Hogging Your Wallet | Friends of Science

CLIMATE POLICY MEASURES – WHAT CANADIANS NEED TO KNOW, AND DON’T

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

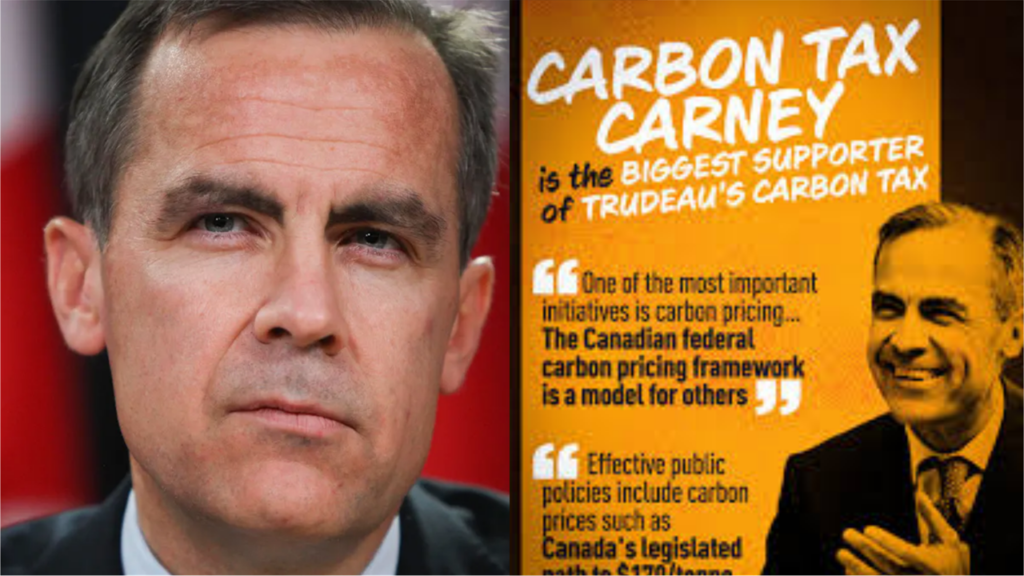

Much of the debate during the forthcoming national election campaign in Canada will focus on the fate of the “carbon tax”, but there are many more important climate policy issues that deserve attention. Given the prominence of the issue, it is surprising that the Canadian public has so little information about it. In this article, we will try to provide a partial review of the information that is now available and the information gaps that should be filled.

In December 2016, the federal and provincial governments jointly approved the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, with four “pillars”: pricing emissions; “complementary actions” where pricing faces market barriers or is insufficient to reduce emissions in the pre-2030 timeframe; adapting and building resiliency to climate change; and accelerating innovation and clean technology development.

Over the years, the number and range of both “carbon pricing “ (i.e. emissions taxation) and “complementary measures” at the federal, provincial and territorial government levels have steadily increased. In theory, the carbon pricing regimes remain central to the system (and have been the main focus of political debate) but in practice they have played a diminishing role.

In 2022, the Eighth National Communications Report and 5th Biennial Report on Climate Change listed 103 federal government measures and 319 provincial and territorial ones. The Canadian Climate Policy Partnership (C2P2), based at the University of Calgary produced a better, though still incomplete, policy/measures inventory that it frequently updates. The August 2024 version of the C2P2 inventory lists only 327 “policies”, 71 of which are federal government policies. The lack of agreement even on the number of measures leaves one wondering about both how the records are kept and why so many are needed.

A casual glance through the list of measures now in place makes obvious the degree of potential overlap and duplication among them. This makes it virtually impossible to determine the marginal effect of each new measure.

Fully half of the policies/measures identified by the C2P2 have no indication of what governments are spending on them. We have only isolated sources concerning the total costs of the measures. For example, in Budget 2022, the federal Liberal government stated that its expenditures over the period since it was elected (i.e. October 2025) were over $120 billion; in Budget 2023, it projected that expenditures over the remainder of the fiscal planning period (i.e. presumably 2023-2024 to 2027-2028) would probably be $121 billion. It provided no breakdown of these expenditures either by year or by measure.

The total federal and provincial expenditures on climate measures over the period 2020 to 2030 as listed by the Canadian Climate Institute are $476 billion, or $47.6 billion per year and $11,900 per resident of Canada over the decade. That includes just what had been announced up to mid-2024.

In July, 2024, The Fraser Institute published an analysis by Professor Ross McKitrick of the University of Guelph of the economic impact and GHG effects of the federal government’s 2022 Emissions Reduction Plan. In that plan the government committed to the target of reducing GHG emissions to at least 40 % below 2005 levels by 2030 (i.e. to 439 megatonnes). Professor McKitrick argued that the federal government exaggerated the costs to Canada of climate change and presented them in a “misleading and overstated way”. The government also over-stated the benefits of Canada’s emissions reductions. He estimated that unless one places an extremely high value on each tonne of emissions avoided, the costs of the Emissions Reduction Plan would greatly exceed the benefits.

It is notable, if surprising to many, that the last systematic effort by the federal and provincial governments in Canada to assess even prospectively the likely cost-effectiveness of emissions-reduction measures was that conducted during the “Climate Change Table Process” that occurred in 1998 and 1999. To this day, there has been no effort to redo the analysis. Instead, departments have essentially taken the approach that “any and all measures must be taken regardless of costs, as we are saving the planet”.

It may in fact be true that neither the governments nor the public really know what the “numbers” about climate policy measures really mean. But acknowledging the uncertainties, why is it so difficult to keep track of our collective expenditures in and paybacks from climate policy measures? The governmental machinery that is supposed to guarantee transparency and public accountability is there, but the results do not match the process. Democratically-elected governments hope to inspire public confidence. Yet this confidence is only inspired by honesty, transparency and accountability. Today climate policy in Canada offers none of these things.