The US island where you can walk to Russia

Matthew Guiffré/KNOM

Matthew Guiffré/KNOM

As Trump and Putin meet in Alaska, two twin islands connected by an ice bridge in the Bering Strait are a reminder that the US and Russia’s culture and history are deeply intertwined.

When Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with US President Donald Trump in Anchorage today, it will mark the first time a Russian leader has ever set foot in Alaska, despite the fact that the US’s largest state was actually a Russian colony from 1799 to 1867.

The summit, billed as a conversation about ending the war in Ukraine, comes more than 150 years after the US purchased the nearly 600,000sq-mile expanse from Tsarist Russia for just $7.2m (less than two cents an acre), and serves as a reminder that the two nations are far closer than most imagine.

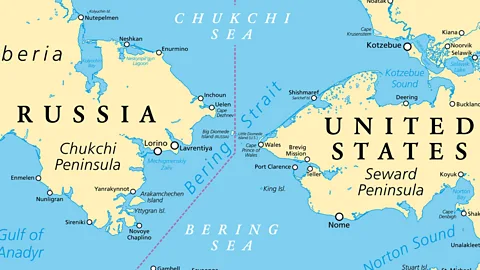

Though the US and Russia are often cast as distant rivals, their histories and geographies are deeply intertwined in America’s 49th state. In the early 18th Century, the frigid waters of the Bering Strait, just 51 miles wide at its narrowest point, served as a thoroughfare for Siberian traders, Russian Orthodox missionaries and Indigenous Iñupiat and Yupik communities who moved freely between the two continents to trade, marry and hunt.

Alamy

Alamy

Even after Alaska became part of the United States, many cultural and familial ties lingered across the divide, and today, travellers to Alaska may still spot onion-domed Russian Orthodox churches, meet residents with Russian surnames and see Russian artefacts in museums. But nowhere is this cultural and geographical proximity more striking than on the Diomede Islands.

The Diomedes are two wind-lashed volcanic outcrops separated by just 2.4 miles of sea and ice. The smaller of the two, Little Diomede, is part of the US, while the larger, Big Diomede, is Russian.

Don’t try the trek

It is illegal to travel between the Diomedes without proper documentation.

Yet, it isn’t just countries and continents that cleave the twin isles: the invisible sweep of the International Date Line also runs between them. So, despite the fact that residents on Little Diomede can see Russia from their wooden cabins and – in theory – walk across the frozen ice bridge to Big Diomede, as their ancestors did, Big Diomede is 21 hours ahead of Little Diomede, a quirk that has led locals to dub the frozen outcrops the “Yesterday and Tomorrow Islands“.

Today, Big Diomede is uninhabited, save for a Russian border guard station. Little Diomede is home to about 80 residents – most of them Iñupiat, who live in a cluster of houses perched on the western shore, the only patch of relatively flat ground between sheer cliffs and the turbulent sea. Helicopters usually deliver mail and a few supplies once per week, but fog and violent winds often delay landings for days or weeks on end. Instead, residents on Little Diomede have relied on fishing, hunting seals and walrus and catching seabirds for centuries.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons

Long before modern borders were drawn, however, both islands were inhabited by Indigenous peoples. Even after Alaska was purchased by the US in 1867, the isles functioned as one community for more than 80 years, with residents still paddling, walking or dog-sledding freely between the two landmasses.

That all changed in 1948 when, at the onset of the Cold War, the Soviet Union relocated Big Diomede’s Indigenous residents to the mainland, scattering them across Siberia. The two nations sealed the border, creating a boundary that still exists and is known as the “Ice Curtain“. Today, most of Little Diomede’s residents have relatives somewhere in Russia who were relocated from Big Diomede, and residents here still see themselves as one people separated by a frozen border.

“Families were suddenly divided across the Bering Strait,” said Charles Wohlforth, who co-authored the book To Russia With Love: An Alaskan‘s Journey, which explores Alaska’s historic ties with Russia. “These connections were broken and not reconnected for roughly 40 years.”

On June 13, 1988, the Friendship Flight marked a thaw in Cold War tensions between the US and the Soviet Union, reconnecting Alaskans and Russians after decades of an impassable boundary. A chartered Alaska Airlines jet carried politicians, dignitaries and Alaska Native elders from Nome, Alaska to Provideniya, Russia so they could spend a day reuniting with relatives they hadn’t seen since childhood and meeting family members they’d only heard about in stories.

Alamy

Alamy

“That kicked off a whole era of positive relations between Alaska and Russia that lasted about 25 years,” said David Ramseur, the then-press secretary for Alaska Governor Steve Cowper, who helped organise the flight, and more recently, the author of the book Melting the Ice Curtain: The Extraordinary Story of Citizen Diplomacy on the Russia-Alaska Frontier. “Every group you can think of, from cold-water swimmers to journalists to folk singers, put together exchange programmes to and from Russia.”

Travel to Little Diomede

Little Diomede is only accessible by boat (when the ice thaws) and by taking a helicopter from the closest airport in Nome, Alaska. A one-room stay is available for rent through the Inalik Native Corporation, and while there are no restaurants or banking services on the island, there are some groceries and fishing/hunting supplies available from the island’s only shop, the Little Diomede Native Store (though it’s better to bring your own provisions, as to not impact locals’ limited supplies). While on Little Diomede, you can explore the village, learn about traditional subsistence hunting and fishing, observe impressive colonies of seabirds (like horned puffins and black-legged kittiwakes) and purchase intricate ivory carvings famous on the island.

In the years that followed, travel between western Alaska and eastern Russia became relatively routine, with locals on either side participating in joint sporting events, scientific research and business ventures. One memorable people-to-people initiative, Ramseur noted, was The Bering Strait Expedition, which saw a team of American and Soviet skiers and mushers (including Indigenous participants from Alaska and Chukotka) cover roughly 1,000 miles from Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula to Alaska’s Seward Peninsula as a form of dogsled diplomacy in 1989. Named after an ancient land bridge that once bridged the Bering Strait, the peace project was meant to highlight the shared history and enduring cultural ties between Indigenous peoples on both sides.

More like this:

• The US island that once belonged to Russia

“Those of us in the governor’s office concocted this crazy idea to do a treaty signing on the International Date Line, standing on the ice between the two Diomedes,” Ramseur said, adding that because a winter storm rolled in, the governor’s office was stuck on the mainland, thwarting their plans. “Some journalists had flown in from Moscow to cover the event, and while they were stuck waiting for us on Little Diomede, two of them pulled an Alaska Guardsman aside and asked for political asylum. They eventually got it, but it sort of blew up all the goodwill of the expedition.”

Ramseur said that this period of neighbourliness only lasted until the early 2000s after Putin came to power and changed Russian policy to discourage interaction with the West. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, the sentiment has soured further across the state – the Anchorage Assembly voted to end a sister city relationship with Magadan, Russia, in 2023, and more recently, in Nome, a city that sits just 160 miles east of Russia, locals have been building homemade drone jammers and sewing Kevlar body armor to send to Ukraine’s frontlines. Rallies against Putin are expected in Alaska’s most populous city on Friday.

Alamy

Alamy

And though there’s still a mural on Little Diomede’s school gymnasium showing two hands joined across the watery divide between islands, with the word “friend” written in both English and Russian, the isle’s few residents are known to keep an eye on the movements of Russian troops, ships and helicopters in the area (which have increased, especially as melting sea ice has opened possible Arctic shipping), sharing their gathered intelligence with military officers in Anchorage.

Whether the Anchorage summit delivers tangible change or leaves relations frozen in place, it will be watched closely from both sides of the Bering Strait – where politics, like sea ice, can shift without warning.