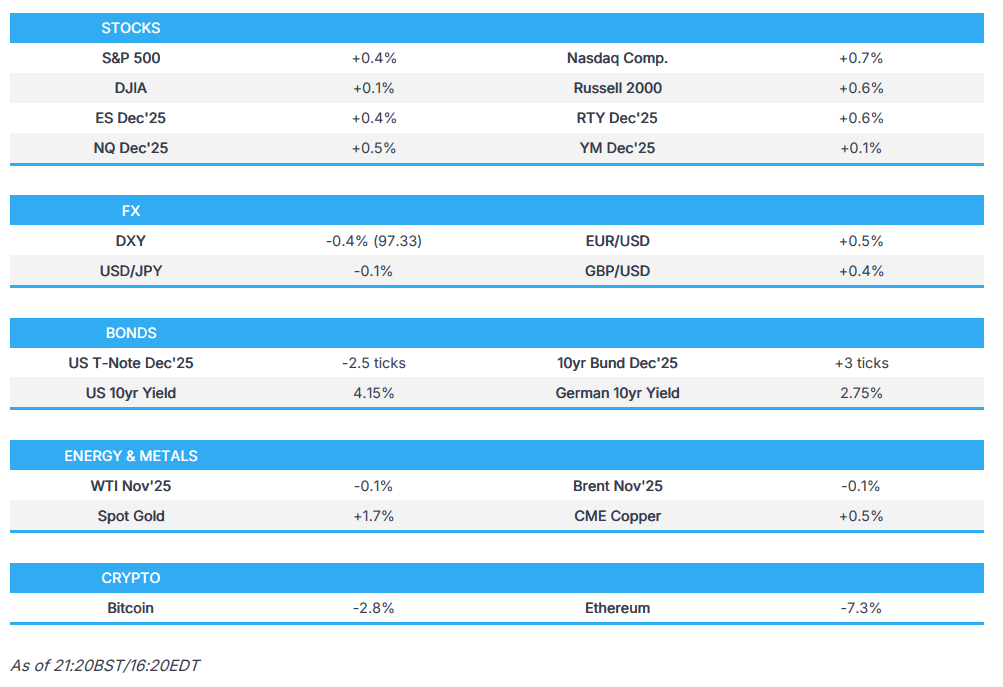

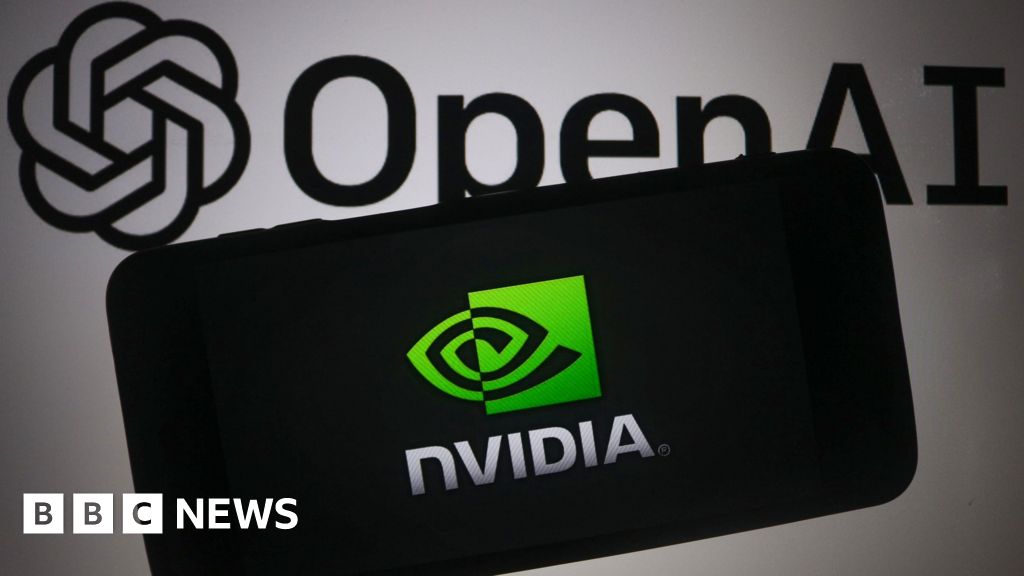

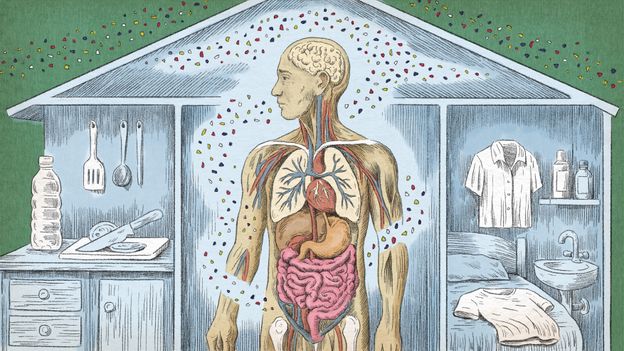

Your kitchen is full of microplastics. Here’s how to eat less of them

Ally Hirschlag and Martha Henriques

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont

Microplastics gush out of our taps and flake off cookware. They find their way into the yolks of eggs, and deep into meat and vegetables. But if we take certain steps, we can eat less of them.

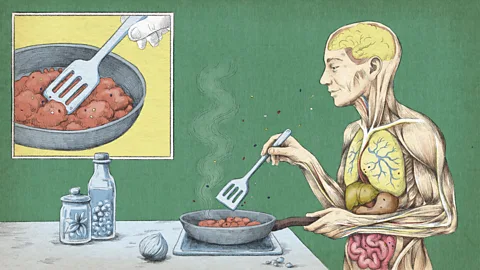

You can’t see them, but they are there, hundreds of miniscule particles of plastic lurking in your steak. As it cooks in a hot pan, these unwelcome guests liquify, oozing into the meat before solidifying again as it cools down on your plate. And they’re not just in steak. Unwittingly, you are eating them all the time.

These interlopers in our food are microplastics and nanoplastics, particles of less than 5mm or between 1 and 1,000 nanometres respectively. But how do they get into our food? And, in a world infused with bits of plastic, what can we do to reduce exposure in our diets?

If you take a closer look around your kitchen, you’ll start to recognise where microplastics enter our meals: they flake off the spatula you use to cook breakfast, leak from the plastic water bottle you put in your child’s backpack and float in the cup of tea on your desk. They’re also buried deep within the foods we eat, from hamburgers to honey.

Once you start looking for them, the exposure points for microplastics can quickly feel overwhelming. But, importantly, it is also possible to make changes to reduce the amount of microplastics we are exposed to in our kitchens.

“There’s a lot of low-hanging fruit in your house that’s really easy to address,” says Sheela Sathyanarayana, a professor of paediatrics and adjunct professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

“I do feel like it gives people a sense of control over their own lives, and we do have that a little bit more than we might think.”

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont

Food

Microplastics are in fruit and vegetables, honey, bread, dairy, fish and meat from hamburgers to chicken. They are inside the yolks of eggs (and in the whites too).

One study of 109 countries found the amount of these plastics people typically consumed in 2018 was more than six times what it was in 1990. Microplastics can get into our food when plants take them in by the roots, or animals consume them in feed. (Read more about how microplastics infiltrate the food system.)

“If you farm on a piece of land that was previously industrial and the soil is contaminated, [there is] potential for those plants to accumulate the contaminants in the soil,” says Sathyanarayana. Once that the crops are harvested, there are many more opportunities for contamination during processing. “Factories use a huge amount of plastic to be effective and to have high throughput for their products.”

For some foods, it is possible to get rid of some of the microplastics before you eat them. One study in Australia found that people were typically consuming 3-4mg of plastic per serving of home-cooked rice, and up to 13mg per serving of pre-cooked rice. The microplastics were just as present in rice that was packaged in paper, as in rice that came in plastic packaging. However, the researchers found that rinsing the rice reduced the microplastics served up by 20-40%. Washing meat and fish, too, can reduce microplastics – but not eliminate them.

For other foods, rinsing is impossible. Salt often contains microplastics due to contamination at mining and processing points. A 2018 study found that 36 out of the 39 salt brands analysed contained microplastics. Sea salt had the highest levels of microplastics, likely due to the high levels of microplastic pollution in the world’s lakes, reservoirs, rivers and oceans.

Both Sathyanarayana and Annelise Adrian, a senior programme officer with the plastics and material science team at World Wildlife Fund, are proponents of switching to fresh, whole foods or, at the very least, avoiding ultra-processed foods whenever possible. “The more ultra-processed a food is, the more likely it is to have high plastic contamination, because there are so many touch points in a factory making that food,” says Sathyanarayana.

Reducing the amount of plastic in the food chain will take more than changes within our individual kitchens. Globally, if the amount of plastic debris polluting the environment was cut by 90%, it could halve the amount of plastics consumed by people in the most affected countries.

“Plastic is a cheap, great material,” says Vilde Snekkevik, a marine biologist and microplastics researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research. “The problem is just that we’re overusing it. It’s everywhere.”

Water

Whether it comes from a tap or from a bottle, water is another notable point of exposure to microplastics. One study found the simple act of screwing a plastic bottle cap on and off dramatically increased the amount of microplastics found in the water it carried. With each twist on or off, it generated 553 microplastic particles per liter of water.

“Studies are coming out showing that there are way more micro- and nanoplastics in bottled water than previously thought,” says Adrian.

Microplastics are also commonly found in tap water. One UK study found them in all 177 samples of tap water tested, with no distinguishable difference in microplastics concentration with bottled water. Similar findings in China, Europe, Japan, Saudi Arabia and the US suggest this is a worldwide problem.

But if given the option, drinking tap water may be a better way to reduce microplastic exposure, where supplies are safe to do so. Adrian says investing in a decent filter makes a noticeable difference. Even a simple carbon filter, such as the one found in a water filter pitcher, can remove up to 90% of microplastics.

However, even if your water is low in microplastics, if you’re planning to add a plastic-containing tea bag to make a cup of tea, it can release around 11.6 billion pieces of microplastic and 3.1 billion pieces of nanoplastic into your cup. Plastic is often used in small quantities to help seal bags that are otherwise made of paper. Some manufacturers have moved to plastic-free bags.

Packaging and containers

Then there’s the plastic that much of our food comes packaged in.

“Food stored in plastic inevitably will contain microplastics,” says Adrian. “That can also include plastic-lined aluminum cans, like a can of beans.”

Simply opening plastic packaging releases a burst of microplastics. Whether you use scissors, tear a packet open with your hands, cut it with a knife or twist a lid off, it can generate up to 250 bits of microplastic per centimetre, an Australian study found. “Needless to say, repeated scissoring/cutting/sliding processes at the same position are akin to sawing to generate mulch,” the study authors note.

The age of a plastic container can also make a difference. A study in Malaysia looked at reusable melamine bowls, to find that after 100 washes the microplastic release was an order of magnitude higher than after the first time the bowl was washed. (Other materials, such as silicone, may behave differently as they age.)

Even if food is only in a container for a short time, there is still ample opportunity for contamination. In China, a study of microplastics from several different types of takeaway food container estimated that people who have five to 10 takeaways per month might be consuming 145-5,520 pieces of microplastic from the containers their meals come in.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Kitchen utensils

Now we’ve got our food out of its packaging or storage container, next comes the preparation.

The starting point for many dishes is the chopping board. One study looked at individual slices made on a chopping board, and estimated that between 100 and 300 microplastic or nanoplastic particles could be generated per millimetre of cut. A 2023 study found that one type of board, made from polyethylene, was estimated to release between 7.4-50.7g (7.4-1.8oz) microplastics a year. Another type, made of polypropylene, would release around 49.5g (1.7oz) per year. For context, 50g (1.7oz) is roughly the weight of a generous serving of breakfast cereal.

It’s worth noting though that this was a small study, and microplastic release varied between different people’s chopping styles as well as between board types – a release of that much plastic would leave your chopping board in tatters after a few years of use.

“You start looking and it’s like, yes of course, I can see [the grooves] there,” says Snekkevik, who published a 2024 review on sources of microplastics in the kitchen. “So, where did the plastic go? It must have gone somewhere.”

Sometimes, it goes straight into the food chopped on it. In the UAE, researchers reported in 2022 that meat bought at a butcher and at a supermarket contained microplastics originating from plastic chopping boards. These microplastics melted when the meat was cooked, and then solidified again as the meal cooled. Washing meat thoroughly for three minutes reduced but did not eliminate the microplastics inside it, the researchers found. Analysis of one used butcher’s board estimated that 875g (30oz) had been lost from it by the end of its lifetime.

Scratched non-stick cookware can also release an estimated thousands to millions of microplastic particles per use, making them another overlooked source within the kitchen. Even brand-new non-stick cookware used with a soft silicone whisk releases significant numbers of microplastics. Likewise, plastic mixing bowls and blenders release particles with each use. Blending ice around for 30 seconds, for example, releases hundreds of thousands of pieces of microplastic.

Silicone is sometimes suggested as a safer alternative to plastic utensils, but Adrian says there isn’t concrete evidence that it sheds fewer microplastics. “While silicone is technically more stable and withstands higher temperatures than single-use plastics, the issues of leaching and microplastics aren’t fully avoided,” she says. That said, considering its stability, she does use some silicone in her own kitchen.

Snekkevik notes that silicone does indeed degrade under very high heat. “So, it’s definitely a good alternative, and would require a bit more [than plastic] to fragment. But I wouldn’t feel comfortable saying, yep, go for silicone all the way,” says Snekkevik. Other alternatives for some kitchen items are glass and stainless steel, she notes.

There are also green-chemistry-based bioplastics, which are designed to biodegrade (unlike traditional plastic) in both the environment and the body. “In essence, the body has evolved to metabolise biomaterials and has not evolved to metabolise synthetic materials,” says Paul Anastas, professor in the practice of chemistry for the environment at Yale University in New Haven, US. He says that green chemistry allows us to create plastic materials with fewer risks. “It’s benign by design,” he says.

However, many plastics, such as polylactic acid PLA straws, have been touted as biodegradable but turned out not to be. Sometimes these plastics simply fragment quicker into microplastics, says Snekkevik. “They’re not, you know, the golden, perfect alternative yet.”

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont

Heat

Now the ingredients are prepared, it’s time to cook.

As far as heat is concerned, hotter plastics get, the more microplastics they tend to release. One study found that plastic containers warmed in the microwave for three minutes could release up to 4.22 million microplastic and 2.11 billion nanoplastic particles from a single square centimetre of plastic. Using similar containers in the refrigerator can also release “millions to billions” of microplastics and nanoplastics – but over a much longer period of six months, the study found.

Putting a hot drink in a disposable plastic cup also generates microplastics. One study tested several varieties and found that cups made from polypropylene holding hot water at 50C (122F) released the most microplastics – for all types of cup, there was less contamination when the contents were cold. Examining the cups afterwards, the researchers found the hot contents had damaged the plastic surface. The team estimated that someone using disposable plastic cups once or twice a week might drink between 18,720-73,840 pieces of microplastic a year.

There’s a rule of thumb that happens to follow the famous cookbook Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, written by chef and food writer Samin Nosrat. Adrian says that these four components can break plastic down into microplastics faster. In a plastic mixing bowl, water with salt releases threefold more microplastics than salt-free water, as the salt crystals rubbed against the bowl surface. In addition, Sathayarana has found that high-fat foods also contain higher concentrations of certain additives from plastic that can be harmful to health.

Cleaning up

Now the meal’s over, next comes washing the dishes.

Disposable kitchen sponges are yet another source of micro- and nanoplastics. For those that had a harder and a softer surface, it was the former that came with a higher risk of shedding microplastics. As they wear down, kitchen sponges can release up to 6.5 million pieces of microplastic per gram. Adding detergents and other cleaning products to a sponge may make the sponge release even more microplastics.

For other common plastic cleaning products, there’s still very little research on their microplastic release. Whether microfibre cloths release microplastics during cleaning was a much-overlooked topic of research at the time Snekkevik and her colleagues published their review in 2024.

However, synthetic textiles are well known to shed large quantities of microplastics, and they are thought to be a primary source of plastic pollution in the ocean.

What to do about a kitchen full of plastic

Snekkevik urges against a knee-jerk reaction of throwing away all your plastic kitchen utensils and appliances. “Even after writing this paper, I do still have certain items in my kitchen that are plastic,” she says. “I’m not going to just throw everything out and be like, that’s it.”

One strategy is to focus on items that show obvious signs of damage – such as anything obviously scraped, cut up, flaking or melted. When it appears to be time to change the item anyway, Snekkevik says she’ll generally choose a plastic-free replacement. “But I wouldn’t go through my kitchen and throw everything out right now, because that’s also not necessarily the environmentally friendly way to do it.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Beyond your plate

Food and drink may be the most direct way microplastics get into our digestive systems, but it’s still far from clear what effect it has on us. The research to date on the health effects of microplastics in our guts is inconclusive and few studies have been done in humans. Some scientists have suggested it might disrupt the microbes that live in our guts or that some of the smaller particles may even pass into our blood stream.

Some of this foreign material may simply become lodged inside our bodies.

“Fossil-based plastics, in their micro- and nano- forms, have been detected in virtually every organ in our bodies that have been studied, including arteries, brain, blood, placenta and testicles,” says Anastas.

More like this:

• What do the microplastics in our body do to our health?

• How do microplastics get into the food system?

• Can magnets tackle microplastic pollution?

It’s possible that much of the plastic inside us might not cause health issues, says Sathyanarayana. “The argument could be made that the particles can be lodged in a place and be inert in that area,” she says.

Adrian adds that there’s also no consensus on how long plastic stays in the body, or whether it accumulates over time. So the microplastics you’ve already eaten and drunk today might not be destined to stay in your body forever.

Indeed, at least some of the microplastics we regularly eat have been observed passing straight out the other end.

—

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.