Cochrane on a Suicide Mission

The Cochrane Collaboration publishes systematic reviews of healthcare interventions in the Cochrane Library. It was once a highly respected institution, but this has changed, and I shall tell a particularly grotesque story about Cochrane bureaucracy, protection of guild and financial interests, inefficiency, incompetence, censorship, and political expediency, which I consider the beginning of the end for Cochrane.

As the events have lasting historical interest, I have uploaded and referenced the documents we received from Cochrane and our replies when we tried to update our published Cochrane review of mammography screening with additional mortality data.

Background

In 1999, after Sweden had screened for breast cancer for 14 years, a study failed to find an effect on breast cancer mortality.1 This led the Danish Board of Health to ask me to review the randomised trials. My statistician, Ole Olsen, and I were astonished when we realised that the evidence for the benefit of screening was poor and that screening might do more harm than good because of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of harmless cell changes and cancers, which increase mortality.

We noted in our report that, in contrast to what was claimed, screening had not led to less but increased use of radical treatments including mastectomies because of an overdiagnosis rate of 25-35%. We also noted that screening did not reduce all-cause mortality.

We delivered our report a week before the Danish parliament would vote about introducing screening but the director of the Board of Health, Einar Krag, censured our report and ensured that the minister, who was against screening, did not get it before the voting.2,3

In Krag’s view, Danes were not entitled to learn about our findings. My view was that the whole world should know about them, and we published our results in the Lancet, in January 2000.4 Our paper created a media storm and immense furore among screening advocates.3

Lancet’s editor Richard Horton noted that the editors of the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group had disowned our work,5 pointing out that our review was not a Cochrane review and had not been reviewed by them.6 What’s the problem with that? Lancet is not an inferior journal.

Cochrane Steering Group co-chair Jim Neilson complained that our review gave the impression that it was a Cochrane review.7 It obviously didn’t, as it was not published in the Cochrane Library and did not even look like a Cochrane review. What had happened was that some staunch screening advocates went ballistic about our results and complained to Cochrane without providing any scientific arguments.

The 2001 Cochrane Review Scandal

The Board of Health funded us to do a Cochrane review but tried to interfere with our work in the most absurd ways to ensure that we arrived at politically correct results.2,3 And when we submitted our review to the Australian-based Cochrane Breast Cancer Group – which had a financial conflict of interest, as it was funded by the centre that offered breast screening in Australia – we ran into a roadblock. The editors refused flatly to include data on the most important harms of screening, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment of healthy women, even though these outcomes were listed in our protocol the group had accepted and published. We wasted a lot of time negotiating with the group but got nowhere.

It was the biggest scandal in Cochrane’s history at the time.2,3 As we considered it more important to inform women honestly than to protect Cochrane guild and financial interests, we sent the full review, including the harms, to the Lancet. Horton worked with record speed and ensured that our review came out in the Lancet8,9 at the same time as the stymied review appeared in the Cochrane Library.10 One of the Cochrane editors, John Simes, said to Horton that we had agreed to the changes they had insisted on, but I provided Horton with internal emails to demonstrate that Simes was lying. Horton then wrote a scathing editorial about the affair that was very harmful for Cochrane’s reputation.5

It took me five years, with repeated complaints to the Cochrane Steering Group and Cochrane arbiters before we were allowed to add the harms of screening to our Cochrane review.2,3,11

Cochrane Rejected the Fourth Update of our Cochrane Review for no Good Reason

I updated the Cochrane review again in 200912 and 2013.13 This was uneventful. But when, in January 2023, I had added more deaths that had been published in two of the best trials, I anticipated big problems with Cochrane censorship, and a very slow editorial process, because of my previous experiences with Cochrane.7 I therefore published the more extensive data after my co-author had checked them in May 2023 on my website in the public interest:14

The updated mortality data show even more clearly than before that mammography screening does not save lives. Breast cancer mortality is an unreliable outcome that is biased in favour of screening, mainly because of differential misclassification of cause of death. We therefore need to look at total cancer mortality and total mortality instead. The trials with adequate randomisation did not find an effect of screening on total cancer mortality, including breast cancer (risk ratio 1.00, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.04). All-cause mortality was not significantly reduced either (risk ratio 1.01, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.04).

My concerns about Cochrane processes were justified. After we had submitted our updated Cochrane review, it took six months before we got any feedback, in February 2024. The peer reviews we received – from 11 people, 8 of whom were from Cochrane – were excessive, with 91 separate points spanning over 21 pages that required our response.15

We were told that major revisions were needed; that only one round of major revisions was permitted; and that our review would be rejected if major revisions were still required. This was an easy way for Cochrane to bury reviews that threatened prevailing dogma or guild or financial interests: Just say a major revision is needed.

We questioned why a major revision was even required since we had merely submitted an update with more deaths of a review published four times earlier and were highly experienced scientists. My doctoral thesis was about meta-analysis;7 I have published 19 Cochrane reviews; have contributed substantially to developing the methods used in Cochrane reviews; have been an editor in the Cochrane Methodology Review Group for 17 years; have published guidelines for good reporting of systematic reviews (PRISMA);16,17 and became professor of clinical research design and analysis at the University of Copenhagen because of my methodological expertise.

We responded to the peer reviews18 and submitted a revised version. Three months later, we informed Liz Bickerdike, Senior Managing Editor, Central Editorial Service, that, given the rapidly evolving situation in this area where two major guideline groups, the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, had issued conflicting recommendations within the past month, we found it very important for an informed debate that our updated review was made available to the public and to decision-makers. We had therefore decided to upload the review, amended as per the review comments, to a preprint server.

Bickerdike was unhappy with this: “Cochrane does not currently have a specific preprint policy, and as such, we advise authors not to upload preprints of unpublished reviews to online preprint servers.”

We responded that several other updates of Cochrane reviews had been prepublished and uploaded our review.19 On 7 June 2024, I tweeted:

Screening for breast cancer with mammography has been sold to the public with the claims that it saves lives and saves breasts. It does neither and increases mastectomies. In the public interest, we have uploaded our updated review as a preprint https://bit.ly/4c6r9K7.

This was much appreciated outside Cochrane. During the first two days, over 50,000 people saw my tweet. As of today, half a million have seen it.

We thought there couldn’t be any more issues with our updated review, but three months later, we were shocked. We received 34 pages of comments, divided on 38 points.20

This was ominous and several of the comments were insane. This was not the Cochrane Collaboration I co-founded in 1993 where we helped authors get even poor reviews in shape instead of rejecting them after having raised insurmountable barriers. This, I also experienced when Cochrane rejected my protocol about withdrawing antidepressant drugs in patients who wished to come off them.21 Instead, Cochrane published a poor-quality review of withdrawal that was filled with industry-type marketing messages about how good the drugs were.21

It was an aggravating factor that some of the peer-reviewers didn’t understand the basics of cancer screening or review methodology, which unfortunately, didn’t prevent them from demanding ludicrous changes to our review.2 My wife, Helle Krogh Johansen, who is a professor of clinical microbiology, has co-authored 8 of my Cochrane reviews, and she declared many years ago that Cochrane is the amateurs’ paradise. Indeed, it is.

We submitted our reply to the peer-reviewers22 and the updated review.23 One of the things the editors required, with reference to the Cochrane Handbook,24 was that we should write that screening “may show little or no difference in terms of a reduction in breast cancer mortality.” This is silly, as it is subjective whether a difference is small or not. Moreover, there was no statistically significant reduction in breast cancer mortality in the reliable trials, those with adequate randomisation.19

On 20 February 2025, I wrote to Bickerdike:

Three months have now passed since we uploaded our revised review and replied to the peer review comments. A bit much, I think, given that our review has been around since 2001 and has been updated several times before, and that there were very little new data.

It should not take that long. The slowness of Cochrane was a major reason why all funding of the UK groups disappeared in 2023. I realise this has made it more difficult for Cochrane but believe the organisation should therefore have become far less bureaucratic, but I can see that it hasn’t.

The amount of comments we have received and needed to reply to has been excessive and caused us a lot of unproductive work. I co-founded Cochrane in 1993. This is not the Cochrane we created. It was far more effective in the old days.

Could you please accept our update now and get it published? And tell Cochrane leaders they need to apply lean principles?

On 26 February, six days after I wrote to Bickerdike, our update was rejected, which we had come to expect although we had done our utmost to meet all the unwarranted demands. She enclosed some comments25 but noted they were not exhaustive – even though they took up 62 pages! – and that we should not respond to them.

We were told we could appeal this decision, which we did on 24 March, over 9 pages with 5 attachments.26 Not because we expected the rejection to be overturned but because the whole affair was so absurd that we wanted to see how Cochrane would react to our evidence-based arguments.

One of the most important absurdities was that we were not allowed to call overdiagnosis what it was: overdiagnosis. Other reviews of breast cancer screening, official announcements from authorities, and Cochrane reviews of other cancer screenings had all done so, e.g. for lung cancer, prostate cancer and our own review of screening for malignant melanoma.27

We also noted that Cochrane’s editor-in-chief had used the term overdiagnosis; that major guideline groups used it for the incidence increases in relevant trials just as we had done; and that it was an official Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term used in the research database PubMed to describe the most important harm of screening.

We mentioned that we were surprised that the editors had demanded changes and deletions of text and assessments that were unchanged from the previous, extensively peer-reviewed versions of our review, and that the line between editing and censoring might have been crossed.

We explained that editors did not need to agree with the judgments and interpretations of the authors, and that it would be a threat to academic freedom, debate, and progress if Cochrane editors acted as judges of opinion. On top of this, no one in the whole world had studied all the evidence relevant for our review in such detail as I and my various co-authors had, which included protocols and other reports in Swedish. That we were the top experts in this matter was not respected by Cochrane, which clearly had a political agenda, to defend mammography screening.

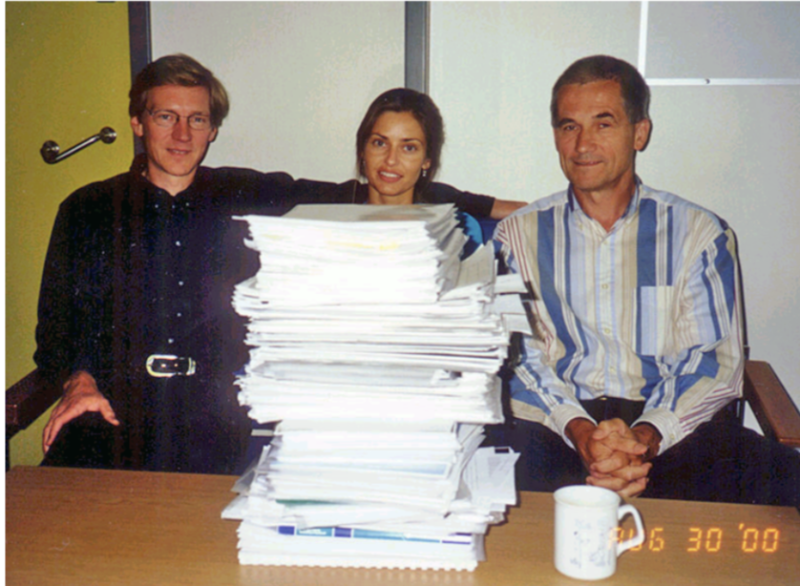

forty centimetres of literature? (Ole Olsen, Tine Bjulf and Peter Gøtzsche)

The ”Sign-Off Editor” noted that our review might create a potentially damaging firestorm of misinformation. This was blatantly false. We believe our review of breast screening is the most unbiased and comprehensive one that exists but we were not allowed to present the results as they were even though everything we wrote was based on solid science and had appeared in earlier versions of the review.

This was outright editorial misconduct and censorship, protecting the interests of those colleagues who advocated breast screening and denied its lack of a mortality benefit and its obvious and substantial harms.

We noted in our appeal that already the first version of our review, from 2001, had a section in the Discussion about “False positive diagnoses, psychological distress and pain,” but the editors denied us the possibility to include such information even though it is very important for the women’s decision-making.

We concluded in the abstract that “Breast screening does not meet the criterium that population screening should be based on rigorously performed randomised trials that show that the benefits outweigh the harms” and that “Women, clinicians and policy makers should consider the trade-offs and the uncertainties of the evidence carefully when they decide whether or not to attend or provide breast screening programmes.” The Sign-Off Editor argued that we went too far and that our “discussion is not balanced and based on the evidence but has pre-conceived ideas of direction i.e. no benefit of screening, rather than considering it may actually have benefit not detected.”

It is shameful that Cochrane argues this way. Advocates of alternative medicine also argue that their remedies might have benefits not yet detected, which is what we call wishful thinking. Furthermore, we had no pre-conceived ideas about the effect when we did the first Cochrane review2,3 and our discussion was balanced.

We noted in our appeal that, according to the UK National Screening Committee, a criterium for the introduction of screening is that “There should be evidence from high quality randomised controlled trials that the screening programme is effective in reducing mortality or morbidity.”28 Since breast screening does not reduce mortality and increases morbidity, our recommendation regarding whether a screening programme should be provided was actually much too kind. I have argued elsewhere that screening should be abandoned because it is harmful.29

On 5 June 2025, Cochrane Central Editorial Service rejected our appeal in an email.30 We were told that an independent editor had concluded that the editorial decision was applied correctly. I asked twice who this editor was, noting we were entitled to know this, according to the first of Cochrane’s ten key principles: “Collaboration by fostering global co-operation, teamwork, and open and transparent communication and decision-making.”

It was Jordi Pardo Pardo. All the ideals we had when we created Cochrane were gone. I contributed to formulating the key principles, but Cochrane had become a power base of the worst kind, which I have detailed in three books7,31,32 and numerous articles.33

Pardo’s views on overdiagnosis were void. We argued in our appeal that “The editorial requirement that we need to be able to identify individual women who have been overdiagnosed is misguided and inconsistent with Cochrane standards. It is not possible to identify those who benefit either, but the editors make no similar requirement for this outcome. Our inability to identify individuals who benefit or are harmed by interventions is a main reason why we perform randomised trials and systematic reviews.

With the rejection, the Methods Reviewer brought forward a new argument, which we had not had the chance to respond to previously; namely that the authors of the original trials should use the term ‘overdiagnosis’ to describe the difference in incidence their trials identify. This is not a Cochrane requirement we are aware of. Moreover, the original trial authors have used the term.”34,35

Pardo tried to annul our legitimate explanation by saying that “it does not deny the fact that we don’t know how many of the diagnosis [sic] are real overdiagnosis.” This is an invalid argument. Overdiagnosis is a statistical issue; namely the detection of cancer lesions that would otherwise not have been detected in the women’s remaining lifetime. Denmark is the only country in the world that allows accurate estimation of overdiagnosis in practice because we had screening in only 20% of the population for 17 years. We found 33% overdiagnosis,36 which is very close to the 31% more lumpectomies and mastectomies we reported in our Cochrane review of the randomised trials.13 But this time, we were not allowed to mention our highly relevant Danish population study.

Pardo noted that it requires a “pre-specified process” and a protocol if authors want to mention observational studies in the Discussion section. We had questioned the validity of this request, which we believe is not a formal Cochrane policy. In fact, it is quite common in Cochrane reviews, including some of our own, e.g. our review of melanoma screening,27 to mention observational studies without having a formal protocol for this. We nonetheless deleted all observational studies from our Discussion apart from a few that were particularly useful for the readers to know about.23

Pardo criticised that we wrote in our Conclusions that the most reliable trials did not support that breast screening reduces breast cancer mortality for any age group, and that we believe the time has come to reassess whether universal mammography screening should still be recommended. Yet again, we were accused of having pre-conceived ideas about no benefit of screening “rather than considering it may actually have benefit not detected.”

Why should we conclude that a benefit might have been overlooked after 600,000 women had participated in trials that showed no effect on cancer mortality or total mortality (risk ratios of 1.00 and 1.01, respectively)? And, as required by the editors, we wrote in the summary of findings of the review that “mammography may have little or no effect on breast cancer mortality.”

Cochrane Prefers Substandard Research Conducted by Conflicted Authors

We had informed the editors that our assessments of the risk of bias in the individual trials were the same as in previously published versions of our review and that the rejection of our assessments by the editors was therefore a rejection of previous peer reviews and editorial decisions.

A key issue was the two Canadian trials (CNBSS). Pardo noted that a 2024 review37 conducted by David Moher et al. for the Canadian Task Force had changed the reliability of these trials from moderate to high risk of bias compared to the 2017 review by the same task force for the domains of randomisation generation and allocation concealment because new evidence had emerged.

So, what was the new evidence about these 32-year-old trials? There was none! Moher et al. wrote that “Concerns about the CNBSS have been raised about the inclusion of symptomatic patients, potentially biased randomization, as well as the quality of mammography [18–22].”37

The five references were to articles written by staunch screening advocates, which included Martin Yaffe, Daniel Kopans, Stephen Duffy, and Norman Boyd. I have documented that some of these authors have published highly misleading, and in some cases fraudulent, papers about the alleged benefits of mammography screening.2,3

What Moher et al. and Pardo wrote was false. First, no new evidence has emerged. Second, we wrote in all versions of our Cochrane review that “An independent review of ways in which the randomisation could have been subverted uncovered no evidence of it.”38 Third, the screened and the control groups were very similar for important prognostic factors. This contrasted with all the other trials, none of which reported fully on any prognostic factor in the two randomised groups apart from age, and several of which had differences in age.3,13 Fourth, the quality of the Canadian mammograms was so good that the detected tumours were smaller, on average, than those detected in other contemporary trials.39

The reason why screening advocates have tried to discredit the Canadian trials for 33 years is that they did not find an effect of screening on breast cancer mortality. Radiologist Daniel Kopans and Martin Yaffe, also a radiologist and co-author of the Moher review, have been particularly aggressive. In 2021, Yaffe once again accused the Canadian investigators of scientific misconduct, having manipulated with the randomisation, and called for retraction of the publications.40 This led the University of Toronto to conduct a formal investigation chaired by Mette Kalager, the previous leader of the Norwegian breast screening programme. I was one of the persons Mette interviewed because I have detailed knowledge of the trials.

Mette delivered her report to the University 1.5 years ago but despite my repeated requests to see the report, the University has refused, even after I sent a formal Freedom of Information request, which was rejected because anything to do with research is exempted. I was told that the report would be released “in the near future,” but I have experienced that this can mean five years when the issue is inconvenient for the administrators. According to Mette, the committee did not find any scientific misconduct or important issues with the trials, and it is a huge scandal that the University has not exonerated the researchers long ago. Insiders suspect the university is afraid of litigation by aggressive radiologists with deep pockets, which has been an issue several times before,2,3 and while nothing is done, Yaffe continues to harass the innocent investigators.40

It is a sign of Cochrane’s moral decline, which I have detailed in three books,7, 31, 32 that they let conflicted authors decide that the Canadian trials should be considered at high risk of bias. Pardo opined that the Moher review provides a useful example on how we could have addressed the editorial concerns about our review. This is ironic because the Moher review is a poor-quality, politically expedient review.

Even though we documented at length in our Cochrane review that breast cancer mortality is a biased outcome that favours screening, and that we therefore need to look at cancer mortality, including breast cancer mortality, the Moher review didn’t alert their readers to this bias and did not report on total cancer mortality, which is inexcusable. We reported in our 2013 Cochrane review that “The major difficulty in assessing cause of death might have occurred when the patients were diagnosed with more than one malignant disease” and that all-cancer mortality was not reduced (risk ratio 1.00, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05).13

Since chemotherapy and radiotherapy of overdiagnosed cancers increase mortality,13 total mortality is the only unbiased mortality outcome. As noted above, in our updated review that Cochrane refused to publish, we found that all-cause mortality was not reduced either (risk ratio 1.01, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.04).14,19

The Moher review found overdiagnosis rates of 9-11%, which is far below the true rates, as derived from the randomised trials and the most reliable observational studies where they were 31%13 and 52%,41 respectively. Moher et al. don’t even accept overdiagnosis as a reality, as they write that overdiagnosis can be associated with breast cancer screening. No, it is an inevitable consequence of screening, and it is caused by screening.

Even worse, they falsely claimed that screening reduces all-cause mortality and gave estimates for the number of deaths saved per 1,000 in various age groups.

Conclusions

We established the Cochrane Collaboration based on enthusiasm, collaboration, and a quest for the truth, challenging authorities, dogma, and corporate interests. This wonderful creation has degenerated into a politically expedient organisation that doesn’t care much about the trustworthiness of the science or the public it is meant to serve.

In relation to my published Cochrane reviews, in widely different areas, I have encountered numerous instances of serious editorial misconduct, protection of guild and financial interests, and gross incompetence,7,31,32 but the story about our update of the mammography screening review is the final nail in the coffin and marks the requiem for Cochrane.

The huge scandal in 2001, where we were not allowed to publish the major harms of screening should have made the Cochrane leaders handle our update with utmost care but they behaved like bulls in a China shop, wrecking Cochrane’s reputation. Cochrane’s motto, “Trusted evidence,” has become a joke.

Cochrane no longer serves its patients – it serves itself. Lost in its own navel-gazing, it now prioritises keeping colleagues and authorities comfortable rather than delivering trustworthy and timely science.

I recently interviewed my good friend, Professor John Ioannidis from Stanford, the world’s most cited medical researcher, about Cochrane for our film and interview channel, Broken Medical Science.42 I said that I hoped Cochrane would rise from the ashes and survive and build a better Cochrane without the problems that led to my expulsion five years ago.7,31,32

John replied: “I would fully agree with such a plan for a renovation, rejuvenation, a resurrection, recasting of a vibrant Cochrane and I do hope that this can happen because there is tremendous talent, tremendous commitment from lots of people who would feel completely orphaned if Cochrane Collaboration, for example, becomes entangled into for-profit agendas. They would feel completely orphaned if Cochrane becomes more and more bureaucratic.”

These were our hopes for Cochrane. But it is too late now. Cochrane is on a suicide mission and will soon disappear into oblivion. What a shame.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

1 Sjönell G, Ståhle L. Hälsokontroller med mammografi minskar inte dödlighet i bröstcancer. Läkartidningen 1999;96:904-13.

2 Gøtzsche PC. Mammography screening: The great hoax. Copenhagen: Institute for Scientific Freedom 2024 (freely available).

3 Gøtzsche PC. Mammography screening: truth, lies and controversy. London: Radcliffe Publishing; 2012.

4 Gøtzsche PC, Olsen O. Is screening for breast cancer with mammography justifiable? Lancet 2000;355:129-34.

5 Horton R. Screening mammography – an overview revisited. Lancet 2001;358:1284-5.

6 Wilcken N, Ghersi D, Brunswick C, et al. More on mammography. Lancet 2000;356:1275-6.

7 Gøtzsche PC. Whistleblower in healthcare. Copenhagen: Institute for Scientific Freedom; 2025 (Autobiography; freely available).

8 Olsen O, Gøtzsche PC. Cochrane review on screening for breast cancer with mammography. Lancet 2001;358:1340-2.

9 Olsen O, Gøtzsche PC. Systematic review of screening for breast cancer with mammography. Lancet 2001;Oct 20.

10 Olsen O, Gøtzsche PC. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;4:CD001877.

11 Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:CD001877.

12 Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;4:CD001877.

13 Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2013;6:CD001877.

14 Gøtzsche PC. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Copenhagen: Institute for Scientific Freedom 2023; May 3.

15 First set of Cochrane peer reviews, 91 points, 21 pages. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2024; Feb 6.

16 Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009 18;151:W65-94.

17 Zorzela L, Loke YK, Ioannidis JP, et al. PRISMA harms checklist: improving harms reporting in systematic reviews. BMJ 2016;352:i157.

18 Our reply to first set of Cochrane peer reviews. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2024; March 22.

19 Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Updated Cochrane review 2024; June 6:medRxiv preprint.

20 Second set of Cochrane peer reviews, 38 points, 34 pages. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2024; Aug 29.

21 Gøtzsche PC. Cochrane reviews of psychiatric drugs are untrustworthy. Mad in America 2023; Sept 14.

22 Our reply to second set of Cochrane peer reviews. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2024; Nov 22.

23 Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Unpublished update of our 2013 Cochrane Review, CD001877. Submitted to Cochrane on 20 Nov 2024.

24 https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-15#section-15-6-4.

25 Cochrane’s rejection of our updated review, 62 pages. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2025; Feb 26.

26 Our appeal of Cochrane’s rejection of our updated review. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2025; March 24. Attachment 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

27 Johansson M, Brodersen J, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;6:CD012352.

28 Guidance: Criteria for a population screening programme. UK National Screening Committee 2022; Sept 29.

29 Gøtzsche PC. Mammography screening is harmful and should be abandoned. J R Soc Med 2015;108:341-5.

30 Cochrane’s rejection of our appeal. Institute for Scientific Freedom 2025;June 5.

31 Gøtzsche PC. Death of a whistleblower and Cochrane’s moral collapse. København: People’s Press; 2019.

32 Gøtzsche PC. The decline and fall of the Cochrane empire. Copenhagen: Institute for Scientific Freedom; 2022 (freely available).

33 https://www.scientificfreedom.dk/research/.

34 Zackrisson S, Andersson I, Janzon L, et al. Rate of over-diagnosis of breast cancer 15 years after end of Malmö mammographic screening trial: follow-up study. BMJ 2006;332:689-92.

35 Baines CJ, To T, Miller AB. Revised estimates of overdiagnosis from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Prev Med 2016;90:66-71.

36 Jørgensen KJ, Zahl PH, Gøtzsche PC. Overdiagnosis in organised mammography screening in Denmark. A comparative study. BMC Women’s Health 2009;9:36.

37 Bennett A, Shaver N, Vyas N, et al. Screening for breast cancer: a systematic review update to inform the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care guideline. Syst Rev 2024;13:304.

38 Bailar JC 3rd, MacMahon B. Randomization in the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: a review for evidence of subversion. CMAJ 1997;156:193-9.

39 Narod SA. On being the right size: A reappraisal of mammography trials in Canada and Sweden. Lancet 1997;349:1849.

40 Yaffe M. Guest post: University of Toronto should take action on flawed breast screening study. Retraction Watch 2025;April 28.

41 Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. Overdiagnosis in publicly organised mammography screening programmes: systematic review of incidence trends. BMJ 2009;339:b2587.

42 Why did Cochrane expel Peter Gøtzsche? Interview with John Ioannidis. Broken Medical Science 2025; Feb 9.

-

Dr. Peter Gøtzsche co-founded the Cochrane Collaboration, once considered the world’s preeminent independent medical research organization. In 2010 Gøtzsche was named Professor of Clinical Research Design and Analysis at the University of Copenhagen. Gøtzsche has published more than 97 papers in the “big five” medical journals (JAMA, Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine, British Medical Journal, and Annals of Internal Medicine). Gøtzsche has also authored books on medical issues including Deadly Medicines and Organized Crime. Following many years of being an outspoken critic of the corruption of science by pharmaceutical companies, Gøtzsche’s membership on the governing board of Cochrane was terminated by its Board of Trustees in September, 2018. Four board resigned in protest.