Sussan Ley: Does Liberal Party drama show Australian politics still has a problem with women?

Sussan Ley and the glass cliff: Does Australian politics still have a problem with women?

Getty Images

Getty Images

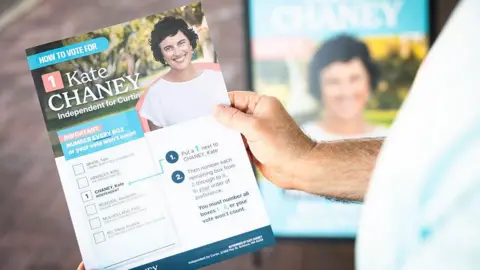

When Sussan Ley made history as the first woman to take the reins of Australia’s Liberal Party, she insisted this was a pivotal moment for the party – or what was left of it anyway.

She had broken through the glass ceiling: an invisible, patriarchal barrier which keeps women from positions of power.

But to many, Ley’s glass ceiling looked an awful lot like a “glass cliff”, and it felt like it was only a matter of time before she lost her grip and slipped off it.

The glass cliff describes a phenomenon where women and other minorities are promoted to leadership roles during times of crisis, setting them up for a high risk of failure. In essence, it says that when women are finally allowed to ascend to the top, it’s frequently so they can take the fall.

Elected as leader after the most resounding election defeat in the history of the modern Liberal Party and amid internal party chaos, Ley didn’t even survive a year.

On Friday she was pushed out by Angus Taylor, who argued she didn’t have what it takes to turn the opposition’s fortunes around. He won a leadership ballot 34 to 17, with Senator Jane Hume elected as his deputy.

Ley’s backers claim she was never given the chance to succeed, with some saying gender played a role. Her opponents say her demise has nothing to do with that and everything to do with performance.

The messy saga has reignited conversations in Australia about its progress towards making its politics look more like its population.

‘Crisis on every front’

Whoever took over as Liberal leader after the Labor landslide in May last year was always going to have a tough job.

They had to unify the polarised factions of the party and manage an increasingly toxic relationship with their coalition partner of eight decades, the National Party – a small but vocal and often mutinous cohort of rural MPs.

They had to overhaul a policy platform which was comprehensively rejected by voters. And they had to do this while balancing the demands of the more conservative sects of the Coalition with the more progressive desires of voters in the urban areas where they were ravaged at the polls.

And they had to repair the Liberals’ reputation with women, who have deserted them en-masse after a string of allegations of misogyny levelled during the Coaliton’s previous term of government, which ended in 2022.

“There was just crisis on every front… it’s classic glass cliff,” says Michelle Ryan, Director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership and one of the researchers who coined the term.

Getty Images

Getty Images

From her very first press conference as leader, Ley was aware of what this looked like.

She and her supporters insisted she had been selected exactly for this moment, because she was the right person to lead the Coalition through it.

She is a moderate who can appeal to city slickers, yes, but one from a bush electorate who can speak National. She’s been in parliament for 20 years and was a cabinet minister for five. With an unusual but impressive resume that includes time as a pilot and a sheep musterer, Ley says she has spent her entire life breaking down barriers, challenging assumptions and making room for herself in places women weren’t always welcome.

Some critics say the idea of a glass cliff itself is offensive, that it diminishes women’s achievements and assumes they can’t successfully lead out of a crisis, when in fact many in the community feel women fare better in them.

“As far as political analysis goes, it is just wrong,” Ley wrote in an op-ed for the Women’s Agenda shortly after she took over.

“There is no doubt that all too often women are left to clean up the mess… But when the most successful political party in our nation’s history picks a leader, it doesn’t do so based on chromosomes.

Few are saying she didn’t. But the Liberal Party famously passed over Julie Bishop in 2018, an electorally popular and long-serving minister who had been the party deputy for 11 years.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Political observers say there was a sense Ley was only keeping the seat warm for Taylor, whose first leadership bid failed by a slim margin after a controversial choice in running mate.

The glass cliff phenomenon doesn’t paint the true picture of Ley’s tenure though, says Niki Savva, a veteran political commentator and former Liberal Party advisor.

“Sometimes I get really impatient with the argument that all this is happening to Ley because she’s a woman. She hasn’t been given a fair go because she’s a woman,” she tells the BBC.

“Maybe a tiny bit, but that is not the real reason… Sussan Ley is the architect of her own fortunes.”

She promised not to make unilateral calls as leader, which seemingly opened the door to relentless pressure – public and private – from her peers. She promised to listen to the electorate on climate, but facing opposition from the conservative members of the Coalition, rolled back her party’s promise to reach net-zero by 2050.

And though she played a leading role in pushing the government to hold a royal commission into antisemitism in the wake of the Bondi attack – which she says she’s proud of – critics accused her of politicising the tragedy. She also oversaw two short-lived but ugly break-ups between the Liberals and Nationals.

“Political leaders are judged on their performance, not on their gender,” Liberal Senator, and prominent Taylor backer, James Paterson said on Thursday.

“Newspoll shows she’s at negative 39 personal approving approval rating. That is the worst performance of an opposition leader in 23 years.”

The driver behind her abysmal approval rating, Savva says, is her lack of conviction on issues she said she cared about.

“If she had gone out there and staked out her territory, gone out and fought for it, then maybe her position would not be as dire as it is today.”

Ryan, though, argues both things can be true.

“It really isn’t about whether Ley is qualified for the job or not… It’s not even about her performance in this job,” Ryan says.

“It’s about when is it that the party will put a woman ahead.”

Women still rare at the top

Julia Gillard, the nation’s first female prime minister, is the only woman aside from Ley to lead one of its two major parties.

She said at the end of her misogyny-plagued tenure in 2013: “Being the first female prime minister does not explain everything about my prime ministership, nor does it explain nothing about my prime ministership.”

It’s true that representation in parliament has grown dramatically since Gillard’s era – largely driven by her party, Labor, who more than 30 years ago set ambitious quotas, both for selecting female candidates in winnable seats, and promoting them into leadership.

While the Coalition party rooms remain about a third female, the Labor caucus is now majority women – 57% – a historic achievement. And there is gender equality in cabinet too.

But women are still rare at the very top.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Anthony Albanese’s leadership team is the first from Labor without at least a female deputy since 2001, aside from a three-month blip in 2013. Albanese was part of that woman-less leadership team too.

And though Penny Wong is senate leader and foreign minister, women still tend to have more junior cabinet roles or positions in non-cabinet ministries.

“Being able to say we’ve had a female prime minister, that’s great, we’ve just got to get beyond one,” Ryan says. “You have to do it again, and then you have to do it again.”

But over the three decades Labor has used to increase its gender diversity through quotas, doyens of both the Liberal and National parties, even Ley herself, have been arguing they don’t need them – to the frustration of many of the women in their ranks.

Gender shouldn’t matter in politics, they say, something which critics say fails to acknowledge the reality that it long has, and still does.

“Instead of, as a woman, getting out there and arguing for quotas, standing up for them, Ley came out with this line, which I just thought was BS, about being a zealot for getting more women into parliament, but agnostic on quotas,” Savva says.

“Well, what the hell did that mean? And what did she do about it subsequently? Big fat zero.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Analysts say this reluctance from the Liberals to champion strong female candidates has helped fuel the rise of independents. More than 70% of crossbench MPs in this parliament are women, many of them so-called “Teal” candidates who have won in traditionally blue, Liberal seats.

Ley, who after the leadership spill announced she would resign from parliament, said there was “no doubt” it had been “a challenging time to lead the party”.

“It is important that the new leader gets clear air, something that is not always afforded to leaders,” she said, a parting jab at her successor.

This episode is unlikely to help resolve the Liberal Party’s quandaries.

Election post-mortems, as well as consistent feedback from polling and interest groups, point towards the desire for a more diverse Liberal Party that reflects modern Australia, and a more cooperative, stable one.

At best, recent events show disorganisation and disunity, commentators say. At worst, they’re another show of a stubborn Liberal Party reluctant to learn from its mistakes.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.