Why Industrial-Scale Cyber Scamming of US Victims Is Thriving In Burma

Every day, people in the United States and many other countries are being scammed—by phony customer service operators, romance fraudsters, and perpetrators of more complex cryptocurrency investment scams.

But those being scammed out of retirement savings, or college funds, probably do not realize the person on the other end of the phone is likely another victim, who has already paid with their freedom.

Revelations in recent months about the existence of vast scam centers along Burma’s border with Thailand, run by Chinese organized crime syndicates and human traffickers, have highlighted the sheer scale of international cybercrime.

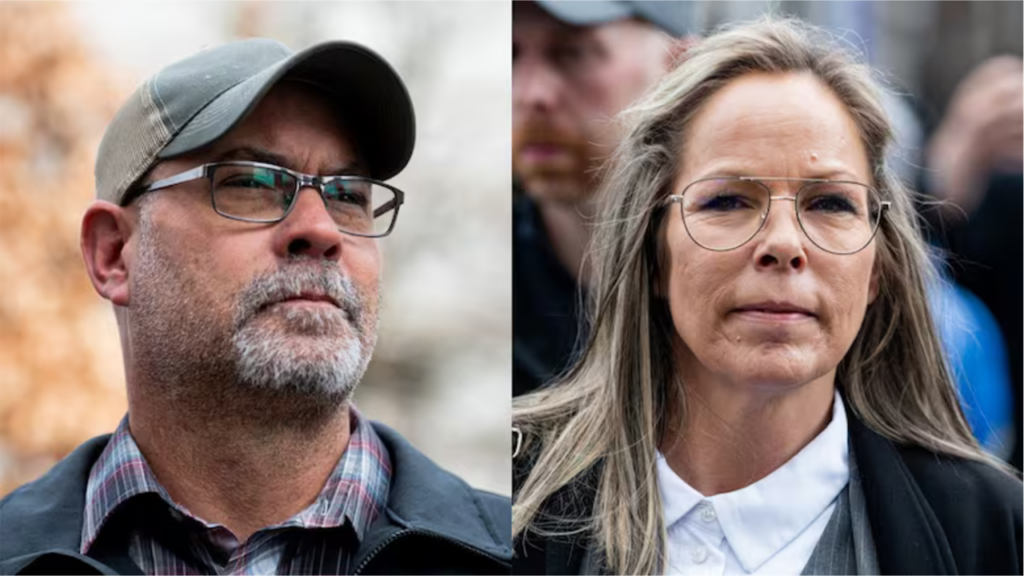

She is based in Mae Sot, Thailand, just over the border from the cybercrime hubs, and has spoken to hundreds of scammers.

“These people have no other choice. It’s scam somebody or be electrocuted, scam somebody or be locked into a prison with your hands handcuffed above your head for days or weeks with no food or water,” Miller said.

“That is, obviously, the very severe side of the victimization that happens.”

“The annual losses to cybercrime globally is over $10 trillion, or put it another way, $32 billion a day,” he told The Epoch Times.

Matthew Hogan, a detective with Connecticut State Police and an officer on the Secret Service Financial Crimes Task Force, said the scammers in Burma (also known as Myanmar) were working on a variety of frauds, including romance scams and duping bank customers over the phone.

But he told The Epoch Times the biggest growth was in long-term scams known as “pig butchering,” which involved luring people into fake cryptocurrency investments.

“They see the victims as being the pigs, and they are fattening them by creating this lure of incredible investment opportunity. So the pig gets fattened…and at some point it’s time to butcher the pig,” Hogan said.

Hogan said the scams usually started with someone receiving an SMS or a direct message on social media from a stranger, who would then begin building a “rapport.”

Hundreds of Fake Domains

“They may not directly say it, but they‘ll mention it in passing, like ’I’m going to buy my uncle a Rolex from the Rolex store‘, and they’ll send pictures of herself at the Rolex store, or send a selfie from inside of a Porsche,” Hogan said.

Eventually, the scammer will steer the conversation around to investing in cryptocurrency and persuade their victims to invest in what are completely fake crypto schemes.

He said the whole scam was also supported by hundreds of fake domains that purport to show the fluctuations of the cryptocurrency investments.

“They have hundreds of domains that these scammers are operating at one of these scam centers. The people who are human trafficked are technologically savvy, so they’re building websites, they’re building iOS and Google compatible apps, they’re designing the domains, they’re designing the conversations, everything,” Hogan said.

In the past two months, several cyber scam centers in Burma, close to the border with Thailand, have been closed down, and thousands of workers—many of whom claim to have been trafficked—were left stranded.

But last month, Gen. Thatchai Pitaneelaboot, who is in charge of the Thai police investigation, said up to 100,000 people were still working in cybercrime hubs in the Myawaddy region of Burma.

‘Incredible Remorse’ of Scammers

“Many of them have taken people’s life savings … and they come out with incredible remorse, and survivor guilt, and incredible trauma about what they have done,” Miller said.

“A lot of these people are religious people, they’re either Christian or Muslim, and they have quite a bit of moral issues with what they have done.”

She said Chinese syndicates, with links to Triad organized crime groups, were running the cyber scam centers, with the connivance of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DBKA) and the Border Guard Forces (BGF), groups who are loyal to the Burmese military government.

Miller said the same syndicates were also operating in Laos and Cambodia.

“We have seen Myanmar’s to be more brutal overall as far as treatment [of workers goes.] And it’s uniquely challenging because of the civil unrest in Myanmar, it’s a more lawless place that is hard to penetrate,” she said.

Miller said the 8,000 workers rescued from the cyber scam centers this year had come from 29 different nations.

She said that number included 3,000 from China, 1,000 from Ethiopia, 600 from Indonesia, more than 500 from India, and then smaller numbers from Kenya, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and several African countries.

Jenkinson said all of these scams relied on data.

‘Data Is Money’

He said: “In the 1930s legendary bank robber Willie Sutton was asked why he targeted banks. He said, ‘That’s where the money is.’ Cybercriminals attack servers because that’s where the data is, and data is money. It’s the new gold now.”

Jenkinson said these hacking gangs would hold companies to ransom, for encrypted keys to decrypt the information and release it back to the company.

But the data thieves would also sell it on to other organized crime gangs who would use it to target vulnerable people and defraud them out of millions of dollars every year.

“It’s known that over 90 percent of companies that pay the ransoms do not get all the data back, and the data is later found on the dark web,” Jenkinson said.

Hogan said he had spoken to numerous victims of what he called a scam epidemic all over the United States.

“We’ve had people put HELOCs [Home Equity Lines of Credit] on their home, we’ve had people almost taking out second mortgages, we’ve had people … lose their houses,” he told The Epoch Times.

“We had a woman we were assisting out in the Midwest, that took a loan out on her house, and ended up losing it, so she had to foreclose on it, we’ve had the whole gamut. So it really is a crisis. This is, like the scamdemic of all scamdemics.

“I’ve talked to victims all over the country, I talked to a lot of them all over the world, too, and it’s definitely not just a U.S. thing by any means.”

Jenkinson said, “What we’re talking about is organized crime, utilizing disorganized cyber security for massive rewards, non-attributed and non-taxable.”

Jenkinson said most big corporations just ignore this data theft and do not publicize the fact that they have become victims.

“They’d rather ignore it, and … [think] some of their customers will get scammed, but hopefully not all of them,” he said.

“What happens is the trickle-down economy. Let’s say a bank made a £1 billion profit last year and they suffer a cyber attack.

“Well, what they do is they say, ‘Okay, we’ve allocated within a bit of creative accounting, that that cyber attack cost $250 million, so we deduct off the $1 billion profit.’”

Jenkinson said that CEOs and CFOs at the top of the world’s leading banks and credit card companies do not personally stand to lose money from cybercrime, so they have no incentive to tackle it.

“Because the banks aren’t doing their job properly, they’re non-compliant, and they’re insecure—but they are very rarely held to account—fraud and scams are rife,” he said.

“The data is plagiarized and exfiltrated from servers that aren’t secure, which means that everyone that uses that bank or facility literally have their feet held to the fire, and they are totally unaware.”

Downside of Outsourcing

“Over the years we’ve outsourced, wrongly and foolishly, to India and other parts of the world, and that’s been one of our downfalls,” he said.

Jenkinson said that from around 2010, the advent of cloud computing allowed companies to outsource domain name systems (DNSs) and content distribution networks (CDNs) to server farms around the world, to speed up data retrieval and reduce latency.

But he said the data centers run by companies such as CloudFlare, Akamai, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon were not secure enough.

Jenkinson said while this allowed the National Security Agency and other intelligence agencies to access the data of people they were investigating, it also meant criminals “can exploit that very same data for ransomware, for fraud, cybercrime, everything else.”

He said it was no coincidence that cyber crimes had gone up exponentially since 2010.

“The reason why is because, love him or hate him, Edward Snowden showed the world what America had been doing for 20 or 30 years, and what the adversaries of America said is … if they can do it, so can we. And that’s been cybercrime,” Jenkinson said.

The Epoch Times reached out to the Federal Reserve, the American Bankers Association, and the Data Center Coalition about the issues raised in this article, but received no responses by publication time.