Cuba’s tourism minister insists sector ‘alive and kicking’

Will GrantMexico, Central America and Cuba correspondent

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

When US President Barack Obama stepped off Air Force One onto Cuban soil in 2016, he was one of around four million visitors to the island that year.

A record high at the time, Cuba’s visitor numbers continued to grow until a high-water mark of almost five million people two years later.

Since then, however, the fall in Cuban tourism has been precipitous.

Battered by the twin effects of the coronavirus pandemic and harsher travel restrictions imposed by the Trump administration, last year was one of Cuba’s poorest for the industry this century.

With the island’s traditional industries – namely sugar, tobacco and nickel – in the doldrums, tourism is Cuba’s main source of foreign currency earnings after remittances.

Fewer tourists, then, means less money in the state coffers to invest in the island’s crumbling energy infrastructure, or to spend on urgently needed basic foods and medicine.

Traditional allies – Venezuela and Russia – are facing major economic challenges of their own, and while China has funded some solar power projects, Beijing is preoccupied with bigger geopolitical issues.

Today, Cuba is in the grip of its deepest economic crisis since the Cold War.

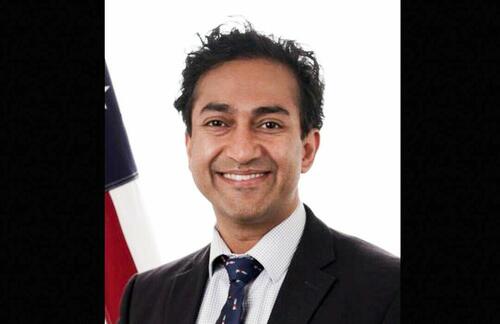

“Conceptually, tourism remains the country’s economic locomotive,” explains the Cuban tourism minister, Juan Carlos García Granda.

In Havana, the BBC asks the man at the wheel of that economic motor about the industry’s current state of health:

“Well, I’m not a doctor,” García Granda comments wryly, “but I can tell you that Cuban tourism is alive and kicking.”

He claims that the Cuban government has halted the slide seen in 2024, and that the second trimester of this year will show improved statistics.

“We face obstacles none of our competitors do,” García Granda continues.

“The intensity and the pressure from an economic war launched by the world’s main source of tourists, the United States, has prevented Cuban tourism from returning to pre-pandemic levels.”

Referring to the six decades-long US economic embargo on Cuba, García Granda says steps taken by Washington since President Trump’s first term in office in 2017 have been specifically designed to harm Cuba’s tourist trade.

“In Trump’s first term, they took 263 measures [against Cuba], the majority aimed at destroying Cuban tourism.”

In particular, he points to a ban on US cruise ship companies from docking in Cuban ports.

“Without that, we could have counted on another one-million tourists [a year]”, García Granda estimates.

A more draconian step came in January 2021 when the US again included Cuba on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism (SSOT). President Biden removed Cuba from the list in January of this year, only for Trump to add it again just days later when he started his second term.

The classification has a knock-on effect: UK and some European tourists who have visited Cuba after 12 January 2021 are no longer eligible for an ESTA (the Electronic System for Travel Authorisation) to enter the US.

Given the headaches for those travellers – of finding themselves plunged into a longer, more complex US visa process – many potential British visitors have been put off from visiting Cuba altogether.

“Thousands of British tourists must reach Cuba via Spain, via France, some even via Canada. Yet not through Miami. Explain to me why a Brit, completely free, can’t travel to Cuba via Miami?” García Granda asks rhetorically.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Yet not all the decisions affecting the health of Cuban tourism have been taken in Washington. During the Obama-era thaw, the Cuban government instigated an ambitious hotel-building programme in Havana and the main beach resort, Varadero.

In the capital alone, at least half a dozen new five-star hotels have been erected to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. The latest, known locally as the Torre K, is the tallest building on the island, its imposing structure towering over the Vedado district of the Cuban capital.

“There are plenty of other hotels in Havana and it doesn’t fit in with its surroundings,” says student Danais, speaking in the plaza opposite. “I’d have used the money for other ends, for things we really need like dealing with the blackouts.”

“It doesn’t respect its urban context,” echoes Sabrina, who is studying architecture. “As an architect, I see some positive and negative points, and it’s certainly one of the most impressive buildings in the country.

“But it didn’t need to be so opulent and extravagant, especially with so many hotels in the city lying empty.”

I put those points to the tourism minister, saying most Cubans do not see the Torre K as a monument to the country’s ingenuity and innovation, but rather as a symbol of poor central planning and the government’s failure to listen to the most pressing needs of its people.

García Granda acknowledges that the hotel has its critics, but argues that plenty of Cubans, particularly those who work there, appreciate the new addition to the Havana skyline.

Nevertheless, Cuba’s hotel construction push raises a key question over whether Cuba was misled by the Obama administration – sold a vision of warmer political ties and a steady flow of US visitors which never materialised.

Was the Cuban government guilty of failing to plan for changing political seas, or is Washington at fault for implementing a foreign policy which was not sufficiently robust or durable to last from one administration to the next?

Unsurprisingly, the minister insists that Cuba’s tourism strategy was not predicated on poor planning.

“A gap” in hotel provision in Cuba was revealed “during the Obama era, which showed the need for more accommodation in Havana”, he argues. Furthermore, he adds, the costs have not solely been shouldered by the Cuban state.

“More than 70% of Cuban tourism is based in foreign investment, there are more than 19 international companies based here to attract tourism to Cuba.”

Surely, I ask, the government can appreciate the frustrations of people on the streets when, in the darkness of a nationwide blackout, they pass a new 200-million-dollar hotel in Havana with its lights blazing?

Little wonder many are asking why those funds have not been directly invested into the Soviet-era energy infrastructure which so sorely needs it.

“The people aren’t frustrated,” Mr García Granda retorts. “Yes, there may be some indignation on the streets, but they’re still here. They’re still fighting, still working, still trying to help.”

Thrusting a graph into my hands showing green shoots of improvement in terms of UK visitor numbers since Covid, he remains defiant that better times are on the horizon:

“We are going to fill the hotels,” he insists. “We are going to get out of this economic situation and tourism will play its part.”

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.