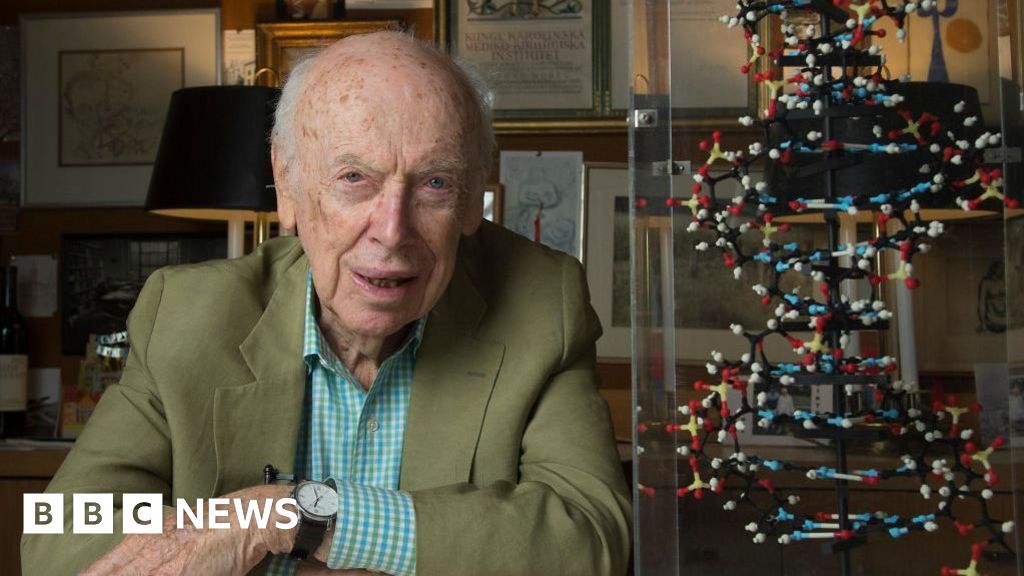

Obituary: James Watson

James Watson: Controversial discoverer of ‘the secret of life’

Getty Images

Getty Images

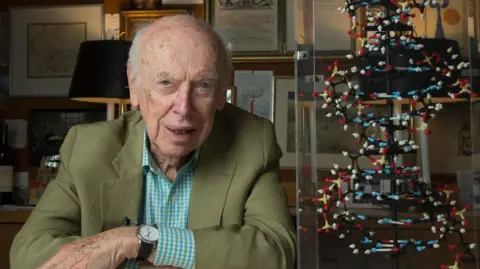

In February 1953, two men walked into a pub in Cambridge and announced they had found “the secret of life”. It was not an idle boast.

One was James Watson, an American biologist from the Cavendish laboratory; the other was his British research partner, Francis Crick.

Their discovery – of the structure and function of deoxyribonucleic acid or DNA – ranks alongside those of Mendel and Darwin in its significance to modern science.

The full Promethean power of their achievement would slowly emerge over decades of research by fellow geneticists.

It also opened a Pandora’s Box of controversial scientific and ethical issues – including human cloning, designer babies and “Frankenstein foods”.

Demonstrating that DNA has a three-dimensional, double-helix shape allowed Watson and Crick to unlock the secrets of how cells worked; the means by which characteristics were passed down through generations.

“When we saw the answer we had to pinch ourselves,” said Watson. “We realised it probably was true because it was so pretty.”

The discovery won them a Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1962 and a permanent place in the historic ranks of great scientific thinkers.

It also guaranteed that, if they said something controversial, it made headline news.

And Watson had plenty to say, most notoriously speculating about a link between race and intelligence.

Gonville & Caius College

Gonville & Caius College

When he first suggested that black people are less intelligent, London’s Science Museum cancelled a planned lecture – insisting Watson’s views went “beyond the point of acceptable debate”.

He suggested “when you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you’re not going to hire them”. And he wondered aloud if beauty not only could – but should – be genetically encouraged.

Watson was heavily criticised for saying that women should have the right to abort her unborn child if tests proved it would be homosexual.

He argued he was simply in favour of choice, that it would be equally permissible to favour homosexual offspring and that it was simply natural to want grandchildren.

He alienated many in his own profession, calling many fellow academics “dinosaurs”, “deadbeats”, “fossils” and “has-beens” in his autobiography, Avoid Boring People.

In 2014, he became the first living recipient of the Nobel Prize to auction off his medal – in part to help fund future scientific discovery. A Russian tycoon bought it for $4.8m (£3m) and promptly gave it back to him.

Early life

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on 6 April 1928 to a family who believed in “books, birds and the Democratic Party”.

He was the only son of Jean and James, who were descendants of English, Scottish and Irish settlers.

His political interest came from his mother who worked for the Democrats. The basement of their bungalow would be pressed into service as a polling station at election time.

His father’s passions were science and bird-watching. Young Watson would accompany his father on birding trips. He learned that science was a discipline demanding careful observation from nature.

Getty Images

Getty Images

This left no place for faith. Brought up a Catholic by his mother, Watson described himself as an “escapee from that religion”.

“The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father did not believe in God,” he said.

The Great Depression of the 1930s saw his father’s salary suddenly cut in half and a dash to the bank to get their remaining savings out in time.

Watson slept in a tiny attic room shared with his younger sister, Betty.

He was a skinny teenager told to go to buy milkshakes to “fatten him up”. He was socially awkward and expelled from school for poor grades – his work badly affected by a bout of scarlet fever.

“None of my classmates thought I would amount to much,” he recalled.

He did not think of himself as a precocious intellect but he took up a scholarship at the University of Chicago at the tender age of 15.

He put it down to “my mother knowing the dean of admissions”.

Intellectual flowering

University freed him from complicated social hierarchies of school life where popularity and physical stature were critical. It provided the environment where a brilliant but awkward teenager could thrive.

Watson thought of majoring in ornithology, the study of birds, but changed to genetics – influenced by Erwin Schrodinger’s book What is Life?

He described the University of Chicago as an “idyllic academic institution” where he was “instilled with the capacity for critical thought and an ethical compulsion not to suffer fools who impeded his search for truth”.

The prevailing scientific wisdom was that genes were proteins able to replicate themselves. The presence of DNA was dismissed as something “stupid” simply there to support the protein.

Watson became fascinated by the new technique of diffraction whereby X-rays were bounced off atoms to reveal their inner structures.

He became convinced that DNA had a structure of its own and was determined to find it. He thought the place to do that was England.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo Library

At Cambridge, he met Francis Crick, a physicist by training with “extraordinary conversational ability” and “the loudest laugh I have ever known”.

They began constructing large-scale models of possible structures for DNA and trying to fit them to the available evidence. In one of the biggest scientific controversies of all time, not all of this evidence was their own.

Watson and Crick were in a race with another team at King’s College London. Their rivals were Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. They got on well with him and appallingly badly with her.

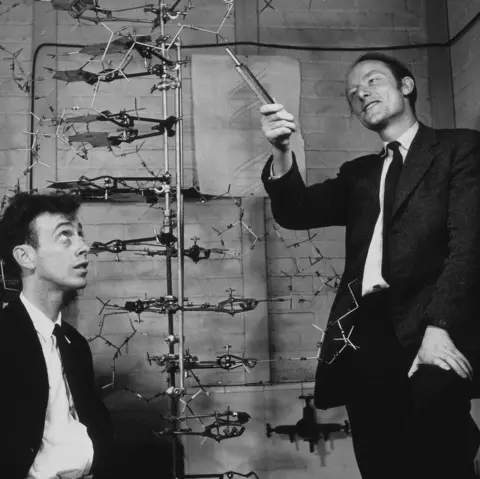

Rosalind Franklin

Wilkins corresponded with the Cambridge pair, sometimes exchanging his thoughts and insights.

But Franklin was different. She was the most experienced chemist and an expert in diffraction.

She, alongside her student Raymond Gosling, would take photographs of the patterns made by X-rays as they bounced off DNA molecules.

Watson and Crick found Franklin “hostile” and thought she jealously guarded her research and worked in isolation.

They were dismissive and sniped about her appearance, but Watson wasn’t above taking a look at her work when Wilkins offered. Franklin was not asked for her permission.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The key evidence was Photo 51.

It shows a fuzzy pattern of X-rays that fascinated the Cambridge pair. They threw themselves into a frenzy of model building, testing each theory against the new information.

From this, they deduced that DNA must have a three-dimensional, double-helix structure – like a twisted ladder with rungs formed of alternating salt and phosphate groups.

Their key conclusions were that, if separated, each strand provided a template for creating the other and that the order of the “rungs” was a code.

If you can understand that code, they reasoned, you can unpick the wonders of life.

Nobel Prize

Wilkins wrote to his rivals to congratulate them on winning what had, at times, been a bitter race.

When he was awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Medicine – alongside Watson and Crick – Franklin did not accompany them.

Her life was cut short by ovarian cancer at just 37.

According to the rules of the Nobel committee, only the living could be honoured. Her fans felt Franklin had been cheated twice.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Later Watson and his wife, Elizabeth, moved to Harvard. He became professor of biology and had two sons – one of whom suffered from schizophrenia.

Then he took over the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State – an ailing institution which he was credited with turning into one of the world’s foremost scientific research institutes.

In 1968, his account of the race to discover the structure of DNA, The Double Helix, was published.

It is a painful examination of the story. It rakes over the personalities, controversies and bitterness from his point of view. He considered calling the book Honest Jim.

But for all Professor Watson’s academic achievements, his later career was overshadowed by his controversial public statements.

In 1990, the journal Science wrote that “to many in the scientific community, Watson has long been something of a wild man, and his colleagues tend to hold their collective breath whenever he veers from the script”.

At a conference in 2000, Watson proved it right.

He floated the idea that black people might have larger libidos than whites. His lecture argued that melanin, which gives skin its colour, boosted the sex drive.

“That’s why you have Latin lovers,” he told the delegates. “You never have an English lover, only an English patient.”

He suggested that humanity might screen out the stupid people by genetic testing. Then he gave an interview that put the biggest dent in his reputation.

While promoting his autobiography, Watson spoke to the Sunday Times.

The piece quoted him as “gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really”.

Watson went on to admit this “hot potato” was difficult to address and his hope was that everyone was equal.

However, he said, “People who have to deal with black employees find this not true”.

He later apologised but his research institute stripped him of executive power and kicked him upstairs as chancellor emeritus.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo Library

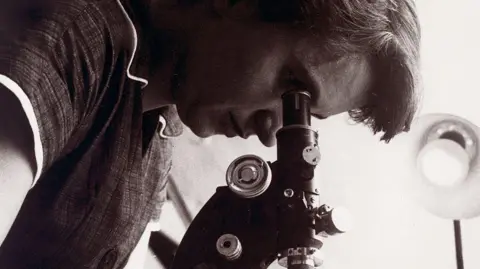

James Watson spent the rest of his life continuing to raise money for medical research, often shamelessly reaching for the heart strings.

“Nothing attracts money like a quest for the cure to a terrible disease,” he said.

He never stopped causing waves, warning that “Viagra is fighting evolution”.

Men, he also argued, should store sperm in their teens to avoid an increased possibility of fathering children with developmental difficulties.

He repeated his views on the link between race and intelligence in a 2019 documentary, after which the scientific community revoked his remaining honorary positions.

He will be remembered as the “Godfather of DNA”, the man who unravelled the secrets of life, and a world-class controversialist who often put his foot in his mouth.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.