Embracing Ambiguity and Outliers in a VUCA World

We, especially those engaged in the health professions, need to stop the relentless attempts to normalize all data to fit the nice bell-shaped distribution that we assume is how the world works. Sometimes it does, but sometimes it doesn’t. We need to understand the words “It depends.”

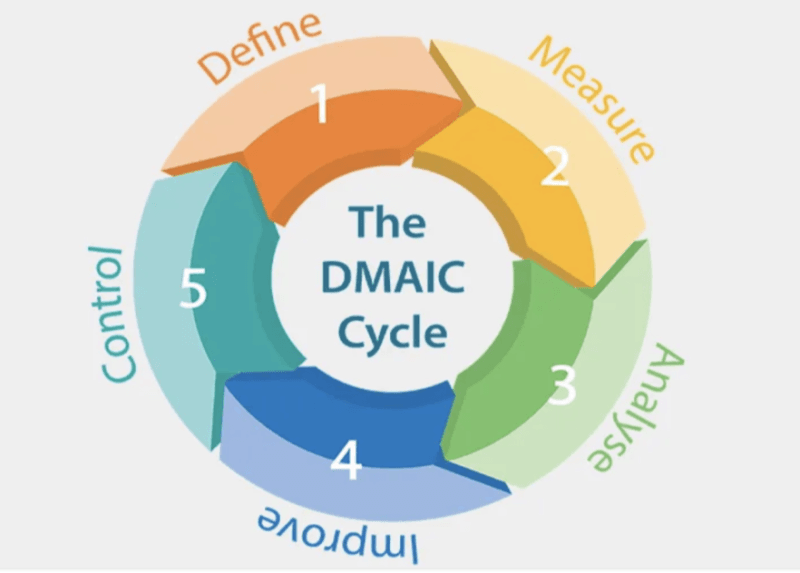

Two decades ago, I was a Six Sigma Blackbelt deeply immersed in the applications of statistical quality control to healthcare. Our efforts were primarily focused on the process, and as such, the way to improve the outcomes depended entirely on optimizing the processes of care. Our work was organized around the “DMAIC” wheel:

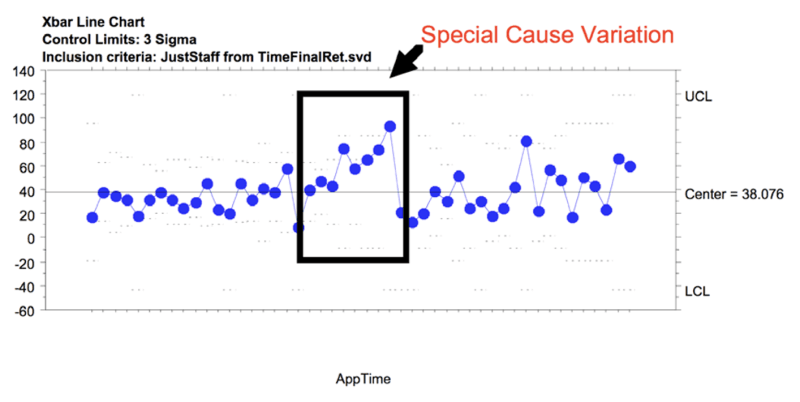

We would Define the problem and the process to improve it, Measure the process, Analyze it, take actions to Improve the process, and then make sure we could Control it. The Control would take the form of specialized charts that showed variation in our measures, such as this one on patient waiting time versus time of appointment:

There would be variation in any process, split into the normal random common cause variation (such as the background up and down motion of the data points around the center line) and special cause variation (like the points in the box). Voila! Masterful! It took a chart to show that patient wait time increased over the lunch hour!

I don’t mean to be too sarcastic. There were many instances in which statistical process control led to significant improvements in patient care. For instance, we were able to reduce the time it took for a patient with chest pain from a blocked coronary artery to reach the Cath lab from 2 hours to 32 minutes. The problem came when we thought that everything could be improved this way.

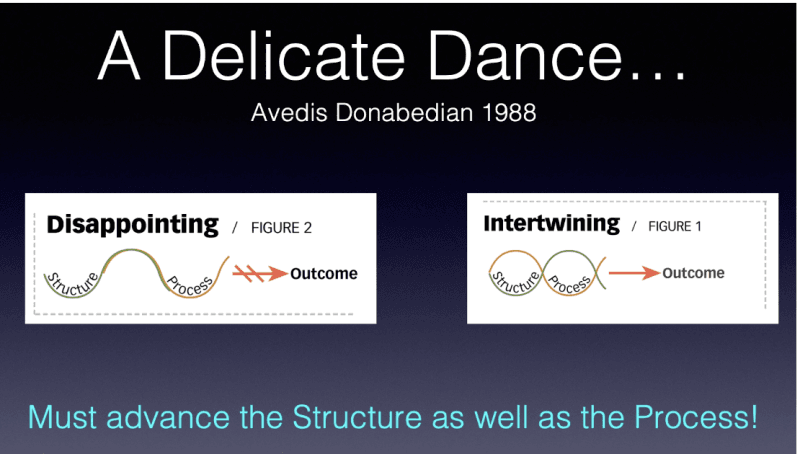

Fresh from this success with the coronary blockage, we attempted to use the same techniques to reduce the time from abnormal mammogram to biopsy. When we started, that time was measured in weeks! Imagine the stress caused to the patient! We were able to get it down to 4 days…but the effort destroyed everything else in the pathology department, as we didn’t have the structure to support the process. More than a half-century ago, Avedis Donabedian understood that Outcome depends on a delicate dance between process and structure:

The structure that supports a process is more than bricks, mortar, and machines. It includes the intellectual capital of the professionals caring for the patient, the expectations and emotional state of the patient, the family structure, even the climate! This is the fallacy of believing that importing “best” practices will be the answer. The “best practices” of the Mayo Clinic work because of the interactions of all these elements. It works well at the Mayo Clinic, but may, and often doesn’t, work at other places. Indeed, even the Mayo Clinic recognizes that nuances of varying community needs must alter their care processes. What needs to be done is to use Critical Thinking skills to discover the “best practice” for the unique makeup of patients, professionals, and the system for each location.

We have empiric reasons to prove this is a viable approach. In 1990, Marian Zeitlin, Hossein Ghassemi, and Mohamed Mansour published Positive Deviance in Child Nutrition. A year later, Zeitlin followed this with a journal publication on the same topic. Both the book and the journal article noted that in impoverished countries, some children seemed to flourish (Positive Deviants) while others in the same situation did not. The authors discovered that simple, sometimes overlooked factors such as supplementation with locally available nontraditional but high-quality foods, social interaction, and praise played monumental roles in achieving success.

By identifying these Positive Deviants and understanding what made them stand out, the differences could be applied to the larger population, with significant improvement. Importantly, these differences would only be applicable to individuals in the same micro-environment. It was the interaction of the system and the agents so central to the working of a Complex Adaptive System that produced the success.

Working in Vietnam at the same time, Jerry and Monique Sternin embraced this Positive Deviance methodology with equally impressive results. Even more notable, they transferred the technique of identifying Positive Deviants outside of the study of nutrition to the successful reduction of Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt.

These researchers did not “import best practices” from outside but worked to “accentuate the positive” within their specific environment. In Complexity Science language, they augmented positive attractors and dampened negative ones! They did this by working from the inside out. As Jerry Sternin was quoted in a 2010 FastCompany article:

Maybe, says Jerry Sternin, the problem isn’t with the outside experts or with the company. “The traditional model for social and organizational change doesn’t work,” says Sternin, 62. “It never has. You can’t bring permanent solutions in from outside.” Maybe the problem is with the whole model for how change can actually happen. Maybe the problem is that you can’t import change from the outside in. Instead, you have to find small, successful but “deviant” practices that are already working in the organization and amplify them. Maybe, just maybe, the answer is already alive in the organization — and change comes when you find it.

Such an approach was used in multiple studies showing a significant reduction in hospital-acquired MRSA (Methicillin Resistant Staph Aureus) infections. One would have thought that such a methodology would spread rapidly, as it seems so rational and has a proven track record. It has spread, albeit in limited but extraordinarily effective instances.

In 1982, the Southcentral Foundation in Alaska took over the responsibility from the Indian Health Services for management of the healthcare for 70,000 Native Alaskan and American Indians in the Anchorage Service Unit. The leaders correctly understood the message of Jerry Sternin and over the ensuing decades developed one of the most successful healthcare organizations in North America, or the world for that matter. Their NUKA System of Care won not one, but two, coveted Baldrige Awards for quality. The visionary leaders understood that much of health and healthcare is a Complex Adaptive System that responds to emergent rather than imposed order.

The Southcentral Foundation mirrored the same approach as the Jönköping Health System in Sweden. Under the leadership of Göran Hendriks (not a physician, but a world class basketball coach), Jönköping Health System developed a true learning organization focused on high quality healthcare.

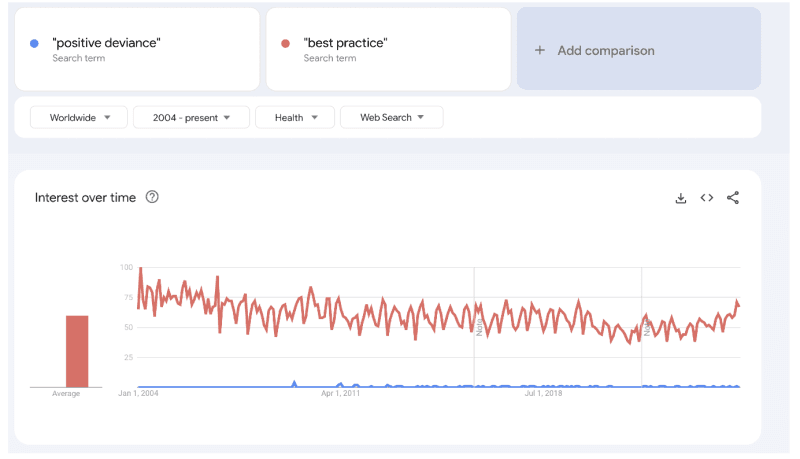

It would have been a reasonable expectation that the concrete, objective experiences of these people and organizations would have ignited a fire of enthusiasm for duplicating their results. Unfortunately, that has not been the experience. Examine these results from Google Trends for the search terms “Positive Deviance” and “Best Practice:”

Note that the bottom blue line (representing “Positive Deviance”) hardly registers compared to the red line (representing “Best Practice”) in the Worldwide “health” searches from 2004 to the present.

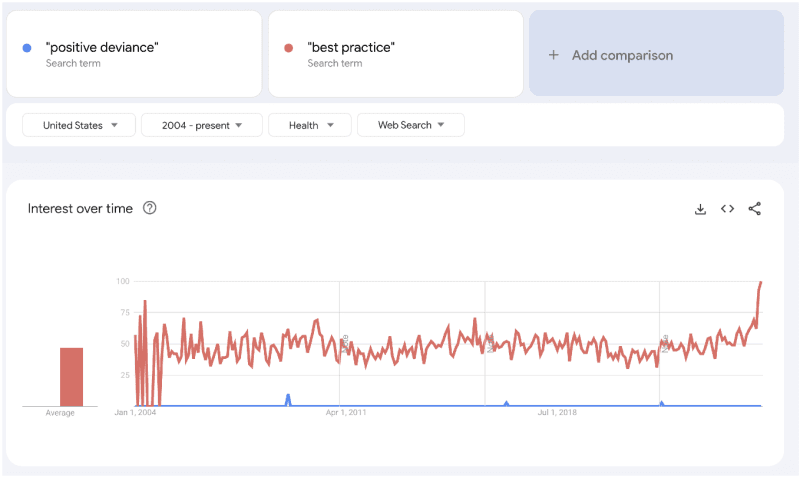

Even more astounding is an identical search limiting inquiries from the United States:

Why is that? There may be multiple plausible reasons, but the one that jumps out has to do with the way modern medicine has become uncomfortable with ambiguity and outliers. Understanding those elements is difficult. It necessitates a deep dive into the problem and the data. Instead of a definite and singular “yes” or no” the correct answer may be “It depends.” Sometimes the answer may be yes, sometimes no, depending upon the conditions.

It is critical to understand the difference between problems that are simple, merely complicated, truly complex, and chaotic. All such elements may be present, sometimes even mixed together! A complete discussion of the differences and the approach is beyond the scope of this essay, but I would refer the reader to A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making in the Harvard Business Review by David Snowden and Mary Boone. Even viewing the three-minute video on the subject would convey a kernel of understanding.

Unfortunately, the most expedient course would be to assume everything is simple, outsource critical thinking, and rely upon protocols. Protocols disregard the individual and treat the herd. The messy outliers can then be ignored.

There is perceived safety in protocols. If one does what most of one’s peers are doing, it is easier to hide if there should be a negative outcome. Perhaps this is an expected action. Daniel Kahneman shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics with Vernon Smith for his seminal work with Amos Tversky on Prospect Theory. Most people exhibit risk aversion. Greater disappointment is experienced when losing $100 than satisfaction is felt when gaining $100.

Additionally, more work is required and more emotional energy expended in attempting to venture beyond protocols to deliver the optimum care to individual patients. It takes time, and time is a commodity that has become in short supply for most physicians. The increase in physician burnout is correlated with the increase in time demanded for non-patient care, such as filling out forms and completing the all-important Electronic Medical Record.

Justifying a lapse in protocol is yet another burden and may have far-reaching employment consequences. Viewing reruns of House is bittersweet. The character portrayed by Hugh Laurie “using a crack team of doctors and his wits, an antisocial maverick doctor specializing in diagnostic medicine does whatever it takes to solve puzzling cases that come his way” wouldn’t last a week in today’s world of corporate medicine. Of no consequence is the fact that they solve the problem. The solution is secondary; the process is primary.

Almost 20 years ago, Abraham Verghese described a troubling observation: Culture Shock — Patient as Icon, Icon as Patient. The real object of the physician’s attention was the production of the medical record. The actual patient as a human being was relatively unimportant. This frightening reality seems to have only intensified. The patients don’t like this. The physicians don’t like this. But those controlling medicine now, the administrators, seem to like it a lot.

As a worrisome extension of this mindset, there are some who envision AI replacing or at least significantly augmenting the work of physicians. Certainly, AI holds promise for pattern recognition in radiology and pathology. However, the burgeoning rise in use of AI by physicians may also be a manifestation of risk-averse behavior. This could be ominous, as there remains significant doubt that AI can be trusted to make ethical decisions without human oversight. Even more troublesome is the intentional lying by some AI platforms. Could it be that AI has learned to “fake it” if they don’t know the answer?

Even in the best-case scenario, there is danger in protocols and AI-derived plans. Strict adherence to these protocols and plans will deprive at least some people of optimum care. There are outliers (positive and negative) in response to all medicines and treatments. If a physician’s primary duty is to the herd and population and not the individual, ignoring the needs of the outliers is just shrugged off as “collateral damage” for the “greater good.” One only has to look at the experience in Covid to see the tremendous harm done under those circumstances.

We did not arrive here overnight. The genesis of this began 25 years ago under the euphemism of “cost-effective” care. It may have been cost-effective, but it just as easily could have meant that the physician did not seek an alternative with enough diligence or interest. For example, pharmacogenetic studies have been available for years and can confirm that the correct drug and dosage are chosen for individuals. Yet the use of these studies is limited, primarily because of the cost-effectiveness question and lack of education on the part of prescribers.

In the Pre-Covid era, there was a move towards what was called “Precision Medicine,” where it was recognized that optimum care often demanded individualized treatment plans. Precision medicine was effectively terminated with the massive standardization and mandates under Covid. It remains to be seen if it will be resurrected.

In addition, in a strict adherence to a protocol based on past performance or an AI regiment developed through a training set, positive deviants go unrecognized. Progress is limited to what worked in the past and innovation is stifled.

There is a high price that physicians, nurses, and all health care professionals pay in outsourcing their critical thinking. However, it pales in comparison to the price paid by the patients themselves. If organized medicine cannot or will not institute constructive adaptation and renounce the past compliance with rules seemingly designed to benefit Big Pharma or other extraneous stakeholders in the physician/patient relationship, society and individuals must take control of their own destiny and bring the pressure necessary for improvement.

Far from things to be avoided, variation, ambiguity, and outliers are the keys to innovation and optimal clinical care:

In much of what we do, some degree of variability, including variability in measurement, is unavoidable. In addition to variability in measurement, we have variability in surgeon experience, variability in patient physiology, variability in the inflammatory response, etc. As much as we may wish otherwise, we need to understand variability and not think the only answer is to reduce it. Our approach should not be to build a system so robust it will never fail, but to construct a system that is resilient enough to recognize failure early and take the necessary steps to correct course.

Similar to leaders in business, those in both Academic and Clinical Medicine must embrace variation, ambiguity, and outliers as opportunities and not ignore them or keep insisting that they be neutralized

In short, medicine must learn to operate in a VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity) world, just as business has. The recognition of the importance of this is beginning, but it must be more widely disseminated and added to the clinical competencies at every step in the education of health professionals. Only then will health professionals stop trying to minimize variation and ambiguity. We can’t just ignore them and pretend they don’t exist. We must see them for the potential opportunities they present.

Imagine if leaders in Public Health, Academic Medicine, and Medical Organizations would have understood these concepts during the dark days of the Great Covid Disaster. Unfortunately, they did not. Even now, the medical establishment has not realized its folly and the high price society continues to pay for its willful blindness. Witness David Bell’s recent excellent essay on Brownstone, The American Academy of Pediatrics: Mining Children for Profit.

Mankind deserves better than this!

-

Russ S. Gonnering is Adjunct Professor of Ophthalmology, Medical College of Wisconsin.