The Sacramental Underpinnings of Vaccine Culture

The human capacity to sculpt the terrain that surrounds us is enormous but not without limits. While a farmer or a gardener may replace or modify the geographical and botanical features on a given piece of land, it is only quite rarely, and with the help of an enormous expenditure of very scarce resources, that he can, say, turn a sizable hill or mountain into a lake or a plain.

The work of tilling the land and making of culture are, in English and in numerous other languages, are linked on the etymological level, with both being derived from the Latin verb colere whose varied meanings include “to cultivate,” “to care for,” “to tend to,” “to honor,” “to revere,” “to worship,” or “to embellish.”

And while it would be absurd to suggest that an implied element of one derivation of a given verb in some way conditions the semantic content of another, I can’t help but wonder whether the limitations implicit in the act of cultivating the land as described above might nonetheless help us better understand those that relate to the making of culture.

In other words, could it be that there are “hard” cognitive structures and/or yearnings within us that might delimit the extent to which we can actually generate the wholesale ruptures with the past ways of being and thinking?

For example, it is quite common for historians to speak of the 19th century as the Age of Nationalism, which is to say, the time when the nation-state established itself as the normative form of social organization in Europe and much of the rest of the world.

And most of them, being secular people themselves, have sought to explain this “rise of the nation” in secular ways, which is to say in terms of grand political theories, sweeping economic transformations, the writings of intellectuals, and the actions of powerful politicians and generals.

However, a smaller number of scholars, observing the great and often bloody passions which the nation-state has evoked among the masses, and that its rise largely coincided with the first great decline in religious practice in most Western countries, have suggested that it might be more accurate to portray the nation as merely a new, secularly-inflected receptacle for timeless yearnings—such as a desire for social unity and an engagement with the transcendent—that were previously “serviced” by organized religion.

A small number from this latter group, such as Ninian Smart and David Kertzer, have gone on to analyze the myriad cultural practices deployed in the name of nationalism in light of traditional Western ritual, sacramental, and liturgical processes. Their work makes for fascinating reading.

Smart, for example, outlines several of the ways in which national movements partake of patterns common to religions. The first is to “establish the mark” which separates the believers from the non-believers. The second is to engage in performative rituals that celebrate the mark in the name of a set of spiritually “charged” materials (e.g. ancestors, war heroes, great scholars, or simply the “sacred” earth that provides sustenance to the community), rituals designed to lift the citizen from the humdrum of his everyday existence and into a relationship with forces that transcend his standard, lifespan-delimited, sense of space and time.

He also noted how the solemn celebration of the spilling of citizen blood in defense of the “marked” national terrain is customarily portrayed in this context as a sacramental act that greatly heightens the sacred “charge” within the collective while also cleansing it of some of its less desirable attributes or habits.

The end goal of these rituals, he argues, is to evoke a sense of psychic subordination in the common citizen, a lowering of the self that Smart compares to the way we—or at least those of us born before 1990 or so—were acculturated to abandon our customary modes of comportment when entering a church or another space identified as being a portal to transcendent forces. “By a kind of self-deprecation or self-restraint I reduce my value somewhat and communicate sacrificed value to what is sacred. But such proper behavior opens up the interface between me and the sacred, and in exchange for my self-deprecation I gain the charged blessing of what is sacred.”

The end result of this psychic transaction is, he argues, a “performative transubstantiation whereby many individuals become a superindividual,” a status, he goes on to suggest, that fortifies that same individual against the dissolvent forces of industrial modernity with its greatly enhanced mobility, new fast forms of communication and, paradoxically, the “voracious demands” of the very state that individual has been trained to venerate.

Kertzer, a scholar of contemporary Italy, affirms the enormous role that rituals of an implicitly religious cast play in the initial consolidation of a national identity. However, he also underscores their crucial importance, as in cases, such as Mustafa Kemal’s Turkiye or Mussolini’s Italy, where powerful elites set out to radically and swiftly overhaul long-standing codes of cultural and national identity, noting how these pedagogues of nationhood often co-opt historical tropes, that on the surface of things, often appear to be completely antithetical to their program of ideological rupture.

It is clear, for example, that strengthening the Italian nation was far more important to Mussolini than helping or supporting the Catholic Church. In fact, like most Italian nationalists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he saw the long-standing power of the church as one of the foremost impediments to achieving true national unity and power.

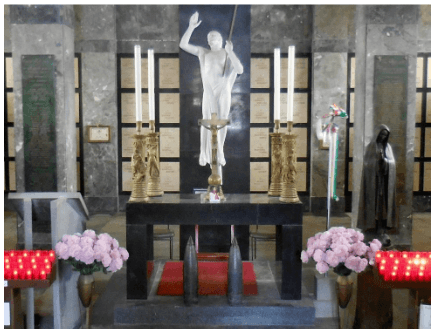

He was, however, also a very pragmatic political operator and realized that an open struggle with the church was not in his interests. The solution? To sign a concordat with the church and then to take traditional Catholic rhetoric and traditional Catholic iconography, wholly or partially strip them of their previous relational referents, and, as the photo below demonstrates, imbue them with new nationalist associations.

While it, at first glance, appears to be an image of the altar of a church, it’s actually a chamber from a memorial to Italian dead from World War I completed during the very first years of Mussolini’s long rule (1922-43).

Yes, there is a crucifix with a statue of the Risen Christ behind it. But added to these Catholic images are, incongruously, candelabras of a clearly classical iconography, designed, as Mussolini often sought to do, to link actions of his new assertive and unified Italian state to the greatness of the pagan Roman Empire, and then even more discordantly, two cannon shells that speak to the lifeblood of the modern state: military might.

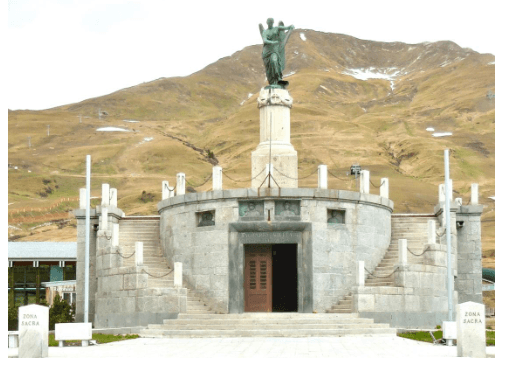

This iconographic deadlock within the crypt of the monument is broken, however, when we step outside and see a massive statue of the, again, pagan-inspired “Winged Victory,” several times larger than the structure in which the altar is located, towering over it all.

And just in case the onlooker approaching the monument should miss the message regarding the transcendent nature of what, from his point of view has no ostensible sign of Catholic iconography, there are messages engraved in stone on each side of the foyer leading to it that announce that he is entering a “sacred space.”

The message could not be clearer. The Italian leader is appealing to the deeply-rooted Catholic reflexes of the Italian public to sell them a new object of belief, the state, that he hopes will largely relegate that previous receptacle of their transcendent yearnings, the Church, to a place of secondary importance.

Reflecting on this and the many other transcendentalist bait-and-switches carried out by nationalist culture planners of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (once you begin looking, the examples are endless), it seems licit to ask whether the tactic might be in play in more contemporary attempts to generate radical change in other ideological realms of our culture.

For example, might the globalists who are seeking to abolish notions of bodily sovereignty and the intrinsic sacredness of each individual human being in their pathological drive to engender a new and more wholly embracing form of medieval feudalism knowingly and cynically appeal to our desire for transcendence in their efforts to rob us of our God-given freedoms?

I would have to say “yes,” and that vaccine culture lies at the very center of this multi-pronged effort to bring us under their maleficent spell.

The concept of transubstantiation, employed by Ninian Smart in the passage cited above, has played a central role in Christian and, therefore, much of Western thought throughout the centuries. It is used most frequently to describe the transformative powers of the Eucharist when taken into the body of the believer.

While there are differences of interpretation regarding what the eucharist is or becomes when taken into the body (Catholics and Orthodox believing it is miraculously transformed into the actual body of Christ in this moment, while Protestants see it as a potent symbolic reminder of the possibility of that same process), all of them place enormous importance on this ceremonial act.

It is viewed as the culminating event of the believer’s perpetual yearning to be rebound (the word religion is derived from the Latin verb religare, meaning to rebind or to join together) in peaceful unity with his fellow men and women and the pure loving energy of God.

Put another way, receiving the Eucharist is an act of submitting voluntarily to the “violation” of one’s individuality and personal sovereignty in the hope of escaping the limits of the self and becoming part of a supportive human fellowship and coming into contact with forces that transcend quotidian notions of space, time, and, of course, human fallenness.

This last part is key. The individual gives up his sovereignty in the belief that only positive things—healing powers that cannot reasonably be expected to come from “mere” fellow humans—will come from his act of submission.

The promise of Modernity, a movement that began during the late 15th century, lay in its belief that human beings, while still subject to the whims of divine power, had a much greater ability to control their destinies through reason than they had exhibited in the immediately preceding centuries.

As the material benefits provided by the application of scientific thinking to life problems continued to grow in the ensuing centuries, there emerged among important proponents and practitioners this way of thinking (a relatively small minority of most cultures), a belief that God, if he existed at all, did not interfere in, or materially affect, the daily actions of men.

In other words, for perhaps the first time in human history, a small but socially and economically powerful group of people, bolstered in their beliefs by the emergent doctrine of the elect within Calvinism, had declared themselves to be the true authors of humanity’s ontological destiny.

This idea of man as the master and creator of history took still more aggressive strides during the period of Napoleon’s armed assaults on the traditional cultures of the Old Continent.

However, as the Romantic rebellions of the first half of the 19th century in Europe soon revealed, a lot, if not most, people were not quite ready to consign their fates to the whims of their fellow human beings, however much these fellow human beings might present themselves as possessing exceptional foresight and talents.

And that was for a simple reason. These so-called reactionaries knew that for all of their self-proclaimed vision and omnipotence, these “progressive” elites were, as their understanding of the cycles of nature and lessons in non- and/or pre-Calvinist Christianity had taught them, still subject like all other humans to the vices of venality, greed, and the sometime desire to tyrannize others.

This recalcitrance constituted an important impediment to the plans of the would-be Gods of progress among us. And, in an effort to sell their idea of an elite-led paradise devoid of reverence for the divine, they began to cloak their appeals to “the masses” in the semiotics and ritual practices of the very religious traditions they sought to greatly weaken and eventually vanquish.

The first to do so, as we have seen, were the nationalist activists and leaders of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As the crazed rush to get maimed and killed in the name of the nation in World War I (so memorably described by Stefan Zweig in his World of Yesterday) made clear, these initial efforts to imbue the nation with religious import were quite successful.

But the grotesque carnage of that conflict and that even more destructive one that followed it only 21 years later robbed the nation of much of its transcendental “charge.”

In its place, under the new American-led global empire, science, and especially medical science, was promoted as the new secular receptacle of Western culture’s perennial, if now systematically muffled, transcendent yearnings.

It was not that science was new. During the previous two centuries, much had been achieved in this realm. Now, however, it stood mostly alone at the pinnacle of secular obsessions and concerns.

And with the arrival of Jonah Salk’s “miraculous” discovery of 1953, this newly dominant scientific creed finally received its much awaited and much needed object of “eucharistic” passion, the widely and routinely distributed vaccine, around which elite culture planners would build new liturgies of solidarity, and in time, of ostracization, the latter needed to “establish the mark” against those who were unable or unwilling to believe in the transcendent powers of this injection and others like it.

The parallels between the religious and medical rituals are greater than they might at first appear. As in the taking of the Eucharist, the act of receiving a vaccine pierces the habitual physical barrier between an individual and the rest of society. And as with the Eucharist, one submits, or is submitted by others, to this momentary violation of corporal sovereignty in the name of engendering a fruitful solidarity with others.

In becoming vaccinated, as we were constantly told between January 2021 and the summer of 2023, we were engaging in an act of altruism that would not only enhance our own physical hardiness but that of the various communities of which we are a part.

And in order to add further muscle to this appeal to group solidarity, we were also constantly told that any failure to partake of this new social sacrament could and probably would damage not only our communities, but those we love the most, the members of our families.

Indeed, in a video aimed at their respective flocks, a group of prominent Latin American bishops—playing into the hands of those promoting the sacramental nature of the vaccines similar to the way that certain Italian clerics imbued Mussolini’s materialist cult of the nation with transcendental airs—all but explicitly drew a line of continuity between the solidarity-inducing waves of love that radiate from the act of taking the Eucharist and those set in motion by the taking of the vaccine.

Said one, “As we prepare for a better future as a global interconnected community we seek to spread hope, to all people, without exceptions. From North to South America, we support vaccinations for all.”

In a message which is designed to channel the believer’s infinite faith in the life-giving promise of the Eucharist toward the untested products of profit-making corporations already found guilty of multiple crimes, another said: “There is still much to learn about this virus. But one thing is sure. The authorized vaccines work, and they are here to save lives. They are key to the path of personal and universal healing.”

Still another stated that “I encourage you to act responsibly as members of the great human family, striving for and protecting integral health and universal vaccination.”

Not to be outdone in this game of cynically commingling of the sacred and the pharmaceutically profane, Pope Francis chimed in with the following: “Getting Vaccinated with the vaccines authorized by the relevant authorities is an act of love, and helping to ensure that the majority of people do so is also an act of love, for oneself, for our families and our friends and for peoples…Getting vaccinated is a simple but profound way of promoting the common good and caring for one another, especially the most vulnerable.”

Could the appropriation of sacramental language and sacramental thinking to justify the enactment of a wholly secular political program with evident hostility to the ideas of moral discernment and individual human dignity be made any clearer?

One of the more pernicious conceits of our age is the idea that by declaring oneself irreligious, one is immediately freed from the longings for transcendence that have fueled religious practice among humans since the beginning of our experience here on earth.

Those among our sign-making elites obsessed with exercising control over the masses know better. They know that such yearnings are deeply encoded in the human psyche.

And since the dawn of what Charles Taylor has called our Secular Age, they have exploited contemporary man’s blindness to his own subterranean desire for transcendence by supplying him with secular simulacra of traditional liturgical and sacramental practices that channel his energies toward projects that redound to the benefits of their fellow elites while weakening the strength of traditional forms of being and knowing.

Isn’t it about time that we caught on to the reality of this dangerous and grubby game of sacramental bait-and-switch?

-

Thomas Harrington, Senior Brownstone Scholar and Brownstone Fellow, is Professor Emeritus of Hispanic Studies at Trinity College in Hartford, CT, where he taught for 24 years. His research is on Iberian movements of national identity and contemporary Catalan culture. His essays are published at Words in The Pursuit of Light.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.