Ros Atkins on… Israel’s war in Gaza and proportionality

Ros AtkinsAnalysis editor

BBC

BBC

Israel’s military operation in Gaza has killed tens of thousands of people, destroyed thousands of buildings, and severely restricted the supply of food.

The operation was launched after Hamas rampaged through villages, military posts and a music festival in Israel on 7 October 2023, killing about 1,200 people and taking 251 others hostage. The United Nations’ (UN) human rights body would later conclude that Hamas had committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said at the time that “like every country, Israel has an inherent right to defend itself”. He argues his country’s military operation in Gaza is a “just war” with the goals of destroying Hamas and bringing home all the hostages.

In January 2024, he said that “Israel’s commitment to international law is unwavering”. That commitment is coming under ever-increasing scrutiny.

Leading human rights organisations and some countries accuse Israel of ethnic cleansing and acts of genocide. Netanyahu denies this and has strongly criticised such allegations.

An important aspect of how international law applies to wars is the principle of proportionality.

In the words of the International Committee of the Red Cross, it means that “the effects of the means and methods of warfare used must not be disproportionate to the military advantage sought”.

BBC Verify has spoken to a range of international law experts to ask whether they consider Israel’s actions to have been proportionate.

The vast majority of them, with different degrees of certainty, told us that Israel’s actions are not proportionate. In drawing that conclusion, some reference Israel’s conduct of the whole war, some focus on events in recent months.

“I would struggle to see how Israel’s military conduct in Gaza could potentially be characterised as proportionate,” says Prof Janina Dill from the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Dr Maria Varaki, from Kings College London, told us that “it is undisputable, non-disputable, actually, that the use of force in Gaza has been disproportionate”.

Prof Yuval Shany, at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, states: “The military campaign can no longer be seen as proportionate.”

And Prof Asa Kasher of Tel Aviv University, who was the lead author of the IDF’s first code of ethics, told us the number of non-combatants killed “seems too high to be taken to result from reasonable proportionality considerations”.

How is proportionality assessed?

International law is made up of a series of agreements that most countries in the world have signed. The agreements detail what states can and can’t do. They include the UN Charter and the Geneva Conventions, both of which Israel is party to and both of which are relevant to proportionality.

International law is not set out in one place, nor is it governed by a central authority. As we will see, its meaning and application are open to considerable debate.

Regarding proportionality, international law addresses this in two distinct ways.

Firstly, when a state has the right to self-defence, the overall military response must be proportionate to the threat being responded to.

In addition, if at any point during the military operation, it ceases to be necessary and proportionate, the right to self-defence no longer applies.

For example, some argue, such has been Israel’s success in weakening Hamas, the military operation is no longer proportionate to the threat that Hamas currently poses. This, I should emphasise, is contested.

The second way international law addresses proportionality concerns each individual military action within a conflict, such as an air strike.

The expected harm to civilians or civilian buildings must be proportionate to the expected military advantage gained from that particular action.

Intent is a vital consideration here. What civilian harm is anticipated? And is the expected military advantage proportionate to this?

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

It is important to emphasise that intentionally harming civilians is always a breach of international law. Proportionality is not a consideration if this is done.

Also, while international law does allow for circumstances in which civilians are killed during the course of a military action, there is always an obligation to minimise civilian harm wherever possible.

Both areas of law are clear: whatever the provocation or the threat, there are rules and limits on what can be done – in the overall response and individual actions. They must be proportionate.

Let’s begin with the impact of Israel’s overall operation.

Civilian casualties

More than 64,500 people have been killed by Israel during its campaign – almost half of them women and children, according to Gaza’s Hamas-run Ministry of Health. The ministry’s figures do not distinguish between combatants and civilians.

Israel has challenged the accuracy of the ministry’s figures, both the overall number and the demographic breakdown, but they are quoted by the UN and others as the most reliable source of statistics on casualties available.

UN Secretary General António Guterres recently declared “the levels of death and destruction in Gaza are without parallel in recent times”.

At the start of the year, the Israeli military said it had killed about 20,000 Hamas operatives, although it has not provided evidence, and does not allow foreign media, including BBC News, free access to Gaza. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has not provided any figures for civilian casualties.

The IDF told us that it is “committed to mitigating civilian harm during operational activity” and that it “makes great efforts to estimate and consider potential civilian collateral damage in its strikes”.

Israel also accuses Hamas – which is proscribed as a terrorist organisation by the UK, Israel and others – of causing casualties by operating within civilian areas.

It has released numerous videos of what it says are Hamas tunnels running under civilian buildings, including hospitals. Israel says Hamas uses these underground networks to plan and organise attacks. Some of the freed hostages have also described being held in tunnels.

Reuters

Reuters

Prof Nicholas Rostow, former legal adviser to the US National Security Council under President Ronald Reagan and a distinguished research fellow of the National Defense University, argues that “Hamas used hospitals, schools… as a base of military operations, putting civilians at risk. That was their intention”.

Because of this, Prof Rostow says he is “not prepared to say that Israel has acted disproportionately”. He says he knows how the IDF operates and that it “bend[s] over backwards to respect the laws of war”.

But even if that is the case, Israel has still killed tens of thousands of people.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty Images

Dr Nimer Sultany, editor-in-chief of The Palestine Yearbook of International Law and chair of the Centre for Palestine Studies at SOAS University of London, is categorical. “Israel’s campaign has been disproportionate since October 2023, because of the unprecedented civilian harm it caused in Gaza,” he told us.

Gerry Simpson, professor of public international law at the London School of Economics (LSE), told us, referencing the number of people killed and other consequences for Gaza, that: “It is hard to seriously argue that the campaign has been conducted with due regard to the general principles of proportionality and distinction at the heart of the laws of war.”

Access to food

The impact on a population’s living conditions is another factor in assessing the proportionality of Israel’s overall response.

Israel’s restricting of goods into Gaza is not new. This was happening before 7 October and increased after the attack.

Then, in early March this year, Israel began a total blockade of aid into Gaza. It said it was doing so to stop Hamas stealing supplies and using them “to finance its terror machine”. Hamas denies doing this.

The blockade was condemned by the UN and many countries.

Senior UN officials accused Israel of using food as a “weapon of war”, which is a crime under international law. Such actions cannot be proportionate.

“You can never use starvation of either enemy fighters or the civilian population,” says Prof Mary Ellen O’Connell, of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “You must permit the entry of humanitarian assistance to the civilian population. That is a principle of customary international law. You cannot use starvation. There are certain weapons you can never use.”

Benjamin Netanyahu denies this is a weapon that Israel is using.

The UN also accused Israel of “deliberately and unashamedly imposing inhumane conditions on civilians”. Israel denies doing this too.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty Images

In May, Israel partially eased the aid blockade and introduced a new system of food distribution operated by a US and Israel-backed group called the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF).

More than 200 charities and other NGOs have called for the GHF to be shut down, claiming Israeli forces and armed groups “routinely” open fire on those seeking aid.

The United Nations says more than 2,000 people have been killed around aid sites and convoys in recent months. In August, it said most of the killings were by the Israeli military. Israel denies this.

Israel says the GHF’s system provides direct assistance to people who need it, bypassing Hamas interference.

But many people who need assistance are not receiving it.

The latest assessment from the UN-backed global hunger monitor (IPC) is that a quarter of Palestinians in Gaza are suffering from famine.

Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called this assessment a “tailor-made fabricated report to fit Hamas’s fake campaign”. The IPC has issued a response defending its methodology.

Aid agencies, senior UN officials, the UK government and others all say the famine and starvation in Gaza are a result of Israel’s actions.

Israel justifies the change of aid system as a necessary part of its effort to defeat Hamas. But even if it is – and that is strongly contested – as the current occupying power, Israel has obligations under international law to civilians in Gaza, including providing adequate access to food.

Netanyahu says that any food shortages are the fault of aid agencies and Hamas. Also, despite the mounting evidence, he has repeatedly denied that starvation is taking place.

Destruction of buildings

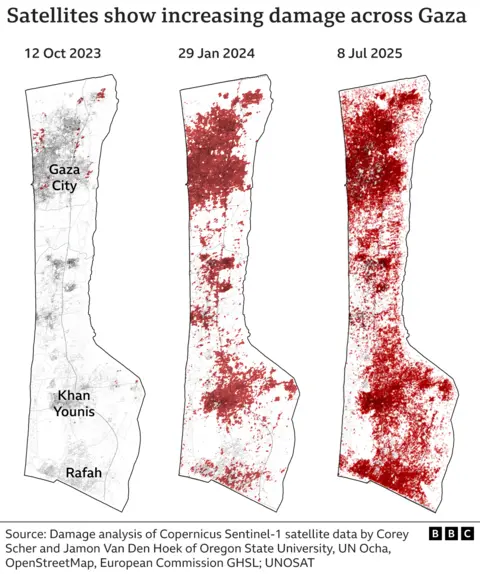

Civilian harm caused by the overall operation also includes the damage or destruction of buildings.

In May, Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, declared that “Gaza will be entirely destroyed”. That is getting closer.

The latest UN estimate is that up to 42% of buildings in the Gaza Strip have been destroyed and 37% damaged.

Prof Emily Crawford, who teaches international humanitarian law at the University of Sydney Law School, told us the “complete destruction of infrastructure necessary for the survival of the civilian population… is clearly disproportionate”.

Destruction is what is being threatened. In August, Israel’s Defence Minister Israel Katz looked ahead to an assault on Gaza City. Posting on social media he demanded that Hamas frees the hostages and disarm: “If they do not agree, Gaza, the capital of Hamas, will become Rafah and Beit Hanoun.”

These are both cities that Israel has reduced to ruins.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

As well as destroying and damaging buildings during its offensives, BBC Verify analysis suggests Israel has also systematically destroyed buildings in areas it controls.

The IDF said the “destruction of property is only performed when an imperative military necessity is demanded”.

To Israel the overall “military necessity” of its operation is not just the severe weakening of Hamas, but its complete defeat.

Former UK Supreme Court Justice Lord Sumption wrote in a recent article: “The destruction of Hamas is probably unachievable by any amount of violence, but it is certainly unachievable without a grossly disproportionate effect on human life.”

Lord Sumption told us that Israel has concluded there is “no limit to the destruction and casualties that they can inflict, provided that it is necessary to defeat Hamas”. He says: “This is plainly incorrect.”

Other experts also suggest Israel’s own legal assessments have given the government huge leeway in how it can act.

Dr Nimer Sultany believes Israel has “repeatedly invoked wild and highly permissive interpretations of the laws of armed conflict, including the question of proportionality, that defy both common sense and authoritative understandings of international law”.

Israel insists it adheres to international law and applies it correctly.

BBC Verify asked Israel’s government for the legal advice, or a summary of it, that supports its view that its overall military response to 7 October has been proportionate.

We did not receive a reply.

Assessing individual attacks

As mentioned earlier, the second way international law addresses proportionality concerns individual actions within a conflict.

Is the expected harm to civilians and civilian buildings from a particular action proportionate to the expected military gain that is sought?

In the case of this conflict, Israel’s targeting of Hamas members – and the resulting civilian casualties – has been a particular focus.

For instance, on 27 June this year there was a strike near the Palestine Stadium in Gaza City, aimed at what Israel called “a suspicious individual who posed a threat to IDF troops operating in the northern Gaza Strip”.

Reuters

Reuters

The IDF told BBC Verify: “The IDF struck a Hamas terrorist. Prior to the strike, steps were taken to mitigate the risk of harming civilians as much as possible.”

According to medics and witnesses, at least 11 people, including children, were killed by the strike.

The IDF told the BBC it has comprehensive processes to “ensure implementation with the Law of Armed Conflict”. It says senior military commanders are given “target cards” which “facilitate an analysis that is conducted on a strike-by-strike basis, and takes into account the expected military advantage and the likely collateral civilian harm”.

Sir Geoffrey Nice KC is a barrister and former prosecutor for the UN. On Israel’s calculations around the proportionality of its targeted strikes, he says: “The number of innocent Palestinians killed would seem very hard to justify by the search for an individual Hamas person, however senior that person might be.”

The organisation UK Lawyers for Israel has published a “Q&A on International Law of Armed Conflict and Gaza”. On the issue of proportionality and individual military strikes, it says “it is impossible to assess this without having the information known to the IDF commanders at the time”.

Israel doesn’t provide details of its decisions on individual strikes, so this assessment is difficult. However, patterns of individual strikes can inform our understanding of Israel’s calculations.

“The burden is now on [Israel] to prove that they were proportionate,” argues Sir Geoffrey.

The right to self-defence

Underpinning Israel’s campaign is its assertion of the right to self-defence. This is laid out in Article 51 of the UN Charter – the “inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs”.

As we said earlier, the right to self-defence connects to the first way that international law addresses proportionality.

The question being: when the right of self-defence applies, is the overall military response proportionate to the threat being responded to?

Immediately after 7 October, many countries, including the US and the UK, made clear that Israel had the right to defend itself.

In its “Briefing Note on Proportionality in Warfare”, UK Lawyers for Israel argues that “Israel is entitled, in self-defence, to enter that territory [Gaza] to dismantle that organisation [Hamas] to prevent it from ever repeating its murderous aim”.

Prof Neve Gordon of Queen Mary University, London, is the author of “Israel’s Occupation”. Recently, he took part in a two-day event which described itself as an inquiry into the UK’s role in Israeli war crimes in Gaza.

On the right to self-defence, he says: “I think it is obvious again to anyone with eyes in their head that Hamas carried out a violent attack on 7 October, massacred hundreds of civilians, and I think most states would respond to such an attack.”

But he adds that legally this remains complicated.

In fact, several of the experts we spoke to emphasised that, in this instance, Israel’s right to self-defence, as detailed in the UN Charter, is contested.

EPA

EPA

Francesca Albanese is the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories (Gaza and the West Bank). She is a fierce critic of Israel’s actions and is banned from Israel because of comments about “Israeli oppression” made after 7 October.

Albanese told us that Israel “has completely capsized the current use of principles of distinction, principle of military necessity, precautions, and proportionality in international law”.

On self-defence, she points towards the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) advisory opinion in 2004, that Israel could not invoke self-defence against a population it maintains under occupation.

Israel rejects this argument. It claims it was not occupying Gaza before 7 October because it withdrew its troops and settlers in 2005.

However, the UN still regards Gaza as occupied territory because Israel retained control of Gaza’s airspace, shoreline and most of its land border. An ICJ advisory opinion last year found that Israel’s occupation of Gaza did not end in 2005, and that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory is unlawful.

Gaza’s status before 7 October is relevant to whether the right to self-defence applies, according to Prof Ralph Wilde of University College London. Last year, he represented the states of the Arab League at the International Court of Justice in proceedings relating to Israel and Palestinian territories.

Prof Wilde told us: “Israel’s use of force after 7 October was not a new use of force. It was a continuation of that pre-existing use of force, amplifying it to an extreme level. It was, therefore, a continuation of an illegal use of force.”

Israel rejects such an argument.

There is a second reason why some believe the right to self-defence doesn’t apply to 7 October. Francesca Albanese argues that this right only applies if an attack comes from another state.

Some of the international law experts we spoke to disagree.

Lord Sumption told us such a position is “barely arguable”.

Prof Crawford, at the University of Sydney Law School, told us that “since the 9/11 attacks, many states have been prepared to accept that the right to self-defence under international law extends to uses of force against the state by non-state actors”. In other words, it does apply to Hamas and 7 October.

This debate is relevant to whether Israel’s overall response can be considered a proportionate act of self-defence.

Though Gerry Simpson, Professor of Public International Law at the London School of Economics (LSE), adds: “Even if Israel has a right to self-defence, the exercise of it has been disproportionate.”

Prof Kasher, of Tel Aviv University, argues the right to self-defence continues to apply so long as Hamas poses a threat to Israel and its population. “Self-defence is well justified as long as the goal is defence,” he says.

Whether it is the goal, though, is contested.

Israel’s goals

Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich said in May that his country’s goal was “destroying everything that’s left of the Gaza Strip”. He also talked of “conquering, cleansing and remaining in Gaza until Hamas is destroyed”.

In July, the Israeli defence minister proposed re-settling the entire Palestinian population of Gaza at a camp in the south of the territory, according to Israeli media. The UN had previously warned that the forcible transfer of an occupied territory’s civilian population is “tantamount to ethnic cleansing”.

The proposed “humanitarian city” was discussed by the Israeli cabinet, but no plans to move forward have been made public.

Israeli statements, proposals and actions are causing some to question whether its goals and its actions go beyond self-defence.

“This is not a war where the goal is defeat,” claims Prof Neve Gordon of Queen Mary University. “It is a war where the goal is destruction.”

Reuters

Reuters

Prof Gerry Simpson from the LSE told us that “the Israeli response looks more like revenge, or the continuation of a long-running erasure of Palestinian identity, than anything one could call ‘legitimate self-defence'”.

And Prof Janina Dill told us: “If we listen to Israeli security forces and Israeli decision-makers, we must understand that [incapacitating Hamas] is not anymore, or predominantly, the aim Israel is pursuing in Gaza.”

Israel rejects any such suggestions.

The IDF told BBC Verify: “The terrorist organisations in the Gaza Strip systematically violate international law and deliberately carry out military operations from within the civilian population. The IDF will continue to operate against the terrorist organisations in the Gaza Strip whenever and wherever necessary.”

A case to answer?

In late 2024, judges at the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Netanyahu, saying there were reasonable grounds to believe he bore “criminal responsibility” for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza war.

It also issued arrest warrants for former Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant and Hamas’s then-military chief Mohammed Deif, who Israel says it has now killed.

Netanyahu called the decision antisemitic, and the US later imposed sanctions on four ICC judges, claiming the court was politicised. Further ICC officials and the UN’s Francesca Albanese have also now been sanctioned.

A case was also brought to the ICJ by South Africa in 2023, arguing Israel was committing genocide. Israel has dismissed the allegation as baseless. The case is ongoing.

International justice often deals in years and decades, not weeks and months. There are limitations on what it can do during or after a conflict. And the US hostility to Netanyahu’s arrest warrant shows Israel has significant support from the world’s superpower.

However, in time, the institutions that apply international law can and do draw definitive conclusions. These rulings matter – as do the laws themselves. However imperfect, they are the rules that most countries have agreed should define what they can and can’t do. As such, they still count for a lot.

The vast majority of the experts we spoke to believe that all or some aspect of Israel’s actions have not been proportionate, in particular with regards to its overall operation. They reach that conclusion for different reasons and with differing degrees of certainty.

Prof O’Connell, of Notre Dame University, told us: “There are rules, and they’re not being complied with.”

Prof Yuval Shany, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, says there is an argument that Israel’s actions were initially proportionate but “there seems to have been, however, a point crossed at which Hamas has been weakened to such a degree that the continuation of the military campaign can no longer be seen as proportionate in nature, given its extensive scope, scale and consequences”.

And Prof Hovell of LSE told the BBC: “Proportionality in international law is a pretty blunt tool. In many modern conflicts, applying that standard can be difficult. But in Gaza, the case is, sadly, strikingly clear. Israel’s campaign has been grossly disproportionate.”

Meanwhile, the conflict continues. A much-diminished Hamas is still fighting, still holding hostages and still denying Israel’s right to exist.

Israel insists it followed international law throughout this conflict – and that its actions are proportionate. But nearly all of the experts we spoke to aren’t convinced.

Additional reporting by Jemimah Herd

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.