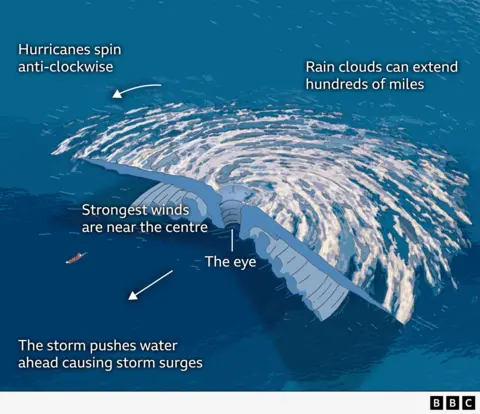

A hurricane forms when warm, moist air rises from the ocean surface and creates a spinning system of clouds and storms. In the centre, air sinks, creating the eye, a calm, cloud-free zone surrounded by a wall of violent winds and rain known as the eye-wall.

Melissa’s origins trace back to a cluster of thunderstorms off the coast of West Africa in mid-October. By 21 October it had reached tropical storm strength and by the following weekend, it was a Category 4 beast churning through the Caribbean Sea.

Ocean temperatures in the Caribbean are unusually high this year and hurricanes feed off that warm layer of water. Those conditions allowed Melissa to intensify quickly, growing from a storm into a Category 5 in under a day.

“The ocean is warmer and the atmosphere is warmer and moister because of [climate change],” says Brian McNoldy, senior research associate at the University of Miami.

“So it tips the scale in favour of things like rapid intensification [where wind speeds increase very quickly], higher peak intensity, and increased rainfall.”

How does Melissa compare with other storms?

Melissa ranks as one of the strongest storms in the Atlantic this century.

For Jamaicans, the comparisons with past storms are chilling. If it strikes Jamaica at close to full strength, it could eclipse all the storms the island has experienced before. Gilbert in 1988, the last direct hit, was a Category 3. It destroyed thousands of homes and killed 49 people. Dean in 2007 and Beryl in 2024 came close, but neither matched Melissa’s power.

The storm’s central air pressure dropped to 901 millibars as of the National Hurricane Center’s advisory on Tuesday morning, just below Hurricane Katrina’s 902 mb. The lower the pressure, the more violent the winds – making this one of the most powerful systems ever to form in the Atlantic.

Hurricane Katrina, which hit New Orleans in 2005, killed 1,392 people and caused damage estimated at $125bn (£94bn).

“This is going to be the strongest hurricane that’s ever hit [Jamaica], at least in the records we have,” Dr Fred Thomas, a research software engineer at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, told the BBC.

The storm has been blamed four deaths in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Jamaica’s minister of health said on Monday that three people had died on the island while preparing for the approaching storm.

Melissa strengthened particularly quickly. The storm’s wind speeds increased from about 71mph to 139mph on Sunday local time, before rising to 185mph on Tuesday afternoon. Fuelled by exceptionally warm waters in the Caribbean, around one to two degrees above average.

“There has been a perfect storm of conditions leading to the colossal strength of Hurricane Melissa,” Dr Leanne Archer, research associate in climate extremes at the University of Bristol, said.

Why is it going so slow and what does that mean?

While the wind speed is staggeringly high, the storm’s movement is notably slow. Melissa itself was crawling westward at around 5km/h on Tuesday- slower than a person’s walking pace.

That lethargy, meteorologists warn, could be catastrophic as it means that a hurricane can bring rain to a single location for days on end, aggravating flooding.

When hurricanes stall, they linger over one area for far longer than normal, leading to repeated waves of rain, flooding and wind damage.

One of the most famous examples of this is Hurricane Harvey in 2017, which stalled over Houston in the US. Harvey released 100cm of rain in just three days, causing catastrophic flooding.

The US National Hurricane Centre has warned that Jamaica could see 38 to 76 cm of rain, with as much as a metre in some mountainous areas.

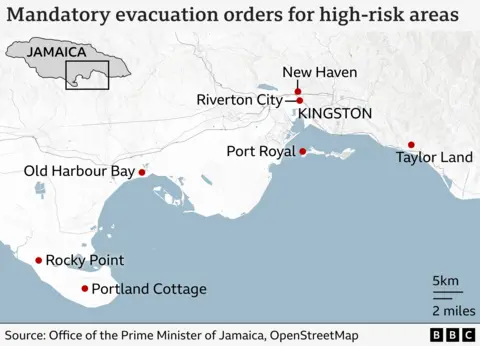

Storm surges of up to four metres are possible, especially along the island’s southern and eastern shores. Low-lying parishes such as Clarendon and St Catherine are at risk of flash flooding not only from rainfall but also from torrents rushing down from the Blue Mountains.

“Imagine a metre of rainfall coming down in a whole basin and then being channelled down into a river network. That’s going to be metres and metres of flooding by the time it reaches the lower parts of that drainage network. So the flooding will probably result in a large loss of life, I imagine,” Dr Thomas, who visited Jamaica earlier this year, said.

Some research suggests hurricanes are generally moving more slowly than they used to. That means more storms like Melissa are likely to sit, rather than sweep, over the land they hit.

And some scientists believe that might be to do with how climate change is affecting circulation patterns in our atmosphere, but that is far from certain and natural variability may also be playing a role.

Reuters

Reuters

What is the threat to the island’s infrastructure?

Jamaica’s Prime Minister Andrew Holness has already warned that “no infrastructure can withstand a Category 5”.

Dr Thomas largely agrees, but explained that most new buildings in Jamaica were made of reinforced concrete, as required by national building codes.

“Anything built to that code should be pretty strong in terms of the wind, but the wind has only one impact,” he said.

“The frightening thing about Melissa is not just the wind – it’s the rain and the storm surge. You could have your whole ground floor completely inundated and then part of the first floor as well.”

In major cities like Kingston and Montego Bay, the construction is more robust, he said, but in rural and hillside areas, “there’s more vernacular architecture [some things built from wood] not the larger, concrete-type buildings”. Those will fare far worse.

“This hurricane will be very hard on Jamaica,” says Kerry Emanuel, professor emeritus of atmospheric science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Jamaica is “unprepared to cope effectively” with major storms, Dr Patricia Green, an architect and preservationist based in Kingston told the BBC. She recalled how “a couple of hours of rainfall” in September caused “massive flooding” in the capital, exposing deep weaknesses in urban planning.

She criticised the surge of high-rise developments “sited in areas that should be the runoff of the city”, saying they had brought flooding to districts “that never had flooding before”.

As a low-lying island nation, it is particularly exposed to storms. About 70% of the population resides in coastal areas, according to data from the Jamaican government.

And as is the case with extreme weather, poorer communities are expected to be most badly affected.

“This is one of those worst-case scenarios that you prepare for but desperately hope never happen,” says Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology at the University of Reading.

“The whole country will have a deep and permanent scar from this beast of a storm. It will be a long and exhausting recovery for those affected.”

Tourism is another concern. Jamaica’s big resorts are largely made from concrete, but their strength has never been tested by winds of this magnitude.

Other parts of the country’s infrastructure are more exposed, with electricity expected to go out. Dr Thomas said: “The grid will probably take areas offline before the worst of the storm. But then you’ve got poles and lines brought down by debris and trees. It’s often not the wind itself, but what the wind picks up.”

Beyond the buildings, the storm threatens Jamaica’s power, water and transport networks. Fallen trees and flying debris are expected to down power lines. Flooding could overwhelm sewage systems and contaminate water supplies. Landslides are likely to cut off mountain roads, isolating rural communities.

Dr Green said modern architectural trends are worsening resilience and the move from traditional jalousie windows with slats to fixed glass can leave buildings more exposed. The sealed panes prevent air from passing through, increasing pressure inside and making walls and roofs more likely to fall when storms strike.

The most vulnerable, she added, are the poorer communities, particularly those living along riverbanks and gullies, which Dr Green says is a “historical, colonial issue”, tracing back to emancipation, when formerly enslaved people were granted marginal lands. Many of these families, she said, have lived there for generations, without affordable alternatives or secure land titles.

Dr Thomas pointed particularly to Port Royal which is a small fishing village in Kingston, considered one of the most hurricane-vulnerable communities and on the compulsory evacuation list.

He visited in February, explaining: “It’s sort of a long spit of land and it’s extremely exposed with a seven or eight-mile drive back to the mainland, so it could be quite easily cut off.”

The ripple effects of any one failure can be wide: “Power goes out, and then telecommunications go. Hospitals have backup for a while, but often not long enough. And the airport’s closed, which means aid can’t get in quickly.”

With airports closed, supply chains disrupted and aid flights grounded, even after the storm passes, recovery may take months.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.