The Covid Re-Review Project: All Models Are Wrong, and Some Are Dangerous

I welcome Eyal Shahar’s call for a re-review of Covid vaccine papers. In fact, I started long before Eyal blew the whistle — even before the vaccines appeared.

At the end of the terrible year 2020, a highly influential paper appeared in Science. It made headlines in major media outlets around the world. The paper, titled “Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19,” was soon used by governments across the globe to justify their increasingly authoritarian policies.

It attracted my attention because the last author was Czech mathematician Jan Kulveit. Together with my two colleagues, Ondřej Vencálek and Jakub Dostál, we wrote the following response:

“All models are wrong, but some are useful“ goes a famous saying usually attributed to George Box. Today, he would perhaps say that all models are wrong, and some are even dangerous. This, in our opinion, is the case for the study “Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19”1 that appeared in Science and received widespread attention around the world.

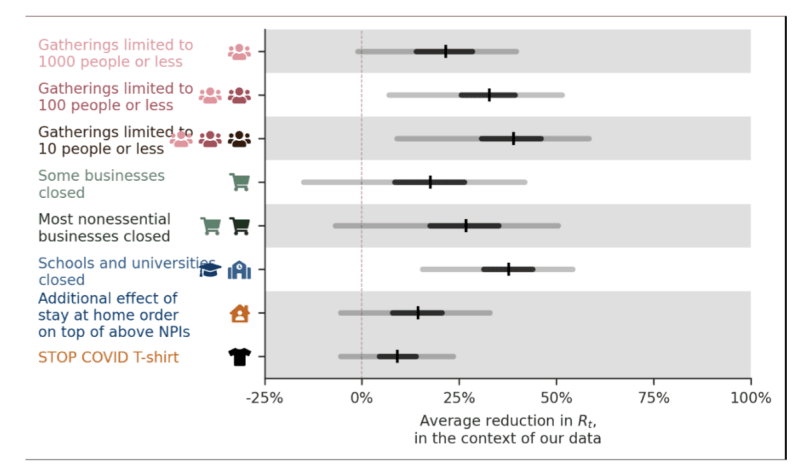

The study aims at understanding the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) in controlling the Covid-19 pandemic. The authors analyze data on the total case counts and death counts from 41 (mostly European) countries between January and the end of May 2020. They produce an estimate of the effects of 8 different NPIs (such as limiting gatherings of people, closing schools, etc.) which were implemented in many countries during the studied period. The effect of each NPI is quantified by the reduction in the infection reproduction number R at the time of the NPI imposition in the respective country.

The results have been widely welcomed because they seem to show that all of the NPIs generally work, and the effect sizes seem to agree with the common sense (e.g. the more you restrict gatherings, the greater reduction of R you obtain). Governments across the world will be very happy to hear that the restrictions they imposed were justified. But were they?

In fact, we do not know, and this study does not help us to find out. We argue that there is a fatal flaw in the model which renders it useless. Looking at the only equation in the body of the paper (see the “Short model description” section), we see that the authors assume the underlying (unobservable) basic reproduction number R0,c to be constant in time for each country. This basic reproduction number is then multiplied by the effects of the NPIs and this is fitted to data. Thus, the model assumes that any change in the dynamic of the epidemic is due to the NPIs. This is deceptive because it is circular. If you want to quantify the effects of an intervention, you cannot assume that all the observed effects are due to the very intervention.

Also, this assumption of constant R0,c suggests why the authors chose to stop modeling once any NPI is lifted. The NPIs are usually lifted as the epidemic dwindles. Thus, the NPIs are present when R is high, and they are absent when R is low. With data from a longer time interval (including the summer period of low prevalence and relaxed NPIs), the simple model the authors used would learn a negative effect – that NPIs speed up the epidemic. This was clearly undesirable, so the authors chose not to use the data from the summer to fit the model. Such modeling strategy is highly questionable.

To make our point completely clear, we performed the following experiment. We took the original dataset2 and invented a new NPI that never existed. Let us say that from the imposition of this new NPI on, each citizen was required to wear a T-shirt with a “Stop-Covid” inscription, until this NPI was lifted.

We drew a random date uniformly from the period over which a particular country was modeled, and “imposed” this T-shirt NPI on the data (see reference [3] for the original dataset with the T-shirt NPI added). We did not change the numbers of cases and deaths anyhow. Such an NPI never existed and so it could not have had any effect. We then ran the original model (see reference [4] for the link to GitHub to the version we used) without touching any parameters. The result is shown in Figure 1. The T-shirts almost made the pandemic go away!

How is this possible? Every epidemic has its intrinsic dynamics. The simplest SIR model produces a single peak in the number of active cases. If we want to reproduce such a peak with a simple exponential function (which is what the authors do), the coefficient in the exponent (i.e. the empirical reproduction number) must decrease in time from the beginning of the first wave. Thus, assuming that any effect on the reproduction number is due to NPIs, the model cannot produce anything other than assign a positive effect (i.e. a reduction in R) to any NPI. Even to a nonexistent one, as we have shown.

Thus, in our view the model is deceptive and very dangerous, because it can be used by the governments to retrospectively justify any NPI they chose to impose on the people. We do not claim that some/all of the NPIs have not had a positive effect. We only say that this model is no way to find out.

We sent our response as a letter to the editor of Science. The reply came back: they were very sorry, but they could not publish our letter. They did not say why.

So I copied and pasted their own “mission statement” into an email — something along the lines of “The Science family of journals furthers the AAAS goal to enhance communication among scientists, engineers, and the public.” I reminded them that no communication has ever been enhanced by censoring dissenting voices.

Eventually, they graciously allowed us to post our response as an e-letter, hidden behind the supplementary material of the original article. The e-letter cannot be cited, does not allow figures, and will not appear in any search.

We published a Czech version of our response under the title “Do the pandemic containment measures work? Yes, Minister!” on the website of the Czech Statistical Society. It earned us an oh-so-polite letter from the author — and a quiet ban in the mainstream media.

So that’s that. Got any better Covid review stories?

References

- J. M. Brauner et al., Science, 10.1126/science.abd9338 (2020).

- https://github.com/epidemics/COVIDNPIs/blob/1.3.6/merged_data/data_final_nov.csv

- https://gist.github.com/DostalJ/92e134f9ab4032289b77172d0e6ff583

- https://github.com/epidemics/COVIDNPIs/blob/1.3.6/notebooks/main_results.ipynb

-

Tomas Fürst teaches applied mathematics at Palacky University, Czech Republic. His background is in mathematical modelling and Data Science. He is a co-founder of the Association of Microbiologists, Immunologists, and Statisticians (SMIS) which has been providing the Czech public with data-based and honest information about the coronavirus epidemic. He is also a co-founder of a “samizdat” journal dZurnal which focuses on uncovering scientific misconduct in Czech Science.

Donate Today

Your financial backing of Brownstone Institute goes to support writers, lawyers, scientists, economists, and other people of courage who have been professionally purged and displaced during the upheaval of our times. You can help get the truth out through their ongoing work.

Sign up for the Brownstone Journal Newsletter

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.