Legislative and practice problems in Canada’s MAiD regime

Alex Schadenberg

Executive Director

Euthanasia Prevention Coalition

Dr Ramona Coelho and David Shannon have written a critique of Canada’s (MAiD) euthanasia law that was published by the Macdonald Laurier Institute on August 6, 2025.

|

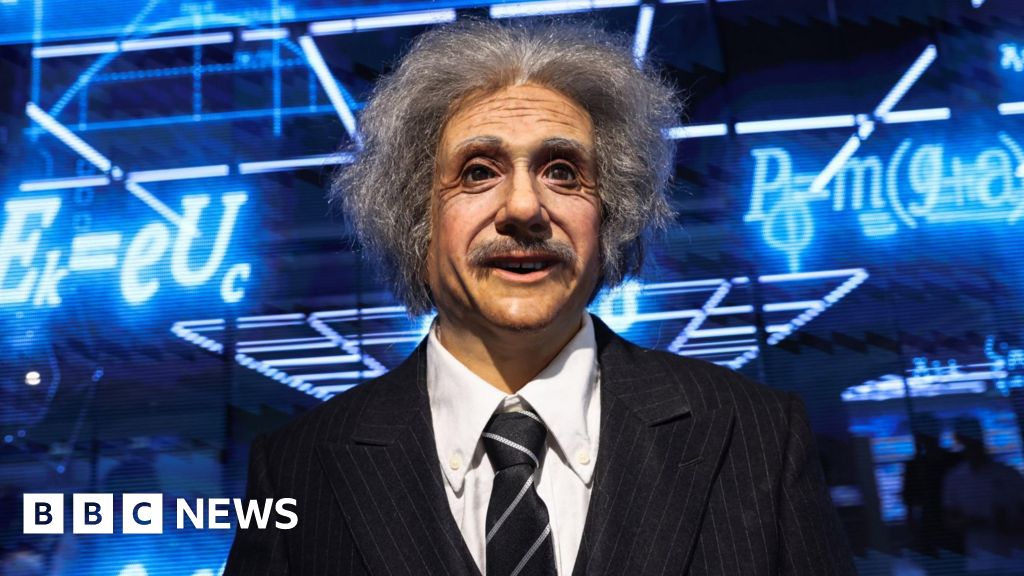

| Dr Ramona Coelho |

Coelho and Shannon are members of the Chief Coroner of Ontario’s MAiD Death Review Committee (MDRC) that has published reports several reports concerning the oversight of euthanasia in Ontario.

In their article, Coelho and Shannon outline concerns with the current euthanasia practise in Canada and they make concrete proposals for amending the law to ensure greater oversight. This article will share their concerns with the practise of euthanasia in Canada.

|

| David Shannon |

The authors first examine how Canada’s euthanasia law has developed. They explain that euthanasia was legalized in 2016 and has quickly expanded since then. In March 2021, Canada’s government passed Bill C-7 which expanded Canada’s euthanasia law. The authors write:

In 2021, Canada legislatively extended eligibility to individuals who have physical disabilities but are not near death (Track 2) and, in the near future, to individuals whose sole underlying medical condition is mental illness. As legislators and MAiD lobbyists campaign for “access” and “choice,” evidence suggests that the safeguards intended to ensure free and informed consent while protecting vulnerable populations from wrongful death often fail or are bypassed.

The authors continue:

Ontario’s MAiD Death Review Committee (MDRC) reports, government data, and investigative journalism illustrate how MAiD can be rushed forward without a thorough exploration of the reversible sources of suffering, robust capacity assessments, or alternative options such as palliative, social, and disability supports. Under some circumstances, MAiD is more accessible than basic care, particularly for those experiencing poverty, isolation, or inadequate medical and social support. This Commentary reviews the failures of current MAiD safeguards and proposes policy changes to address them. These include improving oversight, strengthening consent and capacity assessments, and ensuring access to meaningful alternatives, especially for disabled and marginalized people at risk of wrongful death under the current regime.

The authors explain the changes in Canada’s euthanasia law after Bill C-7 was passed. Bill C-7 created a two-track law whereby Track 1 approvals are based on a person having a terminal condition and Track 2 approvals are based on a person having an “irremediable medical condition.” Track 1 approvals have no waiting period whereas Track 2 approvals have a 90 day waiting period.

The authors examine the Problems with MAiD – Social suffering, structural coercion, and MAiD as default “care” and write:

Health Canada reports that nearly half of Track 2 MAiD deaths involved suffering from loneliness or isolation, while almost half indicated that they felt like they were a burden. Ontario’s MAiD Death Review Committee (MDRC) found most Track 2 recipients were low-income and 61 per cent were women, a group statistically more likely to attempt suicide yet recover with care. Less than half received mental health or disability supports and less than 10 per cent received housing or income assistance. Many did not name a family member as next-of-kin, suggesting social isolation.

A 2021 University of Guelph study found that during COVID, some disabled people were encouraged to explore MAiD due to lack of resources. And in private leaked MAiD assessor and provider forums, MAiD providers have described ending lives where suffering due to poverty, loneliness, or obesity was driving the request for MAiD.

Though providers must inform applicants of alternatives for relief, there is no obligation to ensure access or assist with navigation. Providers are not required to have expertise in relevant disability or social supports, and applicants are not required to be offered information from people with lived experience who could help them navigate existing systems and offer peer support. In practice, the appearance of choice is often not backed by real alternatives.

The authors comment on Neglect of palliative care/rushed MAiD deaths and write:

Canadians lack adequate palliative care and can subsequently suffer high symptom burden, which can drive MAiD requests. Health Canada reports high levels of palliative care before MAiD deaths but does not track the timing or quality of palliative care. This tracking is self-reported by MAiD providers, which may inflate the appearance of access. For instance, in MDRC Report 2024-4, Mrs. B, denied hospice, died quickly by MAiD after her overwhelmed spouse sought urgent MAiD access. MDRC data shows clustering of same-day and next-day MAiD deaths, suggesting some providers may be more inclined to expedite MAiD over exploring the remediation of suffering.

Dr. David Henderson, a palliative care physician with the Nova Scotia Health Authority, testified that health professionals have effectively been given “a licence to kill” without sufficient safeguards. He testified that MAiD assessments often bypass the root causes of suffering.

While polls show that Canadians prioritize expanding palliative care over MAiD, access to the former remains inadequate while MAiD expands.

The next topic is A lack of free and informed consent/ limited virtual assessments. The authors write:

As early as 2020, Ontario’s chief coroner identified cases where patients received MAiD without well-documented capacity assessments, even though their medical records suggested they lacked capacity. MDRC reports also raise serious concerns about cases where MAiD proceeded despite questionable consent or capacity. These include instances where patients showed signs of cognitive decline or were heavily sedated, or where assessments were rushed or based on minimal interaction. Some relied on prior waivers without confirming whether the patient still wished to die. Some patients were even assessed virtually, raising serious concerns about the integrity of the capacity and evaluation process.

The next topic is CAMAP’s influence on MAiD practice and Health Canada’s carelessness. The authors write:

The Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP) wields immense influence over clinical MAiD practice through educational curricula. Its work is funded by at least $3.3 million from Health Canada. CAMAP’s materials encourage providers to raise the options of MAiD with eligible patients, shifting the initiative from a patient-led request to a clinician-suggested intervention. One BBC documentary recounted how hospital staff repeatedly raised the option of MAiD to a dying woman. This cultural normalization has spread beyond MAiD specialists: a disabled veteran seeking home supports had a Veterans Affairs caseworker suggest MAiD instead.

CAMAP guidance allows for interpretation of the “reasonably foreseeable natural death” criterion to permit Track 2 patients to decline treatments, worsening their health status to make their death reasonably foreseeable, thereby qualifying them to have their life immediately ended as at least one MDRC reviewed case has documented.

Health Canada has created a “Model Practice Standard for MAiD,” which, among other troubling provisions, includes labelling all clinicians who object to providing MAiD, even in specific cases, as conscientious objectors. This designation can trigger mandatory referral obligations in certain provinces and entrenchs a system that funnels patients toward death. In a recorded CAMAP training session a trainee asks about withdrawing if MAiD is being driven by socioeconomic reasons. The expert affirms the right to withdraw but concludes, “You’ll then have to refer the person on to somebody else, who may hopefully fulfill the request in the end.” This “effective referral” mechanism subverts any pause or stopping MAiD for genuine assessment or care.

This effective referral loophole is exemplified by an Ottawa woman who was referred to a Brampton MAiD provider after multiple local assessors deemed her ineligible for MAiD.

The next topic is Legislative ambiguities and oversight failures. The authors write:

Canada’s MAiD framework suffers from significant legislative ambiguity and lacks real-time oversight. The Criminal Code defines a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” using vague and subjective terms. “Irreversible decline in capability,” “intolerable suffering,” and, for Track 1, a “reasonably foreseeable natural death, “provide no objective medical metrics or standardized thresholds” and so have been open to broad interpretation by MAiD assessors, with no requirement for external validation.

MAiD is governed under the Criminal Code of Canada, so violations such as inducement or failure to meet eligibility and procedural safeguards must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, a deliberately high legal threshold. Physicians and nurse practitioners can claim a defence of acting in good faith, even if they do make a mistake. This makes accountability for criminal negligence or abuse extraordinarily difficult to establish.

Alan Nichols, who had hearing loss and mild cognitive disabilities, was admitted under the Mental Health Act and was approved for MAiD during his admission, despite having no known terminal illness and over his family’s objections. In another case, Donna Duncan, who sustained a concussion and had been awaiting specialized care, received MAiD within days of her first assessment, despite her adult daughters’ serious concerns. Both families have had no recourse despite endless efforts, including contacting the relevant regulatory and police authorities. Former Justice Minister Lametti has insisted that oversight lies with families to make complaints after a death yet their remains no process to do so.

The next area of concern is how euthanasia is Marketed as “choice,” but international alarm over coercion and suicide contagion. The authors write:

Canada’s MAiD regime is frequently framed as an expression of personal autonomy and choice. Yet a troubling reality exists: vulnerable individuals can be steered toward MAiD in ways that mirror structural coercion and violate established suicide prevention principles.

A patient seeking emergency psychiatric care for suicidality was instead informed about MAiD. Such responses undermine the core principles of suicide prevention where messaging that promotes death and access to lethal means, of which MAiD does both, exacerbates risk of suicide.

A striking example of MAiD’s romanticization is the short film All is Beauty, sponsored by Canadian retailer Simons. It depicts a young woman, Jennyfer Hatch, surrounded by loved ones in peaceful natural settings as she reflects on the beauty of life just before having MAiD. A national news outlet revealed that Hatch had spoken publicly (under a pseudonym) about her struggles to access palliative care that she hoped would make her life better. This marketing campaign transformed a preventable tragedy into aestheticized “choice,” aiming to mask the systemic abandonment that ended her life.

Canada’s increasingly permissive MAiD legislation and practice has also drawn sharp international rebuke. Canada’s MAiD regime broadened rapidly and by 2027 is set to include requests based solely on mental illness. Quebec’s advance directive model has proceeded unchallenged despite breaking federal criminal law. In March 2025, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) condemned Canada’s MAiD expansion as inherently discriminatory and ableist. The Committee called for an immediate repeal of Track 2 eligibility (non-terminal conditions), a moratorium on advance requests and MAiD for mature minors, and urgent reforms to restore protections and real oversight.

I do not believe that euthanasia (MAiD) can ever be “safely” instituted therefore I will not comment on the possibility of improving safeguards. Euthanasia is an act of killing and it is never justified. You can read the original article for this information (Link to the article).

The authors offered great insight into the problems with Canada’s euthanasia regime. Canada should be viewed as the canary in the coal mine. Don’t follow Canada’s lead.

Ramona Coelho, MDCM, CCFP is a senior fellow for domestic and health policy, at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, an adjunct research professor of family medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, and the co-editor of Unravelling MAiD in Canada: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide as Medical Care (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2025).

David Shannon, CM, OC, OOnt, LLM is a Canadian lawyer and disability/human rights activist. Shannon has advised governments across Canada and is the recipient of both the Order of Canada and Order of Ontario for his contributions to human rights. He is the co-editor of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) in Canada: Key Multidisciplinary Perspectives (Springer, 2023).