Could Cardinal Prevost be the first American pope? – LifeSite

Tue May 6, 2025 – 11:19 am EDTTue May 6, 2025 – 2:37 pm EDT

Why this piece is important:

Prevost is being seriously considered as a papal candidate—but questions surround his silence and his actions as Prefect for the Dicastery of Bishops.

The big picture:

Prevost has cooperated in advancing Francis’ agenda, facilitated the appointment of heterodox bishops throughout the world, and tacitly denied the traditional teaching on the episcopate.

Flashpoint:

He oversaw the deposition of the most conservative U.S. bishop (Strickland) and the appointment of a notorious liberal to one of the most prominent diocesan see (McElroy).

Takeaway:

Prevost has remained silent in the face of the great doctrinal questions of our day, and facilitated the longest-lasting legacy of Francis’ reign.

(LifeSiteNews) — Seemingly out of nowhere, Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost is being discussed as a serious candidate in the upcoming conclave.

Prevost, born in Chicago and having spent decades in Peru, has risen through the ranks without attracting public prominence—until now. He is currently the Prefect of the Dicastery of Bishops: The Pillar claims that “Prevost saw his task as that of identifying men who embodied Pope Francis’ ideals for bishops.”

He is being lauded as a candidate of discretion, administrative experience, and balance. La Croix International has described him as “a bridge between factions,” noting that “Prevost has avoided the ideological battles that have flared during the final years of Francis’ pontificate.” Because of this, he might seem to represent a “clean image” and a new start.

But who is Prevost, and could he be elected as the first American Pope?

Prevost’s formation

Prevost was born in 1955, and entered the Order of St. Augustine in 1977 (taking his solemn vows in 1981). Soon after ordination in 1982, he joined the Peruvian Mission, and began a decades-long career in Latin American ecclesial affairs.

In 2014, Francis made him the Apostolic Administrator of the Peruvian Diocese of Chiclayo, and he received his episcopal ordination at the hands of Bishop James Green soon after. In 2015 he was made the bishop of Chiclayo.

In 2020, Francis named him as a member of the congregation of bishops, and in January 2023, he made him the Prefect of this congregation (now a dicastery). Francis made him a cardinal nine months later. In addition to the dicastery of bishops, he is a member of seven other dicasteries, including that of Evangelization and of the Doctrine of the Faith—indicating the trust and appreciation Francis had in Prevost, according to Pentin and Montagna.

Silence and ambiguity on grave issues

Prevost is praised by many parties for his discretion. John L. Allen Jr describes his appearance as “a moderate, balanced figure, known for solid judgment and a keen capacity to listen, and someone who doesn’t need to pound his chest to be heard.”

While this may be valued by the other American prelates to whom Allen refers—and even by Cardinal Electors—such “discretion” comes at the cost of having remained silent when there was a grave duty to profess the faith.

The external profession of the faith is not just a condition of membership of the Church (and thus of holding office or being elected to any office). It is also a strict obligation on all Catholics “whenever their silence, evasiveness, or manner of acting encompasses an implied denial of the faith, contempt for religion, injury to God, or scandal for a neighbor.”[1]

This is an established principle, expressed by Canon Law, St. Thomas Aquinas, saints, doctors, theologians and moralists, and the duty only increases the higher one’s rank in the Church.

Another basic principle is that “silence implies consent”—in other words, if one is silent in the face of doctrinal error, one is presumed to accept it. This is why Pope Felix III wrote:

An error which is not resisted is approved; a truth which is not defended is suppressed… He who does not oppose an evident crime is open to the suspicion of secret complicity.[2]

Regarding the great controversies of Francis’ pontificate, Prevost has no known response on the issues raised by Fiducia Supplicans or Amoris Laetitia. Thus, the “discretion” that might attract votes from other cardinals seems rather to be a failure to witness to Christ, and even a tacit endorsement of the errors in question.

This is why, in this context, cowardice and imprudent discretion would not just constitute moral faults, but would have wider and more serious implications on Prevost’s membership of the Church and eligibility for the papacy.

This tacit endorsement necessarily continues unless and until Prevost counteracts it through professing the faith clearly on the disputed questions.

What it means for Prevost to be Prefect of the Dicastery of Bishops

Francis’ episcopal appointments will be among the longest-lasting effects of his reign. Prevost has been intimately involved in facilitating this legacy.

His position as Prefect of the Dicastery of Bishops means that, after Francis, he has been responsible for the selection and appointment of Latin rite bishops, as well as administering “problem cases.”

Although Prevost has not been forthright about the key issues facing Catholics in our time, the discharge of his role as Prefect may reveal much about his thoughts.

For instance, Prevost has praised what Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli referred to as “one of the novelties” Francis introduced by appointing three women to the Dicastery, referring to the “enrichment” and “important contribution” they have offered to the process of selecting and appointing bishops. Even if this is considered inoffensive in itself, the general push for the greater involvement of women is linked, for many powerful persons, with a push for female ordination to the diaconate or other orders.

Even more clarity appears when we consider the appointments and cases administered under Prevost’s tenure as Prefect.

For instance, in February 2023, early in his tenure as Prefect, the Dicastery announced the Apostolic Visitation of the diocese of Fréjus-Toulon, France—ending ultimately in the departure of Bishop Dominique Rey.

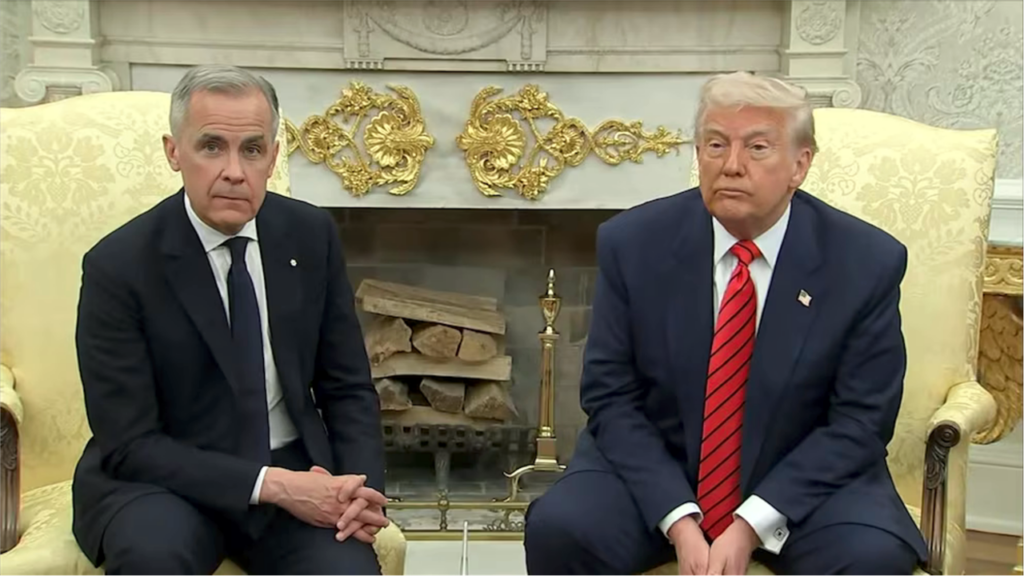

This becomes even clearer when we consider two contrasting cases in the U.S. First, Prevost was Prefect when the notoriously liberal Bishop Robert W. McElroy was appointed Archbishop of Washington in January 2025.

Second, Prevost was Prefect in 2023, when the Dicastery undertook a visitation of the diocese of Tyler, Texas. This ended in the Dicastery asking Bishop Strickland to resign, before he was ultimately removed by Francis.

In short, Prevost was the Prefect of the Dicastery which enabled the appointment of a notorious liberal to one of the most prominent positions in the U.S., and the deposition of the most prominent conservative in the U.S.

It is true that the final decisions and responsibility for all such appointments and administration lay with Francis; but once again, silence implies consent. There is no warrant for assuming that Prevost has only carried out these actions under protest or against his better judgment. In any case, continuing in his role rather than resigning, Prevost signals that he believes such appointments and decisions are at least tolerable. This recalls St. Roert Bellarmine’s words:

[M]en are not bound, or able to read hearts; but when they see that someone is a heretic by his external works, they judge him to be a heretic pure and simple, and condemn him as a heretic.[3]

Let us consider Prevost’s “external works” further, to see what they reveal.

What sort of bishops has Prevost been helping to appoint?

As mentioned above, The Pillar claims that “Prevost saw his task as that of identifying men who embodied Pope Francis’ ideals for bishops.”

Andrea Tornielli asked him to identify the characteristic profile of the bishops he is appointing,[4] and he summarized it with reference to Francis’ ideas of “closeness.”

He makes much of a bishop’s role in promoting unity, both with the Church and with the Roman Pontiff. He writes:

The bishop is called to this charism, to live the spirit of communion, to promote unity in the Church, unity with the Pope. This also means being Catholic, because without Peter, where is the Church? Jesus prayed for this at the Last Supper, ‘That all may be one,’ and it is this unity that we wish to see in the Church.

He treats unity as something lacking in the Church “that we wish to see,” which appears to be a tacit denial of the defined dogma that the Church “necessarily and indefectibly is One”—that is, united in faith, government and worship.[5] Pope Pius XI also rejected and refuted the idea that Our Lord “merely expressed a desire and prayer, which still lacks its fulfillment”:

And here it seems opportune to expound and to refute a certain false opinion […] For authors who favor this view are accustomed, times almost without number, to bring forward these words of Christ […] For they are of the opinion that the unity of faith and government, which is a note of the one true Church of Christ, has hardly up to the present time existed, and does not to-day exist.[6]

The Church is perpetually united in herself: the bishop’s role is to ensure that his flock remains united to her, but the Church is not disunited by virtue of those who have fallen away from her. Such an idea represents a fundamentally non-Catholic ecclesiology.

Further, the communion, charity and social unity Prevost discusses make up only one “bond of unity” for which the bishop is responsible.

Prevost minimizes the importance of doctrine and the bond of faith

Vatican I makes clear that Christ willed that “there should be shepherds and teachers until the end of time” not just to secure the bond of social unity and communion, but also of faith.[7]

This is the meaning behind the foundational text on the duties of bishops, found in the Epistle to Titus in Holy Scripture, which places great emphasis on doctrine:

Embracing that faithful word which is according to doctrine, that he may be able to exhort in sound doctrine and to convince the gainsayers.

For there are also many disobedient, vain talkers and seducers: especially they who are of the circumcision. Who must be reproved, who subvert whole houses, teaching things which they ought not, for filthy lucre’s sake. […] Wherefore, rebuke them sharply, that they may be sound in the faith: Not giving heed to Jewish fables and commandments of men who turn themselves away from the truth.

But speak thou the things that become sound doctrine […] In all things shew thyself an example of good works, in doctrine, in integrity, in gravity (Titus 1.7, 9-11, 14, 2.1, 7)

St. Paul then goes on to command Titus to avoid heretics whose obstinacy is demonstrated, “knowing that he that is such a one is subverted and sinneth, being condemned by his own judgment.” (Titus 3.11) The Didache also emphasizes the importance of bishops as “prophets and teachers.” (Chapter XV)

Despite this apostolic emphasis, Prevost seriously minimizes and even dismisses the importance of doctrine and the faith. He portrays a concern for doctrinal truth as “division and polemics”:

Divisions and polemics in the Church do not help anything. We bishops especially must accelerate this movement towards unity, towards communion in the Church.

He creates a false dichotomy between doctrine and loving Christ:

We are often preoccupied with teaching doctrine, the way of living our faith, but we risk forgetting that our first task is to teach what it means to know Jesus Christ and to bear witness to our closeness to the Lord. This comes first: to communicate the beauty of the faith, the beauty and joy of knowing Jesus. It means that we ourselves are living it and sharing this experience.

This is a very distorted way of framing the situation and suggests a clear agenda to minimize the importance of doctrine.

- First, Prevost ignores that Christ’s doctrine is how we come to know him, since we cannot have charity without faith.

- Second, because of this dependence, it is wrong to suggest that there is an opposition between doctrine and love.

- Third, there is no contemporary “preoccupation” with doctrine, at risk of overshadowing “knowing Christ.” Such a suggestion is ludicrous.

In an age defined by doctrinal collapse, accelerated by his late master Francis, Prevost is engaging in gaslighting, and the effect is the further minimization of the importance of doctrine.

Synodality and the rejection of episcopal authority

Prevost has also spoken favorably of Francis’ concept of “synodality.” Christopher White of the National Catholic Reporter claims that Prevost “has been a vocal proponent of Francis’ emphasis on synodality.” He also claims that, in a 2023 interview, Prevost suggested that “synodality” is the solution to “the current polarization currently gripping the Church.”

However, when asked about “synodality” in that interview, he was dismissive of those who were concerned “because they do not understand where the Church is going”

Perhaps they prefer the security of answers already experienced in the past.

He added, clarifying what “synodality” meant for the bishops:

The episcopal ministry performs an important service, but then we must put all this at the service of the Church in this synodal spirit that simply means walking together, all of us, and seeking together what the Lord is asking of us, in this our time.

Service is key to Prevost’s ideas about the episcopate. However, his understanding of how the episcopacy serves the Church represents a significant departure from the Church’s doctrine; and this departure is justified by synodality.

The traditional understanding holds that the bishop is the ecclesiastical authority of his diocese, responsible for teaching, sanctifying and governing the flock appointed to him by the Roman Pontiff. He possesses ordinary jurisdiction over his diocese, in a way that is complete in its kind, whilst also being dependent on the Roman Pontiff.

This is all undermined by “synodality,” a concept, inspired by the modernism condemned by Pope St Pius X, in which the Church’s doctrine is subjected to the evolving “experience” and “discernment” of the community—rather than received from divine revelation and preserved by the Church’s magisterium. It necessarily undermines the divinely instituted role of the bishop by recasting him as a facilitator of communal dialogue, subordinating him to “discernment” and shifting his duty to managing consensus and a naturalistic concept of “service.”

This is what we find in Prevost’s understanding of the role of the bishop—a concerning sign, given his oversight of episcopal appointments.

Prevost’s rejection of bishops as ‘princes’ contradicts Catholic tradition

Prevost emphasizes the bishop’s role as pastor or shepherd, but he presents a shepherd without a rod or a staff. He talks of “an idea of authority that no longer makes sense today,” which signals his departure from the traditional teaching, even while retaining some of the terminology. In a short video, he said:

And as Pope Francis has reminded us many times: A bishop is called to serve. His authority is service. And so to look for different ways in which a bishop can serve in any given society, in any given church, I think is very important.

The bishop is not supposed to be a little prince sitting in his kingdom, but rather called authentically to be humble, to be close to the people he serves, to walk with them, to suffer with them, and to look for ways that he can better live the Gospel message in the midst of his people.

On the contrary, the diocesan bishop is indeed a “prince” in his diocese. The word is derived from the Latin princeps, which indicates the first, foremost or chief person. This is precisely what the bishop is. In his encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi, Pius XII repeats this traditional teaching, and adds:

[Catholics] are ruled by Jesus Christ through the voice of their respective Bishops. Consequently, Bishops must be considered as the more illustrious members of the Universal Church, for they are united by a very special bond to the divine Head of the whole Body and so are rightly called ‘principal parts of the members of the Lord.’[8]

The Roman Liturgy specifically refers to bishops as “princes,” and attributes to them other royal language. The following text referring to their principality occurs throughout the liturgical texts for several feasts of the Apostles, sometimes on multiple occasions in each Mass:

To thy friends, O God, are made exceedingly honourable: their principality is exceedingly strengthened. (Ps. 138.17)

The same theme appears in other liturgical texts for the Apostles:

May the Lord place him with the princes of his people (Ant. 2, Second Vespers of Apostles)

Thou shalt make them princes over all the earth. (Offertory, St Barnabas, classed as an Apostle by the Missal)[9]

Nor are such texts limited to the Apostles: they also appear in the liturgical texts of the successors of the apostles, namely the bishops:

The Lord made to him a covenant of peace, and made him a prince; that the dignity of the priesthood should be to him forever. (Introit for the Mass Statuit, of a Bishop)[10]

As is well established, the law of prayer determines the law of belief. Further, these texts cannot be understood as referring to a principality in the world to come: they convey the authority and principality of the Apostles and their successors in this life, and they have been sought out by the fathers of the Roman Liturgy for this very purpose.

Prevost’s false dichotomy between the principality and service is to neuter the example of service set by Christ, particularly set at the Last Supper—at which he did not deny that he was the Master:

You call me Master and Lord. And you say well: for so I am. (John 13.13)

While he may also be expected to excel in the corporal works of mercy and, indeed, in accompanying the suffering members of his flock, the bishop serves in the most important way by discharging his office of teaching, ruling and sanctifying his flock. In doing so, he gives his flock not merely natural goods, but supernatural goods and Christ himself. To take the words of the Gospel about service and humility and to use them to minimize or destroy the mission he has been given by divine right is fundamentally unsound.

We should be concerned that the man responsible for selecting bishops has such a naturalistic and egalitarian conception of the episcopate. This may go some way to explaining how and why Prevost’s conscience could allow him to remain in post while heretics are selected for diocesan sees, and while men such as Bishop Strickland are removed.

‘Service,’ arbitrary authority and abuse cases

Francis’ emphasis on service and inclusion was not straightforward: he showed himself more than willing to exercise power over Catholics, often in the most arbitrary and lawless ways. The emphasis on service and accompaniment, and the pretended rejection of authority (including the external trappings of office) was simply a cover for rejecting doctrinal clarity.

Some of Francis’ bishops have followed the example of their master. Sometimes, this manifests itself through an arbitrary and lawless approach, which extends even to matters of safeguarding. Unfortunately, this is alleged to be the case with Prevost. The Pillar reports the following:

In 1999, he was elected provincial prior of the Midwest Augustinians. A year into the role, he permitted a priest who sexually abused minors to live in a Chicago rectory half a block from a Catholic school, at the archdiocese’s request.

When The Pillar reported on this in 2021, “Prevost could not be reached for comment.” The Pillar also noted an uncanny association with Cardinal Blasé Cupich:

In an unusual twist, Prevost is not the only member of the Congregation for Bishops to permit a priest accused of sexually abusing a minor to reside at the same Augustinian house in Chicago. In 2018, Cardinal Blase Cupich, also a member of the congregation, apologized for allowing a different priest accused of sexual abuse to live in the very same house, apparently, Cupich said, because of a miscommunication.

The Pillar also notes:

Individuals in the Chiclayo diocese would later accuse Prevost of failing in 2022 to open an investigation into their accusations of abuse against two priests [beginning in 1997].

In March 2025, SNAP (Survivors Network of these Abused by Priests) appealed to Rome, alleging:

… that under the leadership of Cardinal Prevost, the Diocese of Chiclayo did not investigate their abuse claims and misrepresented [the alleged victims’] testimony in the report to the DDF, preventing an accurate assessment of the case.

Cindy Wooden reports:

[Prevost] personally met with the victims in April 2022, removed the priest from his parish, suspended him from ministry and conducted a local investigation that was then forwarded to the Vatican. The Vatican said there was insufficient evidence to proceed, as did the local prosecutor’s office.

The Pillar noted that “[t]he diocese vigorously denied the claim when the cases made international headlines in 2024,” and claims that Prevost acted appropriately. However, as is clear, there remain unanswered questions about the transparency and speed.

Conclusion: Can Prevost be elected?

The Catholic Church teaches that any candidate for the papacy (or any other office) must be:

- Male

- In possession of the use of reason

- A member of the Catholic Church

Regarding the third criterion, the Church also teaches that her members are only those who (a) are validly baptized, (b) publicly profess the Catholic faith, and (c) are united to the body and subject to the legitimate hierarchy.

In this piece, we have seen that Prevost has:

- Conspicuously failed to profess the faith in relation to the grave threats to faith and morals in our day—to the point in which this silence is taken as “discretion” and counted in his favor as a candidate

- Indicated the state of his mind through his cooperation with the appointment of notorious liberals and the deposition of conservatives

- Cooperated in the consolidation of Francis’ longest-lasting legacy, namely the appointment of bishops embodying his ideals

- Implicitly denied the dogma of the Church’s visible unity, by casting it in the terms rejected and refuted by Pope Pius XI in Mortalium Animos

- Minimized the importance of doctrine in the role of the bishop, contrary to Sacred Scripture, Apostolic Tradition and the general sense of theology

- Dismissed those who “prefer the security of answers already experienced in the past”

- Promoted the modernist idea of “synodality” in such a way as to destroy the traditional concept of the bishop’s threefold power of teaching, ruling and sanctifying his flock

- Explicitly denied that a bishop is a “prince” in his diocese, contrary to the teaching of the magisterium and the liturgy

- Replaced the traditional understanding of the bishop’s role with that of “service,” presented in naturalistic terms, and which he has already separated from doctrine and governance through his other words (even while he retains references to teaching and shepherding).

If we were limited to the matter of his silence, we might be able to excuse Prevost on the grounds of cowardice or tactical cunning—neither of which present him as a good candidate for the papacy. The Church does not need cowards or tacticians: she needs men who take seriously the words of St. Paul to the Galatians:

But though we, or an angel from heaven, preach a gospel to you besides that which we have preached to you, let him be anathema.

As we said before, so now I say again: If any one preach to you a gospel, besides that which you have received, let him be anathema.

For do I now persuade men, or God? Or do I seek to please men? If I yet pleased men, I should not be the servant of Christ. (Gal. 1.8-10)

She needs bishops who will boldly obey the exhortation of St Paul to Timothy:

I charge thee, before God and Jesus Christ, who shall judge the living and the dead, by his coming and his kingdom:

Preach the word: be instant in season, out of season: reprove, entreat, rebuke in all patience and doctrine.

For there shall be a time when they will not endure sound doctrine but, according to their own desires, they will heap to themselves teachers having itching ears: And will indeed turn away their hearing from the truth, but will be turned unto fables.

But be thou vigilant, labour in all things, do the work of an evangelist, fulfil thy ministry. (2 Timothy 4.1-5)

A man who has remained “discreet” during the last few years—and indeed been promoted in that time—seems unlikely to be suitable.

However, the wider points discussed in this article—doctrinal deviations which become clear after a careful consideration of his role as Prefect for the Dicastery of Bishops—are both cause for alarm in themselves, and as shedding light on his silence. They indicate that Prevost is not a coward or a tactician, but a loyal son of Francis, and that he will continue the work of his master and benefactor, if he is elected—even if he does so in a more discreet and moderate way.

This raises grave questions about whether or not Prevost can be said to profess the Catholic faith at all, and thus whether he is a member of the Church. If he is not a member of the Church, then it is not possible for him to be validly elected as pope.

At the very least, there is serious doubt on the matter: and a man whose visible membership in the Church is itself in serious doubt can only be doubtfully elected to the papacy, even if the conclave is unanimous. Should such a man be elected, the resulting doubt would not be about his popularity or policies, but about his very authority. This is why great theologians and canonists held that a doubtful pope is no pope at all.

Needless to say, these points have implications that extend beyond just Prevost, applying also to those other cardinals who have been “discreet” and “moderate” in the face of Francis’ doctrinal aberrations. It is not enough to ask whether a man is prudent, discreet, or personally sincere. The question is whether he professes the faith whole and entire, in public and without compromise. If the answer is not a clear “Yes,” then the conclusion is clear: he cannot be validly elected or accepted as pope.