The COVID-19 Tsunami – Fact or Fiction? – The Daily Sceptic

The Response – Appropriate and Proportionate?

The two questions above are absolutely fundamental and are being ignored by the official Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry, and its UK equivalent, despite the thousands of hours and millions of £s being spent on them. In frustration Common Knowledge Edinburgh recently set up its own Scottish People’s Covid-19 Inquiry and I was asked to address these questions directly. It was a fascinating, often moving, and lively day – talks are available here, and below I summarise the evidence I presented and the conclusions I reached.

A tsunami of deaths?

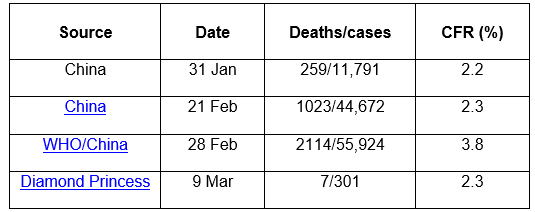

Prior to the first lockdown at the end of March 2020 what did we know about the likely impact of this new disease to help us calibrate our response, particularly in terms of its mortality ? The table below shows some of the very first estimates of case fatality ratios (CFRs) that emerged:

At the end of January 2020 China reported a CFR of 2.2%, then the following month 2.3%. One week later the WHO/China Joint Mission had somehow found double the number of deaths and 10,000 more cases estimating the CFR at 3.8%. Finally, the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship quarantined in a Japanese port because of COVID-19 on board, identified seven deaths amongst 301 cases giving a similar CFR to the earlier Chinese estimates.

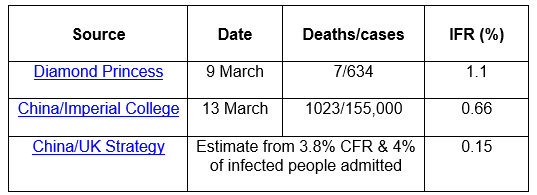

In a previous article I have commented about the unusual and over-inclusive definitions of COVID-19 cases, hospitalisation and deaths, as have others, and some have also questioned the specificity of the COVID-19 tests (likelihood of tests being positive with other viruses), all of which tend to exaggerate official statistics. However there is an additional concern about CFRs. Early estimates of CFRs for a new disease come from hospitals, which of course only admit seriously ill people, and therefore miss in their count of cases those patients with milder disease in the community – potentially a far larger group. For this reason CFRs overestimate mortality. What we all wanted to know back in spring 2020 was the likelihood of us succumbing if we caught COVID-19 – this statistic is the infection fatality ratio or IFR (deaths/everyone infected rather than only hospital cases). Table 2 gives three pre-first lockdown estimates of IFR:

Continued widespread testing of the 3,711 passengers and staff on the Diamond Princess identified a further 328 people who had been infected and provided the first estimate of IFR at 1.1%, half of the CFR. And this figure is likely to be higher than the UK would ever experience because of the older age distribution on the cruise ship. Next came an article from Imperial College which estimated the proportion of infected people in China from testing of returning ex-pats from China to Europe giving an IFR of 0.66%. Finally I derived an estimate of IFR using the highest Chinese CFR of 3.8% and a figure taken from the UK Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, which suggested 1-4% of patients with flu are likely to be admitted to hospital, using the upper limit of 4%. This suggests an IFR of 0.15%, and even if 10% of patients with COVID-19 are admitted the IFR would still only be 0.38%.

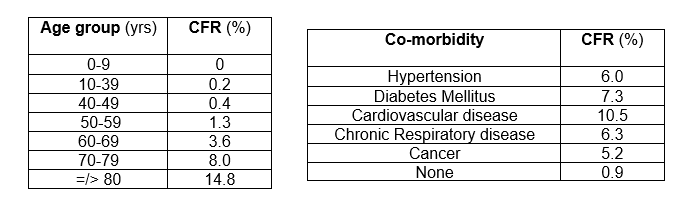

So the IFR seems to be below 1%, or to put it another way, 99% of people who develop COVID-19 survive. This estimate is very helpful in assessing the potential impact of this new disease, but it has the limitation of being an overall population average – so it would also have been helpful to know which groups in the population are at greater risk and which at lower risk. Fortunately we had such data back in spring 2020 too, for example from the second Chinese CFR article in Table 1 which provided such “epidemiological characteristics”. This article concluded that COVID-19 was highly transmissible, that most people had only mild symptoms, that the CFR was “low” (2.3%), and importantly It observed that most deaths occurred in those over 60 years and those with co-morbidities, see tables below:

Turning firstly to age, and bearing in mind that these CFRs are all higher than the IFRs, it is clear that the average CFR of 2.3% hides huge variation across the age spectrum from 0.2% in 10-39 year-olds to 14.8% in those 80 years or older. It is also worth noting that even in the oldest age group over 85% survive an encounter with COVID-19.

The list of common chronic diseases or co-morbidities in table 3b all appear to increase the risk from COVID-19 with the highest being cardiovascular disease at 10.5%, compared to the risk with no co-morbidity of 0.9%. Unfortunately no cross-tabulation of age by co-morbidity was presented in this article to show for example the risk to those under 60 years with no co-morbidity, likely to be significantly lower than the rates in table 3a, nor the risk to older people with multiple co-morbidities, likely to be higher than those in table 3a and 3b.

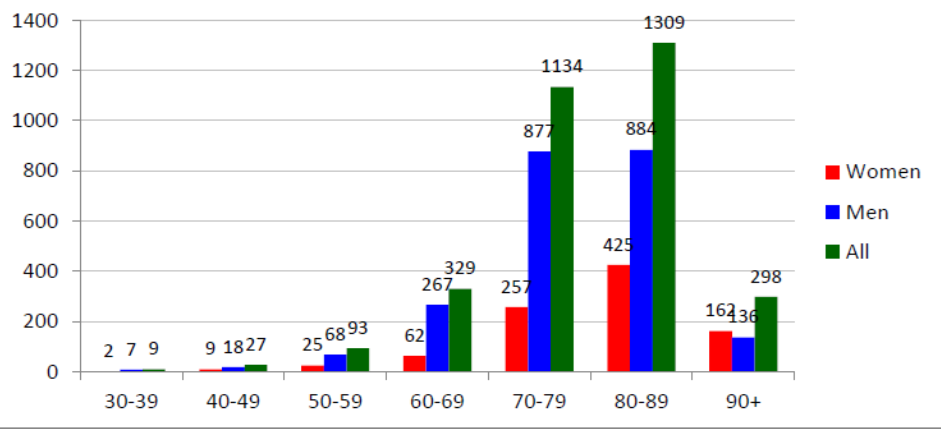

Figure 1 below shows numbers of deaths reported in the first Instituto Superiore di Sanita report from Italy on March 20th 2020 – as well as confirming that there are few deaths below 60 years it shows far more deaths in men:

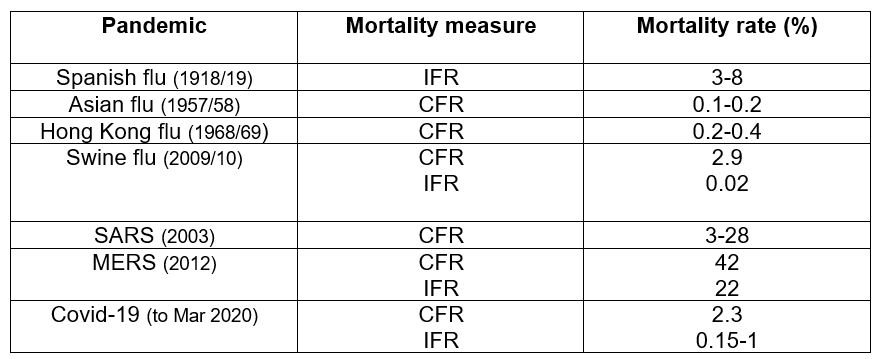

So, what should we have made of these data back in March 2020? Did we face a major health emergency, a veritable tsunami of deaths? To assess this and give perspective a comparison with previous pandemics is helpful and Table 4 does this, presenting mortality on pandemics over the last century or so:

There are various estimates of global deaths from Spanish flu but most suggest an IFR of between 3% and 8%. The UK Pandemic Strategy quotes a WHO CFR estimate of 0.1-0.2% for Asian flu and 0.2-0.4% for Hong Kong flu, whilst the more recent Swine Flu had a higher CFR at 2.9% but lower IFR at 0.02%. Turning to coronaviruses, the first Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2003 had a widely differing impact, in large part thought to be due to the different age groups affected, from a 3% CFR in Beijing to 28% in Taiwan. Finally Middle East Respiratory Syndrome had the highest CFR at 42% and IFR at 22%.

Although the comparison is bedevilled by not having IFRs on all pandemics it is still clear that in terms of mortality COVID-19 with a CFR of 2.3% and an IFR below 1% is no Spanish flu, SARS or MERS, and seems closer to Swine, Asian or Hong Kong Flu. We also have to bear in mind the exaggeration of COVID-19 deaths (numerator) discussed earlier, although there was also an exaggeration of cases/infections (denominator), so the net effect is uncertain. In terms of transmissibility it also seems more similar to these previous flu pandemics than to SARS or MERS (which had low transmissibility). However, there is an important proviso in the mortality comparison, and this is that unlike these flu pandemics COVID-19 does not affect young people significantly. The steep age stratification of mortality from COVID-19 is unusual and it reduces its impact in terms of “years of life lost”, and also provides opportunities for its management.

Were these early estimates for COVID-19 mortality borne out by subsequent studies and would we have erred if we’d relied on them? Well, one of the first seroprevalence studies, where the proportion of people infected is based on sample surveys of serum antibodies to SARS-CoV2, was reported from Santa Clara county in California at the end of April 2020. The authors estimated that 54,000 people had been infected at the time when known COVID-19 cases were only 1,000 and deaths 94. This gives an IFR of 0.17%. Then in early May Iceland, which at the time was conducting PCR testing more widely than any other country, identified 10 COVID-19 deaths, 1,798 cases and estimated that there were 3,640 infected citizens, suggesting an IFR of 0.3%. Following these early post-first lockdown estimates other studies came thick and fast so Ioannidis published a systematic review of seroprevalence studies globally on January 1st 2021 and concluded that 0.23% was the best estimate of IFR. Subsequently he reviewed all systematic reviews and in May 2021 produced an overall global estimate of 0.15% (with significant local variation). So subsequent studies confirmed that the IFR was below 1% and almost certainly significantly below 0.5% globally, with IFRs for individual countries largely dependent on their age structures. So the early IFR estimates and conclusions that COVID-19 was likely to be more similar to Swine, Asian or Hong Kong Flu in its impact are supported by subsequent studies. Thus if you take official statistics at face value, COVID-19 would seem to be a serious disease putting some at significant risk, but presenting minimal risk to healthy people below 60 years – so no tsunami.

Comparing the standard and COVID-19 pandemic response

Table 4 demonstrates that over the last 50 years or so there has been considerable experience of pandemics, and pandemic plans have been reviewed and refined after each. So what did these plans say we should do to respond to a new pandemic?

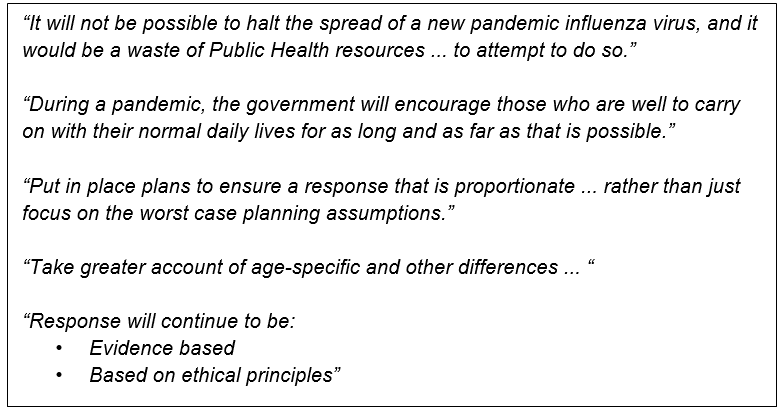

Firstly, measures to reduce transmission of a virus included (i) respiratory and hand hygiene (use of tissues, safe disposal then hand washing), (ii) isolation of those with symptoms to minimise onward transmission, (iii) contact tracing and school closures were only recommended early in a pandemic if at all, whilst (iv) mask wearing was reserved for healthcare staff, and finally (v) the importance of accurate public messaging without causing panic was emphasised, with tailored messaging to those at highest risk (but not amounting to shielding or “focused protection”). The quotes below from the UK Pandemic Preparedness Strategy of 2011 give a flavour of the recommended approach:

These plans were based upon regular systematic reviews of the evidence on what was effective, conducted over the years by the Cochrane Collaboration and the WHO, the latest of which was published in September 2019, only a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic started. And of course they were based upon the experience of managing previous pandemics, particularly over the last 50 years. So how does the actual response to COVID-19 compare with this standard response?

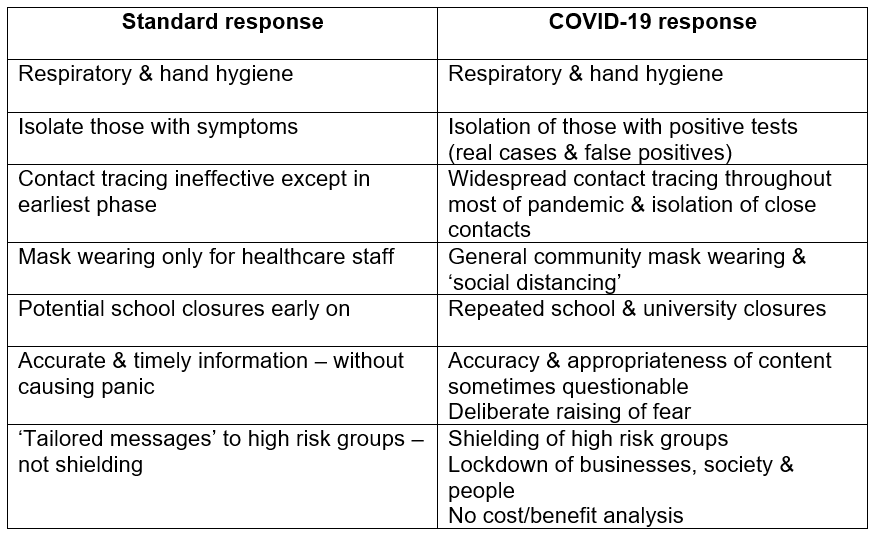

Table 5 provides a direct comparison on the measures to reduce transmission and clearly demonstrates an exaggerated response to COVID-19 in most areas:

Widespread community testing at its peak generated thousands of false positives each week with isolation not only of them, but also their contacts. There was also population-wide use of masks, frequent and long school closures, public messaging that was not always accurate nor appropriate and used to deliberately spread fear, lockdown of businesses and people in their own homes, and the transformation of the NHS into a COVID-19 service. The measures taken were not only contrary to the evidence and previous experience but they were also implemented despite the harms that inevitably resulted having been predicted beforehand.

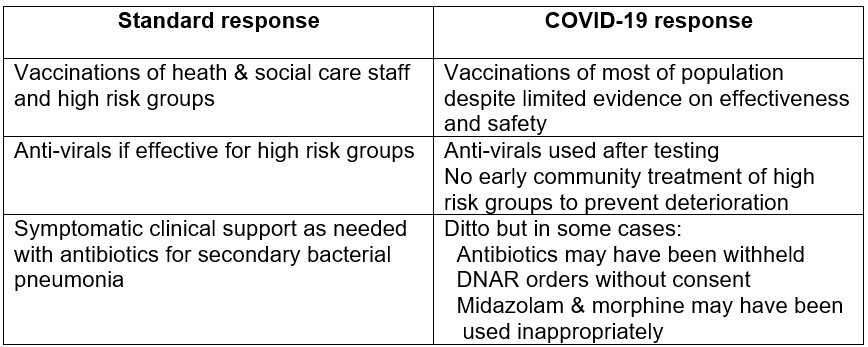

Table 6 provides a similar comparison of standard and Covid-19 responses for measures to protect and treat individuals:

The coercive population-wide rollout of COVID-19 vaccines despite limited evidence on their effectiveness and safety was unprecedented. The failure to use and evaluate alternative drugs (in addition to antivirals) to prevent deterioration in high risk patients despite evidence was also remarkable. Finally, major lapses in medical ethics in relation to the vaccine rollout, antibiotics, DNAR orders and use of midazolam and morphine were alarming.

Conclusions

Any critical review of the COVID-19 response cannot but conclude that most of it was inappropriate – in that it was not based on firm evidence or experience, nor did it seek to balance risk from the disease with the benefits and potential harms from interventions at both a population and individual level, making informed consent impossible. Furthermore, as the IFR estimates before the first lockdown were below 1%, the response was also disproportionate. The enormous and widespread harms that would result from such an inappropriate and disproportionate response should have been clear to those advocating it.

So what would a more appropriate and proportionate response have involved? Well, firstly it would have involved honesty, providing the public with accurate information on the levels of risk and how this varied by age, sex and co-morbidity. And accurate information on what they could do to minimise the risk to themselves and those around them by use of respiratory and hand hygiene, avoiding contact with anyone symptomatic and isolating if they were symptomatic themselves, and shielding for those at higher risk during the first few waves. Healthy people below 60 years should have been advised to carry on as usual. Accurate information on the evidence for the effectiveness and safety of drugs for early treatment and vaccines was essential, with clarity about remaining areas of uncertainty. Then our governments and authorities should have treated the public as adults and let them make their own decisions, rather than taking a coercive and authoritarian approach. In other words our governments and their advisors should have followed standard public health practice and existing codes on medical ethics and informed consent.

Dr Alan Mordue is a retired consultant in public health medicine.