Don’t Bail out Soybeans

Question: What does a business do when nobody wants its product or services?

Answer: It asks for the federal government to bail it out and pay for a product nobody wants.

If this sounds silly to you, consider what’s going on with America’s soybean farmers who lost a quarter of their market when China decided to switch sourcing to Brazil and Argentina in the last couple of months. As a farmer myself, my heart breaks for the plummeting prices and the prospect of losing $200 per acre on the 2025 crop.

But on the other side of my breaking heart is a desire to hear any soybean farmer say, “I’m going to grow something profitable.” You’d think in a capitalistic society someone raising soybeans would recognize simple principles in supply and demand. You can’t keep supplying when demand wanes and expect a sugar daddy to subsidize your bank account.

What kind of economic gymnastics makes soybean farmers think they deserve taxpayer subsidies for a commodity in oversupply? Where is the courageous soybean farmer who dares to pivot to something else? Or who dares to suggest the farmer can solve this conundrum without government interference?

I’m well aware that the current crisis is China’s retaliation for President Donald Trump’s tariff campaign. Farmers can rightly say, “We didn’t see this coming and planted based on credible market expectations and we were blindsided.” But how many times has this cycle, or something like it, repeated itself in the last 50 years? How many of these debacles does it take to convince someone that a fundamental change is necessary?

But it’s crickets in the soybean industry. “Build us biodiesel facilities. Find other markets. Give us billions in subsidies.” The refrain is loud—and painful to hear. Farmers have historically been some of the most can-do resilient people in society. But right now these soybean farmers sound like a bunch of whining babies.

How did we get here? How did we turn the rugged American farmer into a government dependent? In short, the farm bill and farm programs supposedly instituted to protect farmers from price fluctuations. The result is such that market intervention has led crop farmers growing the six special-interest commodities to stop thinking like businesspeople and instead think like entitled dependents.

The six crops are soybeans, corn, sugar cane, wheat, rice, and cotton. Nothing else gets subsidy anointing from the federal temple like these six commodities. The result is an unholy legacy jerking farmers from one promised salvation to another, none of which actually ends in a better trajectory for primary producers.

When I talk with these farmers about doing something different, such as converting their cropland to perennial prairie polycultures producing grass-finished and fattened beef with management-intensive bio-mimicry, their eyes glaze over as if I’ve invited them to join me on an exploratory rocket ship to Pluto. For the average person, appreciating the damage from farm programs is difficult.

When decisions run through a matrix of paperwork and farm program payments, it jaundices every option. The idea of getting along on your own without a government paycheck, without a program security blanket, is so foreign that it can’t find a home in the farm’s business plan. Worse than the financial dependency these programs create is the emotional straitjacket it wraps around farmers.

Right now, the United States has the smallest beef herd since 1950 and prices are unprecedentedly high. Today, cows are like four-legged gold bars. The beef herd reduction began in earnest during the drought in southern tier states during the 2021–2023 seasons. I met Mississippi farmers who went out to check their cows, only to find one or two with broken legs after stepping into wide cracks in the soil. Unbelievable. Tragic.

Farmers liquidated their herds during that time. Unlike soybeans, you can’t just plant more cows when the rains return. And return they did in 2024 and 2025. These same parched acres are now exploding in grass without enough cows to eat it. Expanding a cow herd takes time. Since the average beef cattle operator is more than 60 years old, many don’t want to expand at any price. The successional conundrum is another story for another column.

Once a farmer makes a decision to expand, he has to save a heifer (female) calf and not send it to processing. That creates an additional shortage of beef going into market finishing channels. That heifer needs to be at least a year old before it’s bred to produce a calf 9.5 months later. When that calf hits the ground, it’s nearly two years after the initial decision to expand the herd. That calf then needs to grow for two years before it’s ready to be processed for the retail market. Add it up and it’s a four-year cycle. That’s not soybeans.

But that long cycle creates its own protections. It can’t whipsaw like an annual crop, and therein lies market stability. Perennials such as orchards and blackberries are similar. A farmer simply can’t jump on market fluctuations, such as rising prices, as fast with plants and animals that have a longer cycle than annual crops.

Note that all six commodities in the USDA subsidy sanctuary are annuals. Why? Because historically peer-dependent fraternally-minded farmers overplanted when prices rose and collapsed the market—all in one year.

The incoherence of the government negotiating trade deals for beef cattle with the United Kingdom and Australia when our domestic supply is shorter than ever in history is unfathomable. As if adding insult to injury, the government is thinking about giving soybean farmers billions of dollars when we’re oversupplied. Let’s get this straight. We need to export beef, which is in short supply. We need to subsidize soybeans, which are in oversupply. Does this make sense to anyone?

I suggest we eliminate all subsidies and all federal government salespeople. Let the market go where it will and let farmers learn to think independently, like businesspeople. How do we incentivize better decisions? By making people responsible for the consequences of their own decisions. Not by bailing them out when they make bad decisions.

Soybean farmers, I love you. But please stop. Sell the combine and chemical equipment and reinstall the fences you ripped out in the 1980s. Remember “Plant fencerow to fencerow?” The diversified, less dependent farm had fences.

No more. They’re all gone as subsidized crop farmers bow to the mono-cropped, chemical-dependent industrial system. Nursing at the government teat will never bring you independence or satisfaction. I challenge you to rip up the subsidy paperwork and wean yourself. You can do it.

Reprinted from Epoch Times

-

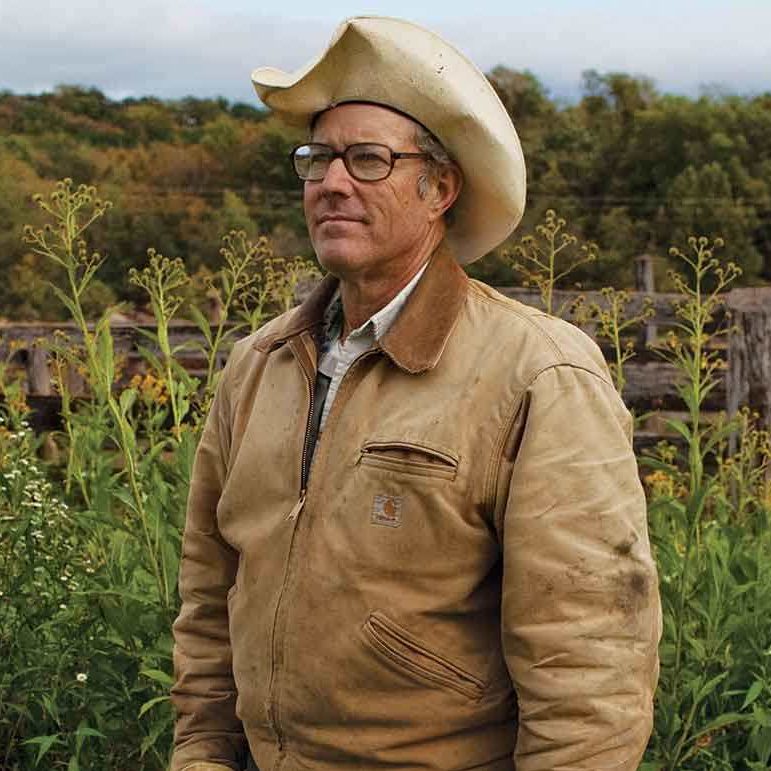

Joel F. Salatin is an American farmer, lecturer, and author. Salatin raises livestock on his Polyface Farm in Swoope, Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley. Meat from the farm is sold by direct marketing to consumers and restaurants.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.