How India Gives report: Ordinary citizens power $6bn in charity annually

Revealed: The billions given to charity by ordinary Indians every year

Soutik BiswasIndia correspondent

Getty Images

Getty Images

India’s philanthropy story is usually told from the top down.

It features corporate social responsibility (CSR) budgets, billionaire pledges and splashy foundations. But a new report argues that the real engine of Indian generosity is far more prosaic – and vastly larger.

The How India Gives 2025 report, produced by the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy (CSIP) at Ashoka University, challenges the conventional narrative that organised, institutional money dominates the country’s giving landscape. Instead, it points to a quieter colossus: households.

According to the report, India’s total household giving is estimated at 540bn rupees ($6bn) annually, including cash, in-kind contributions and volunteering.

About 68% of respondents report giving in some form. Of this, 48% is in kind – such as food, clothing or other household goods – followed by cash donations (44%) and volunteering (30%) with non-profits, religious institutions or community groups.

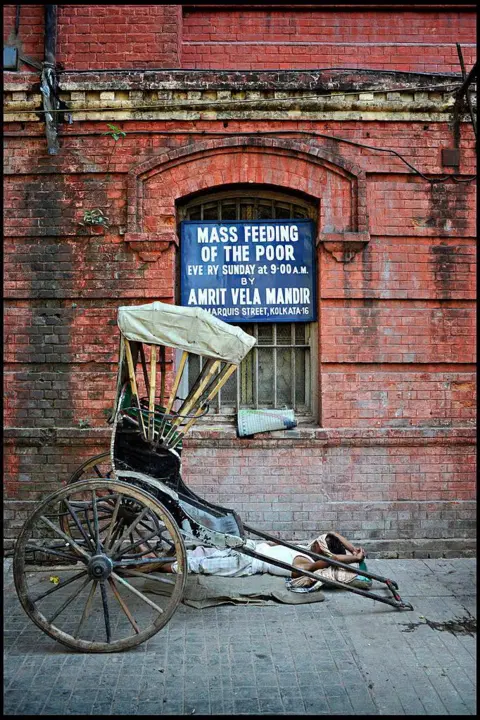

Much of the food given goes to communal free kitchens. Volunteering most commonly takes the form of service at religious institutions, including activities such as disaster relief organised by them.

“India is a very generous country. Our findings suggest that ordinary households play a much larger role than is commonly acknowledged. Generosity appears widespread and culturally embedded,” Jinny Uppal, head of Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy at Ashoka University, told the BBC.

The headline insight: Indian philanthropy is not elite-led but mass, local and relational – driven by faith, face-to-face appeals and everyday obligation, cutting across income levels.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The survey draws on more than 7,000 interviews across 20 states, spanning urban and rural India.

The analysis is anchored to India’s National Sample Survey (NSS) consumption data – a large, government-run household expenditure survey – to build income-segmented profiles of everyday givers. Respondents self-reported how often and how much they gave over a three-month recall period. The findings were then extrapolated to produce annual estimates.

The survey looks at “everyday giving” which includes both direct, personal help – to beggars, family or friends, often seen as charity – and donations to organised, non-religious institutions, which are typically described as philanthropy.

It also examines “retail giving”, typically defined as donations by ordinary individuals – not high-net-worth donors – to registered nonprofits. The survey adopts a broader lens, including informal, direct help to individuals as well as donations to religious institutions.

A lot of giving is shaped by proximity and faith, the survey found.

Roughly 40–45% of giving flows to religious organisations, with a comparable share directed to beggars and destitute people, especially in urban areas. In rural India, religious institutions take the lead.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

“We asked behavioural questions about motivation. For more than 90% of respondents, the underlying driver is a sense of religious duty – a moral obligation that shapes and sustains their giving,” says Krishanu Chakraborty, head of research at the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy at Ashoka University.

The most common way people encounter giving opportunities is in-person requests or canvassing – meaning direct appeals at homes, religious sites or public spaces, rather than digital campaigns or formal fundraising drives.

The survey found education correlates with generosity: donor participation peaks among graduates and postgraduates.

Yet, giving is not confined to the affluent. Even at low consumption levels (4,000–5,000 rupees per month), about half of households report giving; as incomes rise, participation climbs to 70–80%.

Gender patterns are subtle but telling: male-headed households are slightly more inclined toward religious giving, while female-headed households lean marginally toward supporting destitute individuals.

“The most important takeaway [of the survey] is that everyday generosity in India is systemic rather than sporadic,” Uppal says.

“It cuts across income groups, age, gender and urban/rural regions and is embedded in everyday social life.”

The second key takeaway: estimates suggest that everyday giving makes up about 15% of total giving in India, yet accounts for nearly a third of private donations to the organised social sector.

Getty Images

Getty Images

“Even with the small cheque size from everyday givers, this is a sizeable contribution from the citizenry towards social impact,” says Uppal.

The final takeaway, according to the researchers, is more methodological.

The survey responses were anchored to consumption data, allowing researchers to examine how spending patterns relate to giving. As household consumption rises, both participation in giving and the amount donated tend to increase, the survey found.

“India remains one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world and consumption is a major component of GDP. As household consumption expands over time, this segment of everyday giving is likely to evolve and potentially grow alongside it,” says Uppal.

In mature markets, everyday individual giving is the financial backbone of NGOs – formal, tracked and institutionalised.

In 2024, individuals gave $392bn in the US, accounting for 66% of all charitable donations. In the UK, public donations reached $20.7bn, with legacies and individual giving making up roughly 30% of charitable income.

This is not surprising, say experts. Across much of the Global South, person-to-person, informal giving often exceeds formal donations. In advanced economies, by contrast, giving is largely channelled to registered nonprofits – helped by tax incentives and older, more organised charitable sectors.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

The US Generosity Commission’s 2024 report noted an apparent decline in everyday giving. But it tracks only audited donations to registered nonprofits made through tax channels.

As giving shifts toward informal routes – online transfers, crowdfunding and other unaudited platforms – much of this behaviour goes uncaptured. Even in the US, the way people give is changing, experts believe.

In India, says Uppal, the “real headline” isn’t the percentage – it’s the breadth of participation.

The survey, she says, was conducted in March–April, months with relatively few religious events or festivals. “Given the high percent of giving to religious organisations, it is safe to assume that during other months with religious occasions, a larger percent of the population gives.”

In other words, in India generosity is possibly not a trickle from the top. It is a daily tide from below.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.