Why Organizations Die While Cities Live Forever

Why do organizations and companies die while cities seem to live on? Why did the Western Roman Empire end in 476 A.D while the Eastern counterpart lasted for almost another 1,000 years?

Although both Empires fell, many of the cities in both have continued to the present. Why?

While the answers can be approached on multiple levels: cosmological, theological, physical, political, etc., this essay will only focus on the social, the level which we can tangibly experience and possibly influence.

Lifespans of organisms, companies, organizations, and cities are extensively, and very readably, covered in Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies. Geoffrey West reviews the work done at the Santa Fe Institute exploring the allometric scaling equation that relates energy utilization to lifespan. Organisms and companies scale “sublinearly:” organisms based on mass and companies based on economy of scale and profit. Cities on the other hand scale “supralinearly” based on population and value innovation and idea creation. Nonprofits seem to follow an ill-defined and fluid intermediate pattern that still needs more exploration.

The concept of Entropy has been expanded from its original concept of loss of energy experienced in transfer to include randomness, ambiguity, and disorder in multiple systems: statistical mechanics, information, decision-making, social systems, and organizations. Organizational sustainability depends upon a given organization’s ability to mitigate the effects of such entropy.

In a closed system, entropy invariably increases and is irreversible. Jia and Wang emphasize that the organization’s effort to mitigate the effects of entropy is dependent upon the members’ ability to mitigate it personally. They recommend a four-dimensional control model:

- Increase learning, opening the individual and therefore the organization to new ideas.

- Consciously focus on goals.

- Be open to constructive change.

- Understand that a certain amount of risk-taking will be necessary.

Over the past few years, I have experienced the “death” of several organizations that were important to me. Though never reaching the rank of Eagle Scout (I stopped at the penultimate level of Life Scout), the Boy Scouts of America played a pivotal role in my youth. I spent my Junior undergrad year with an organization that facilitated the study of American students at the University of Vienna. It was an incredible life-changing experience (my future wife was also a student), but what I remember most was the ability of many students with vastly different life experiences being able to come together to form an almost organic bond.

My professional life was marked by participation in two organizations that were similar in the ability to meld individuals into something larger than themselves. One was a hospital that rose from a seemingly ordinary community hospital into a major medical center within the span of a decade. I had worked there as a surgical technician, medical student, and intern, and ended as Chief of Ophthalmology and elected Chief of Staff. The second was a subspecialty society that devoted its efforts to creating a premier educational program for the entire United States and Canada.

I participated in a Master’s of Medical Management degree (MMM) cohort at a major business school, where I learned much of what has formed the concepts behind this essay. Finally, my wife, children, and I were members of a Spirit-filled church for over 30 years that grew into a spiritual force that literally spread through the entire world.

All these organizations had a common characteristic: they were significantly more than the sum of the parts. They all had a “noble cause” that energized the participants to stretch their efforts and impact the world in which they operated. Yet within a short period of time all of them either atrophied or toppled altogether. Why?

In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Dan Pink explains that money is not the primary motivator many believe it to be. Instead, the most effective motivators are: the deeply human need to direct our own lives, to learn and create new things, and to do better by ourselves and our world. Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose are far more potent energizers than financial gain by itself.

Warren Bennis, the “Father of Academic Leadership Studies,” mentored Dave Logan, my own mentor at the USC Business School. In Tribal Leadership: Leveraging Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization, Logan and his co-authors described the results of more than 10 years of empirical study on the critical role Organizational Culture plays in Organizational Performance. Logan and I went on to expand the definition of Organizational Culture of Edgar Schein to: “The pattern of, and capacity for, constructive adaptation based on a shared history, core values, purpose and future seen through a diversity of perspectives.”

Organizational Culture is a meme and is propagated through an organization by verbal and non-verbal communication. As a meme, it changes both belief and behavior. It brings a conscious or subliminal desire to spread itself to other members of the organization.

Although the cultural meme can strongly influence an organization, it is not immutable. External and internal pressures and counter memes can change or erase its influence.

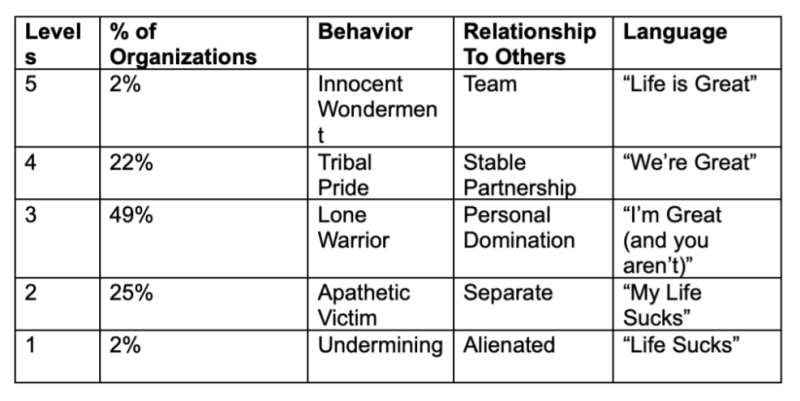

In Tribal Leadership, Logan and his co-authors described 5 levels of Organizational culture, along with a description of behavior in organizations at that level and the corresponding tagline:

Each of the organizations I personally experienced and described above had achieved a Level 5 or high Level 4 culture but failed to maintain it. They either were transformed into other entities that failed to maintain their “noble cause” or ceased to exist entirely. In the majority of instances, they failed to keep the necessary balance between the “shared” components (“history, core values, purpose, and future”) and the “diversity of perspectives.” Some focused an excessive amount of their resources and time on their “product” but neglected spending adequate time building their culture. In other cases, leadership lost sight of the importance of facilitating conversation with the members and listening to their concerns. They forgot their “customer.”

This point was explored in a recent Brownstone article by Josh Stylman, “How Specialization Enables Systemic Evil.” Many important observations are made in Stylman’s essay–too many to enumerate here–but what struck me most was his point that specialization blinds even the sharpest to the big picture. Leaders can easily lose sight of Organizational Culture as one of their primary concerns. They can become so busy chopping wood that they forget to sharpen the axe.

Organizational Culture is vital as it is the means to counter the inevitable march of Organizational Entropy. The Culture of the organization is often taken for granted and presumed to always be there. Nothing could be further from the truth. While Organizational Culture takes effort to advance, it can be lost very quickly, and once lost, it is much more difficult to regain. There are, however, specific tools to both advance as well as guard it. Examples include: using generative future-based language in communication, personal accountability using “triads,” closure of “structural holes” to increase diversity of information, and a matrix-based organizational structure instead of a hub-and-spoke relationship.

While Organizational Leaders play an important role in this process, their main contribution is facilitation, not imposition. Organizational Culture is an emergent process. It must be authentic and is an integral quality at all levels, not just upper management.

There are important lessons for our present situation as we attempt to operationalize the gains we have made in the political arena, as well as the Medical Freedom Movement. The example of the tradition of Afternoon Tea at the Santa Fe Institute is especially relevant regarding the facilitation of an emergent and authentic Organizational Culture. It is relatively simple and non-taxing of resources, yet exceedingly powerful.

This “formalized informal gathering” allows individuals from diverse disciplines to gather to share their knowledge and network with colleagues who may be outside their own professional network. The weekly Brownstone Writers Group Zoom meeting is another example, providing members a platform for a broad exchange of insights from multiple backgrounds and experiences, even if they are geographically dispersed.

Such intellectual cross-pollination has been described by Steven Johnson in Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation. This cross-pollination is also the driving force behind the periodic Pumps & Pipes conferences in Houston:

Pumps & Pipes is a cross-industry network of innovators focused on solving problems. We focus on activities that allow for convergence innovation to take place through workshops, projects, and events. We believe this approach will lead to significant advancements in the aerospace, energy, and medical industries.

The name comes from the serendipitous collaboration between Lazar Greenfield, a surgeon, and Garman Kimmel, a petroleum engineer, on a filter to prevent pulmonary emboli, yet not occlude the inferior vena cava. It was based upon much larger devices that prevented sludge from occluding pipelines. This knowledge would certainly have been closed to a surgeon reading only the surgical literature or talking only to others in his profession.

Much more successful medical devices evolved through expansion of the depth of knowledge of the means to avoid and treat pulmonary emboli. The actual Kimray-Greenfield filter has been supplanted, but the concept of collaboration between individuals with similar problems, but very different situations, remains. It is the breadth of knowledge that leads to radical jumps forward, and I believe it is precisely what Josh Stylman so eloquently described.

As Alan Lumsden, one of the founders of the Pumps & Pipes conference, stated in 2022:

What can we learn from one another? What is inside the other person’s toolkit? A lot of solutions are already out there but sometimes we don’t have the ability to see into their toolkit. This has become the driving force behind Pumps & Pipes throughout the last 15 years.

When an organization’s openness to outside information allows and encourages innovation, it ceases to be closed, and the result is a decrease in Organizational Entropy. If we want the Medical Freedom Movement to flourish and gain in influence, we must likewise make a conscious effort to advance our individual learning and expand both the depth and breadth of our knowledge and experience, and share that knowledge and experience with others. These actions will advance the culture of the organization as a whole and maximize our individual and collective performance.

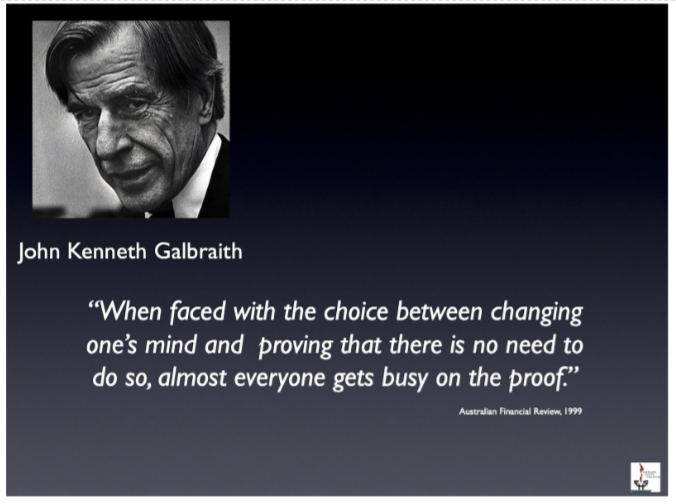

Unfortunately, this will be seen as a threat by some as there are stakeholders who have a vested personal interest in the status quo or in only one particular aspect of the struggle:

We all must guard against our own myopic views and welcome the authentic discussion of alternative interpretations or concepts. In short, we must continue to advance our own Organizational Culture and:

Continue to constructively adapt to a changing landscape based on our shared history, core values, purpose, and future seen through a diversity of perspectives.

If we do not constructively adapt to the emergent landscape and recognize the emergent opportunities we may not have even imagined, we run the risk of concentrating on winning small battles but ultimately losing the war. We must concentrate on openness and curiosity, looking in the “other guy’s toolkit” but still remaining true to our history, core values, and purpose. With this purposeful approach, we will have the greatest chance of achieving the future we all imagine.

-

Russ S. Gonnering is Adjunct Professor of Ophthalmology, Medical College of Wisconsin.