Gold is booming – but how safe is it for investors, really?

Theo Leggett

International business correspondent

BBC

BBC

Listen to Theo read this article

“What you have there is about £250,000 worth of gold,” Emma Siebenborn says as she shows me a faded plastic tub filled with old, shabby jewellery – rings, charm bracelets, necklaces and orphaned earrings.

Emma is the strategies director of Hatton Garden Metals, a family-run gold dealership in London’s Hatton Garden jewellery district, and this unprepossessing tub of bric-a-brac is a small sample of what they buy over the counter each day. It is, in effect, gold scrap, which will be melted down and recycled.

Also on the table, rather more elegantly presented in a suede-lined tray, is a selection of gold coins and bars. The largest bar is about the size and thickness of a mobile phone. It weighs a hefty 1kg, and it’s worth about £80,000.

The coins include biscuit-sized Britannias, each containing precisely one ounce of 24 carat bullion, as well as smaller Sovereigns. These are all available to buy – and the recent surge in gold prices has led to a surge in demand.

Zoe Lyons, who is Emma’s sister and the managing director, has never seen anything like it – often she finds would-be sellers queuing in the street. “There’s excitement and buzz in the market but also nervousness and trepidation,” she tells me.

“There’s anxiety about which way the market is going to go next, and when you get those emotions, ultimately it creates quite big trades.”

At MNR jewellers a couple of streets away, a salesman agrees: “Demand for gold has increased, definitely,” he says.

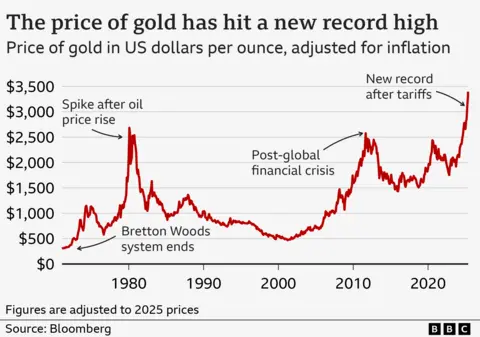

Gold is certainly on a roll. Its price has increased by more than 40% over the past year. In late April it rose above $3,500 (£2,630) per troy ounce (a measurement for precious metals). This marked an all-time record, even allowing for inflation, exceeding the previous peak reached in January 1980. Back then the dollar price was $850, or $3,493 in today’s money.

Economists have attributed this to a variety of factors. Principal among them has been the unpredictable changes in US trade policy, introduced by the Trump administration, the effects of which have shaken the markets. Gold, by contrast, is seen by many as a solid investment. Fears about geopolitical uncertainty have only added to its allure. Many investors have come to appreciate the relative stability offered by a commodity once dismissed by the billionaire Warren Buffett as “lifeless” and “neither of much use nor procreative”.

“It’s the kind of conditions that we consider a bit of a perfect storm for gold,” explains Louise Street, senior markets analyst at the World Gold Council, a trade association funded by the mining industry.

“It’s the focus on potential inflationary pressures. Recessionary risks are rising, you’ve seen the IMF [International Monetary Fund] downgrading economic forecasts very recently…”

But what goes up can also come down. While gold has a reputation as a stable asset, it is not immune to price fluctuations. In fact, in the past, major surges in the price have been followed by significant falls.

So what is the risk this could happen again, leaving many of today’s eager investors nursing big losses?

What really triggered the goldrush

Helped by its relative rarity, gold has been seen as an intrinsic store of value for centuries. The global supply is limited. Only around 216,265 tonnes have ever been mined, according to the World Gold Council, (the total is currently increasing by about 3,500 tonnes per year). This means that it is widely perceived as a “safe haven” asset that will retain its value.

As an investment, however, it has both advantages and disadvantages.

Unlike shares, it will never pay a dividend. Unlike bonds, it will not provide a steady, predictable income, and its industrial applications are relatively limited.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The draw, however, is that it is a physical product that exists outside of the banking system. It is also used as an insurance policy against inflation: while currencies tend to lose value over time, gold does not.

“Gold can’t be printed by central banks, and it can’t be conjured out of thin air,” says Russ Mould, investment director at stockbroker AJ Bell. “In recent times, a big policy response from authorities when there’s been a crisis has been: slash interest rates, boost money supply, quantitative easing, print money. Gold is seen as a haven from that, and therefore a store of value.”

There has recently been a significant rise in demand for gold from so-called Exchange Traded Funds, investment vehicles that hold an asset such as gold themselves, while investors can buy and sell shares in the fund.

They are popular with large institutional investors – and their actions have helped to push up the price.

When gold hit its previous record in January 1980, the Soviet Union had just invaded Afghanistan. Oil prices were surging, driving up inflation in developed economies, and investors were looking to protect their wealth. The price also rose sharply in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, leading to another peak in 2011.

The recent increases appear to owe a great deal to the way markets have responded to the confusion triggered by the Trump administration.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

The most recent surge came after US President Donald Trump launched an online attack on Jerome Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve. Calling for immediate interest rate cuts, he described Mr Powell as a “major loser” for failing to reduce the cost of borrowing quickly enough.

His comments were interpreted by some as an attack on the independence of the US central bank. Share markets fell, as did the value of the dollar compared to other major currencies – and gold hit its most recent record.

But gold’s recent strength is not wholly explained by the Trump factor.

Fears of weaponisation of the dollar system

The price has been on a steep upward curve since late 2022, partly, according to Louise Street, because of central banks. “[They] have been net buyers of gold, to add to their official reserves, for the past 15 years,” she explains. “But we saw that really accelerate in the past three years.”

Central banks have collectively bought more than 1,000 tonnes of gold each year since 2022, up from an average of 481 tonnes a year between 2010 and 2021. Poland, Turkey, India, Azerbaijan and China were among the leading buyers last year.

Analysts say central banks may themselves have been trying to build up buffers at a time of growing economic and geopolitical uncertainty.

Getty Images

Getty Images

According to Daan Struyven, co-head of global commodities research at Goldman Sachs: “In 2022 the reserves of the Russian Central Bank got frozen in the context of the invasion of Ukraine, and reserve managers of global central banks around the world realised, ‘Maybe my reserves aren’t safe either, what if I buy gold and hold it in my own vaults?’

“And so we have seen this big structural fivefold increase in demand for gold from central banks”.

Simon French, chief economist and head of research at investment firm Panmure Liberum also believes that independence from dollar-based banking systems has been a major driver for central banks. “I would look at China, but also Russia, their central bank is a big buyer of gold, also Turkey.

Getty Images

Getty Images

“There are a number of countries who fear weaponisation of the dollar system and potentially the Euro system,” he says.

“If they are not aligning themselves with the US or the Western view, on diplomatic grounds, on military grounds… having an asset in their central bank that is not controlled by their military or political foes is quite an attractive feature.”

Another factor may now be helping to drive the gold market upwards: FOMO, or fear of missing out. With new all-time records being set, it has filtered through into everyday conversation in some quarters.

Zoe Lyons believes that this is the case in Hatton Garden. “[People] want a piece of the golden pie,” she says, “and they’re willing to do that through buying physical gold.”

Safe, but for how long?

The big question, though, is what happens next. Some experts believe the upward trend will continue, fuelled by unpredictable US policy, inflationary pressures and central bank buying. Indeed Goldman Sachs has forecast gold will reach $3,700/oz (£2,800/oz) by the end of 2025 and $4,000 (£3,000) by mid 2026.

But it adds that in the event of a recession in the US or an escalation of the trade war it could even hit $4,500 (£3,400) later this year.

“The US stock market is 200 times bigger than the gold market, so even a small move out of the big stock market or the big bond market would mean a big percent increase in the much smaller gold market,” explains Daan Struyven.

In other words, it wouldn’t take a huge amount of turbulence in major investment markets to drive gold upwards.

Yet others are concerned that the price of gold has risen so far, so fast that a market bubble is forming – and bubbles can burst.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Back in 1980, for example, the dramatic spike in the gold price was followed by an equally remarkable correction, dropping from $850 (£640) in late January to just $485 (£365) in early April. By mid-June the following year, it stood at just $297 (£224) – a decline of 65% from its peak.

The peak in 2011, meanwhile, was followed by a sharp dip, then a period of volatility. Within four months it had dropped by 18%. After plateauing for a while, it continued to fall, reaching a low point in mid-2013 that was 35% down from its highest.

The question that remains is, could something similar happen now?

Could the bubble burst?

Some analysts do think prices will ultimately fall significantly. Jon Mills, an industry expert at Morningstar, made headlines in March when he suggested the cost of an ounce of gold could drop to just $1,820 over the next few years.

His view was that as mining firms increased their production and more recycled gold entered the market, the supply would increase. At the same time central banks would ease off their buying spree, while other short-term pressures stimulating demand would subside, bringing prices down.

Those forecasts have since been revised upwards slightly, largely because of increased mining costs.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Daan Stryven disagrees. He believes there could be a short-term dip, but prices will generally continue to rise. “If we were to get a Ukraine peace deal, or a rapid trade de-escalation, I think hedge funds would be willing to take some of their money out of gold and put it into risky assets, such as the stock market…

“So you could see temporary dips. But we are quite confident that in this highly uncertain geopolitical setup, where central banks want safer reserve holdings, that they will continue to push demand higher over the medium term.”

Russ Mould believes there will, at the very least, be a lull in the upwards trend. “Given that it has had such a stunning run, it would be logical to expect it to have a pause for breath at some stage,” he says.

But he believes that if there is a sharp economic slowdown and interest rates are slashed, the gold price could go higher in the long run.

One problem for investors is working out whether the recent record price for gold was simply a staging point in a continued upward climb – to more than $4,000 for example – or the peak.

Simon French at Panmure Liberum believes the peak may now be very close, and people piling into the market now in the hope of making big money are likely to be disappointed. Others have warned that those recently lured into buying gold by hype and headlines could lose out if the market goes into reverse.

“Short-term speculating can backfire, even though there will be a temptation to hang on to the coat-tails of the record run upwards,” is how Susannah Streeter, head of money and markets at Hargreaves Lansdown, has put it.

“Investors considering investing in gold should do so as part of a diversified portfolio – they shouldn’t put all their eggs in a golden basket.”

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.