‘It shocked white middle America’: How the Mississippi Burning murders sparked landmark change in the US

Getty Images

Getty Images

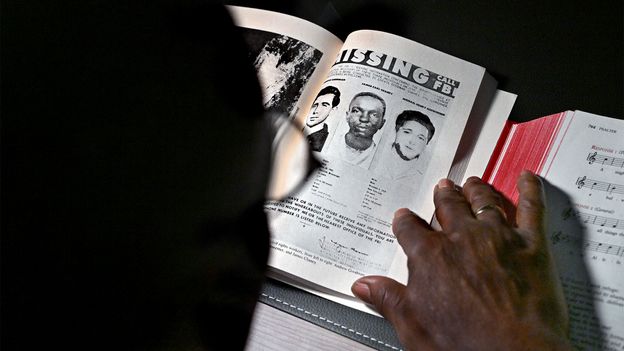

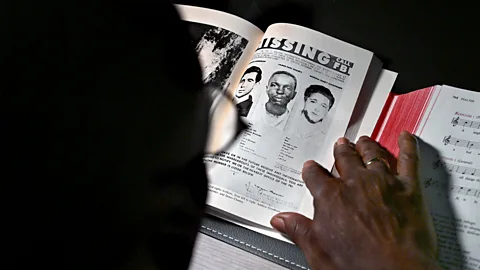

Sixty-one years ago, the bodies of three murdered civil rights workers were found in the Deep South. The public’s response to the FBI’s Mississippi Burning investigation provided the impetus for enacting landmark civil rights legislation across the US.

When Julian Bond, the co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) sat down to talk to the BBC in July 1964, it was just over two weeks since the disappearance of young civil rights workers in Mississippi had begun dominating the US news headlines.

Warning: The following video contains discriminatory language, used in a historical context, which some may find offensive.

The three men had been part of “Freedom Summer” – a three-month initiative launched by SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality (Core) and other civil rights organisations, to encourage as many black people as possible in Mississippi to register to vote. In 1961, despite roughly 45% of Mississippi’s population being black, less than 7% were registered to vote. Freedom Summer’s goal was to tackle the laws and fear tactics that were being used to disenfranchise the state’s black voters.

Hundreds of volunteers, many of them college students from northern states, travelled down to the South to help establish Freedom Schools. These centres, as well as teaching classes in black history and civil rights, helped potential voters pass the literacy tests and fill in the forms the state required, so that they could cast their votes. Twenty-four-year-old Nancy Stearns was one of the young volunteers who had travelled from the North to participate in the project. “I believe that this situation in the US must be changed,” she told the BBC in 1964. “As it is now, it’s an extremely unjust society. It doesn’t change by itself, it only changes through some sort of force, some sort of agitation, if you will. And I want to put my life in and be part of this attempt at change.”

But the Freedom Summer initiative had sparked intense and often violent resistance from white supremacists and local authorities in Mississippi. The campaigners, and the black voters who attended the lessons, faced constant intimidation and violence. Black churches were routinely torched, and activists threatened and assaulted.

On 21 June 1964, the three young Core staffers – James Chaney, a 21-year-old black native of Mississippi, and his two white colleagues, Jewish New Yorkers 20-year-old Andrew Goodman and 24-year-old Michael Schwerner – travelled to investigate the firebombing of Mount Zion Methodist Church in Neshoba County. The black church had been targeted by the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) because it acted as an organising centre for the Freedom Summer campaign.

There are people in this country who will do anything to stop democracy from becoming a reality – Julian Bond

After examining the church’s charred remains and interviewing members of the congregation, who had suffered savage beatings at the hands of the Klansmen, the three men left the site to return to the Core office. On their way, the station wagon they were driving was stopped by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price for an alleged traffic violation. Chaney was the driver, and yet Price arrested all three men and took them to the Neshoba County jail in Philadelphia, Mississippi. They were not allowed to call anyone on the phone or, initially, to pay the fine.

Because of the febrile atmosphere at the time, if Core staff did not return when they were expected, it was procedure to ring around local police stations and hospitals. But despite Core’s phone records showing the police station was called at around 17:30, Minnie Herring, the jailer’s wife, denied that anyone inquired about the three men. At around 22:30, the three civil rights workers were finally allowed to pay the fine, and were released from custody. Price told them to leave the county. They were not heard from again.

Mystery sparks huge response

Bond believed that the disappearance was designed to spread fear among the people working on Freedom Summer. And while it did cause a couple of volunteers to have second thoughts, he said that for many of the activists it served to underscore the importance of what they were trying to achieve: getting black people registered to vote. “They are determined they are going to continue doing what they are doing… and the disappearance of those three just shows them exactly what they are up against,” Bond told the BBC in July 1964. “That there are people in this country who will do anything to stop democracy from becoming a reality.”

Unlike previous victims of racial violence, the missing men prompted a huge response from the US Justice Department. Attorney General Robert Kennedy classified the case as a kidnapping so it came under federal jurisdiction, and he ordered some 150 FBI agents from the New Orleans office to comb the area to find them. They were joined in the search by troops from a nearby naval airbase, and on 23 July the men’s burnt-out car was discovered near a swamp. But there was no sign of the three civil rights workers.

The investigation was codenamed Miburn – short for Mississippi Burning. As it gathered momentum, it began to attract widespread interest from the press. “It was huge, there were news reporters camped out in front of our apartment building,” David Goodman, the younger brother of Andrew Goodman, told BBC Witness History in 2014. “The police were there 24 hours a day just to control the crowds. It was very hard to focus on anything.”

He believed that the difference between the law enforcement response to the Mississippi Burning case and the response to previous attacks on civil rights workers was that two of the missing men were white. “It shocked white middle America and the sense was, how could this happen to white people? This is a part of the story that’s not told that often, when a majority sees their own being hurt. They sit up and say, ‘Jesus this could happen to my kids or me,'” he said. Schwerner’s wife Rita, who also worked for Core, told reporters at the time: “It is only because my husband and Andrew Goodman were white that the national alarm has been sounded.”

The extensive coverage of the Mississippi Burning investigation would cast a spotlight on the racial discrimination and violence that were taking place in the US, galvanising public and political support for the Democrats’ proposed civil rights legislation. Andrew Goodman’s brother told Witness History that it created “an atmosphere for change” that enabled US President Lyndon Johnson to sign The Civil Rights Act into law on 2 July 1964. “And that was a sensibility that the president understood. He was a shrewd politician and he used it to get the civil rights act passed. And it’s kind of a miracle that it passed, but it did and it changed our country.” The landmark legislation would ban discrimination and segregation in public places, schools and employment.

But speaking to the BBC just five days after the Act was passed, Bond said that the SNCC’s offices were still receiving reports of violent opposition from white residents and police when black people tried to use previously segregated places in the South. Bond pointed to an attack which had happened in Alabama just a few days before where the police force “became the mob”, attacking 60 or 70 black people who were trying to get into a white cinema in Selma. But even in the face of these attacks, “we think this bill is the law of the land and the federal government is behind it, and we intend to go right ahead and exercise our rights under this new law,” Bond told the BBC.

Throughout July, as FBI agents continued to scour the Mississippi swampland looking for the three missing civil rights activists, they repeatedly came across the remains of other black murder victims. One of these was the body of 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby, who was discovered wearing a Core T-shirt. Charles Eddie Moore, who had been one of 600 students expelled from Alcorn State University in April 1964 for participating in civil rights protests, was found alongside the body of his childhood friend Henry Hezekiah Dee. The two 19-year-olds had been abducted in May 1964 by the KKK, who had brutally beaten them with sticks before drowning them in the Mississippi River. In 2007, 71-year-old James Seale, a former policeman, was convicted of the killings after Charles Marcus Edwards, a church deacon and self-confessed Klansman, admitted to participating in their abduction. He was given immunity in exchange for his testimony. The bodies of five other black victims of violence, discovered by the FBI while looking for the missing activists, have never been identified.

On 4 August, after six weeks of searching, FBI investigators finally uncovered the bodies of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman buried in a red-clay dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. They were tipped off to their location by an informant, who would later be identified as Mississippi Highway Patrol officer Maynard King. All three had been shot, and Chaney had been tortured before he died. Despite this, state authorities refused to prosecute the case, citing insufficient evidence.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The Justice Department was unable to bring murder charges, since those were under state jurisdiction, so instead charged 18 men with conspiring to violate Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman’s civil rights. Among the accused were a Baptist preacher and KKK leader called Edgar Ray Killen; Samuel Bowers, the Imperial Wizard of Mississippi’s White Knights of the KKK; the officer who had arrested them, Deputy Price; and his boss Sheriff Lawrence Rainey. Sheriff Rainey himself had been previously accused of shooting an unarmed black motorist. Initially, the presiding judge tried to dismiss the charges brought against most of the defendants. He claimed those indictments could only be brought against law enforcement officers, but he was overruled by the US Supreme Court.

A catalyst for change

The Mississippi Burning trial began in earnest in October 1967 in front of an all-white jury of seven men and five women. One of the accused, Klansman James Jordan, agreed to testify for the prosecution in exchange for a plea deal. He set out in detail for the jury the conspiracy that had taken place to abduct and murder the civil rights workers. While the three civil rights workers were being held in jail, Deputy Price had contacted Killen, who rounded up a lynch mob of Klansmen in two cars to intercept the three men after they left jail. As Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney drove towards the county line, Deputy Price, who was trailing their car, stopped them again and took them to a deserted rural road. Here he handed them over to the KKK. Jordan confessed to shooting Chaney and said another Klan member, Wayne Roberts, had killed Schwerner and Goodman. They had then used a bulldozer to hide the bodies in the earthen dam.

On 21 October 1967, the jury found seven of the 18 defendants guilty, including Jordan, Roberts, Bowers and Deputy Price. Ultimately, none of them would serve more than six years in prison. Sheriff Rainey would walk free. As would Killen, who had recruited the killers, after a juror said she could not convict a preacher.

In 1988, a fictionalised version of the investigation into the murders was made into an Alan Parker film called Mississippi Burning, starring actors Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as characters loosely based on John Proctor and Joseph Sullivan, the real-life FBI agents who led the search for the missing men. The following year, the state’s Attorney General Michael Moore decided to reopen the case, with the FBI turning over more than 40,000 pages of evidence from its original 1960s investigation.

Alamy

Alamy

The following year, Bowers would also find himself in court. As head of the KKK, the authorities believed he had been responsible for ordering more than 300 attacks on black civil rights activists during the 1950s and 60s. Bowers had stood trial four times before, but the all-white juries had failed to reach a verdict. In 2006, at the age of 73, he was finally sentenced to life imprisonment for masterminding the firebomb attack that killed black civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer in 1966. That same year, the FBI would launch its Cold Case Initiative to re-examine more than 125 unsolved cases from the civil rights era.

Both Bowers and Killen would ultimately die in prison. In 2016, the decision was made to close the investigation into the three civil rights workers’ deaths due to the belief that because of the passage of time, it would be unlikely that any more convictions would be secured.

When the case was closed, the families of the victims stressed that what was important was recognising the many people who had been attacked or killed while fighting for equal rights.

“The civil rights period was not about just those three young men,” Chaney’s sister, the Reverend Julia Chaney Moss, told the Guardian newspaper in 2016. “It was about all of the lives.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.