How a fertility gap is fuelling the rise of one-child families

Hazel ShearingEducation correspondent

BBC

BBC

Natalie Johnston was scrolling on Facebook a couple of years ago, when she came across a group called, “One And Done On The Fence”. Seeing it, she felt a sense of relief.

“It was nice to hear someone giving it a name,” she says.

She and her husband have a five-year-old daughter called Joanie but they knew they probably wouldn’t have a second child – not because they couldn’t, but not out of choice, either: Natalie finds it hard to imagine having the time and money for one.

“You know you’d love that baby, everyone tells you, but there’s a little teeny niggle where you think, ‘what if I put my first in that position where she can’t do the activity she wants to do because I’ve got to spread money out between two’?”

She adds: “Is it okay to say you’re only having one because they don’t fit into modern ways of parenting?”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Modern parenting, for Natalie, 35, looks like family holidays with Joanie. It looks like weekday evenings hearing about her day at school and helping her with homework. But, with demanding jobs and no family living nearby to help with childcare, it also looks like an expensive childcare jigsaw.

But ultimately, deciding whether or not to have a second is a tough decision. “I think you worry you’d regret it,” she says.

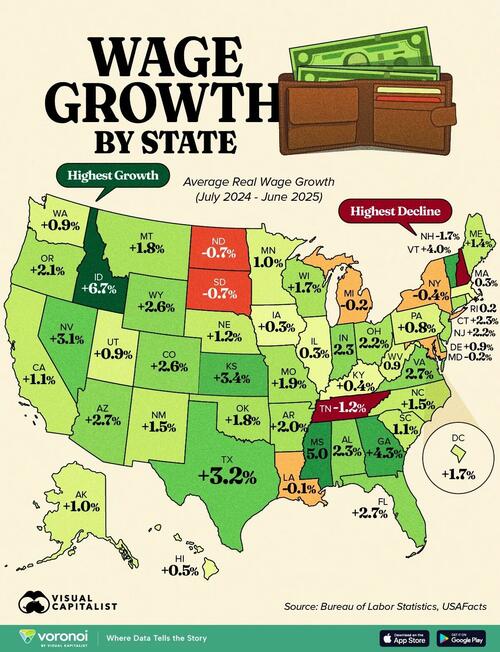

The fertility rate was 1.41 children per woman in England and Wales last year, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – the lowest on record for a third year running.

And the proportion of families with one child has grown since the turn of the century.

They made up 44% of all families with dependent children in England and Wales last year, up from 42% in 2000. (Though the peak was 47% in the early 2010s, which then dipped before picking up again after Covid.)

The UK’s falling birth rate is part of what the United Nations calls a “global fertility slump”, which it puts down, in part, to money worries.

People aren’t “turning their backs on parenthood”, says the UN in a summary of its Population Fund’s State of World Population report, which surveyed people across 14 countries.

Instead it says they “are being denied the freedom to start families due to skyrocketing living costs, persistent gender inequality and deepening uncertainty about the future”.

Bridging the ‘fertility gap’

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said earlier this year that she wants “more young people to have children, if they so choose”.

She pointed to the expansion of funded childcare hours in England as a way the government was trying to recover “dashed dreams”.

Annual nursery costs for a child under two in England did fall this year for the first time in 15 years, according to the children’s charity Coram. They are now an average of £12,425, down 22% on the previous year. However they are slightly up in Scotland and Wales, at £12,468 and £15,038 respectively.

A study from University College London (UCL) last year suggested two-fifths of 32-year-olds in England want children – or more children, if they are already parents – but only one in four of them are actively trying to conceive.

Dr Paula Sheppard, an anthropologist at the University of Oxford, believes parents in the West still think of having two children as “the norm”.

However, she says there is a “fertility gap” and that “for every three kids wanted… only two are born”.

“A lot of this gap is driven by… people starting families later and later in life,” she explains – often a result of education and career opportunities for women and changing gender roles.

“It becomes a whole lot more difficult to get pregnant [and] it becomes a whole lot more difficult to keep the pregnancy.”

Fewer pupils, less cash for schools

The falling birthrate is giving education policymakers a headache.

The number of pupils in England has dropped by 150,000 since 2019, and will fall by a further 400,000 by the end of the decade, according to the Education Policy Institute.

Schools are given money per pupil, so fewer pupils means less cash. Less cash, in turn, is an issue for those head teachers struggling to fund staffing and resources.

Getty Images

Getty Images

About a year ago, a post on a UK Reddit thread for teachers raised what one contributor saw as another potential impact of more only children on the education system.

The contributor wrote that they had seen a rise in “spoilt” children with “demanding behaviour due to overindulgent parenting”. These children tended to have siblings who were much older or no siblings at all, they claimed.

The idea that children without siblings may be selfish or spoiled dates back to research conducted in the late 19th century by psychologists G Stanley Hall and E W Bohannon.

“Selfishness is one of the most striking traits of the only children in families,” they wrote in their Study of Peculiar and Exceptional Children. “‘The only child’ is deficient on the social side.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

But more recent studies have debunked that idea.

“Numerous studies have disproven these myths that only children are maladjusted, spoiled, and lonely,” explains Dr Adriean Mancillas, a psychologist and professor in California State University’s education department.

Only children and academic performance

Dr Mancillas has spent her career exploring family dynamics, the development of only children, and mental health intervention in schools – and says most research “consistently demonstrates advantages of being an only child, particularly in educational and academic outcomes”.

This is down, mainly, to a theory called “resource dilution”. In simple terms, she says this means parents with one child “are able to be more involved in their child’s education”.

“Children with siblings share in parents’ time, emotional support, attention, and financial resources whereas the only child does not,” says Dr Mancillas. “This singular focus of resources tends to provide academic advantages for the only child.”

She points to some research that suggests many only children did better academically when schools closed to most pupils in lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic, “because of the relative availability of parental resources”.

Getty Images

Getty Images

“Resource dilution” is one of three social science theories about the consequences of being an only child, according to University College London (UCL) academics.

The second is “confluence theory”, which also suggests that only children perform better than children with siblings academically because a family’s “intellectual environment” declines as the number of children grows.

Then there is “socialisation theory” which, in contrast, argues that siblings help children learn how to share, negotiate and resolve conflict.

Existing research, according to the UCL academics, support the first two theories. But, like Dr Mancillas, they say it “generally does not support the socialisation theory as it finds that only children are comparable to children with siblings (especially those with few siblings) in terms of personality, parent-child relationships, achievement, motivation and personal adjustment”.

Dr Mancillas suggests there could be something else feeding into only children’s better academic performance, too.

“Studies show that parents with one child tend to have attained higher educational outcomes themselves than parents of multiple children,” she says.

“Much of the time, parents have delayed having children in order to complete career or higher educational goals. This would suggest that parents who have one child likely place a high value on education overall.”

‘Little emperors’ and ‘one-child dynasties’

Earlier this year, Susan Newman, an American psychologist explored so-called only-child dynasties – where parents who are only-children, have one child themselves – in an article to accompany her new book, Just One: The New Science, Secrets & Joy of Parenting an Only Child.

One of the most surprising findings from the new research for her book was, she wrote: “Adult only-children are increasingly choosing to have “just one” child themselves.

“The resulting only-child dynasties underscore the trend. Count on seeing more of them, most noticeably without the spoiled, entitled ‘little emperors’ we heard so much about for so long -despite a lack of evidence to support such misinformed stereotypes.”

The phrase has been used as shorthand to describe the only children born under China’s one-child policy, the idea held by some being that it led to a generation of “solitary children pampered and paraded with a retinue of parents and elders”.

Getty Images

Getty Images

However, while the policy did leave a lasting legacy after its end in 2015 – an ageing population, for example, and a gender imbalance because of a traditional preference for male children – research has suggested that the “little emperor effect” has not been a part of it.

There were “very few only-child effects” on children’s personality, according to a study of Chinese schoolchildren carried out by American researchers at two Texas Universities.

‘People feel very alone in this’

The phrase “one and done” was only just beginning to emerge when New York-based journalist Lauren Sandler began writing her 2013 book, One and Only: The Freedom of Having an Only Child, and the Joy of Being One.

“I would be on the subway with my adorable child and someone would say, ‘so cute, when are you having another one?’

“There is so little discussion about what it means to have single children, which is incredible to me considering how many there are.”

She adds: “I think that people feel very alone in this.”

She began to question why some people assumed she would want more children, something she also explored for her work. It used to be that having larger families was how we survived, she points out.

“A family was a workforce, and that was very much a necessity until the industrial revolution.”

Only after the industrial revolution, and the introduction of child labour and welfare laws did that change. “The opportunity costs and the economic costs of children shifted dramatically,” she explains.

Getty Images

Getty Images

She also questioned the negative connotations that can sometimes be associated with having one child.

“There’s also a lot of research that shows that only children do not take relationships for granted at a very, very young age. So, [it’s not the same as when you] fight with your older brother and then just, through exposure, need to make up again.

“These people aren’t going to be at the dinner table with you every night. Because of that, there’s a lot of care that seems to come into relationships. And so that is sort of the opposite of the selfish stereotype of only children.”

Trump and the $5,000 ‘baby bonus’

So teachers may not really have a generation of “little emperors” on their hands. But the impact of the falling birth rate is still very much being felt by some schools, and more widely too.

Policymakers, for example, are grappling with the impact of the UK’s ageing population on public services, taxes, and the growing cost of state pensions.

“Falling birth rates and an ageing population can create pressures on public services and public finances because the balance between the number of people working and the number of people drawing on age-related services changes over time,” says Dr Alina Pelikh of University College London, who specialises in demography.

“Governments may need to consider adjustments – whether through pension age, contributions, or other measures – to ensure long-term sustainability.”

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

The concerns are global, and governments around the world are trying to encourage people to have more children.

US President Donald Trump has mentioned the idea of a $5,000 “baby bonus”. Poland has just introduced a policy of zero personal income tax for families with two or more children. And in Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orban has introduced tax exemptions for mothers.

But for all the the statistics and policymaking this is, ultimately, a very personal decision.

Natalie couldn’t be prouder of her daughter, who has recently been made “values ambassador” in her class, encouraging other children to show empathy and respect.

“She has been chosen, not because she’s an only child, because they don’t know whether she’s got siblings or not. She’s been chosen based on her personality,” says Natalie.

“I don’t think I was ever worried about not giving her [a sibling], because you can never have a child for somebody else.

“You’ve got to have a child for yourself, haven’t you?”

Lead image: Getty Images (stock picture of a child)

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.