Turkey’s ‘tough guy’ president is accused of silencing opponents

Turkey’s ‘tough guy’ president says he’s tackling corruption. Rivals say he’s silencing opposition

Orla GuerinSenior International Correspondent, Istanbul

Orla GuerinSenior International Correspondent, Istanbul

BBC

BBC

For 13 terrifying seconds on 23 April this year, Turkey’s largest city was shaken by a 6.2 magnitude earthquake. It was so strong that 151 people leapt from buildings in Istanbul in panic causing injuries, but no deaths.

But the Mayor, Ekrem Imamoglu, could not lift a finger to help the city he was first elected to run in 2019.

He was behind bars in a high-security prison complex in the district of Silivri, on the western edge of the city – ironically close to the epicentre.

Imamoglu is accused of a raft of corruption charges, which he strongly denies – “Kafkaesque charges” in his words.

Supporters say his only crime is being the greatest threat to Turkey’s leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in presidential elections due by 2028.

YASIN AKGUL/AFP via Getty Images

YASIN AKGUL/AFP via Getty Images

Many of his fellow prisoners in Marmara jail – on the day of the earthquake – had also fallen foul of President Erdogan during his 22 years in power, some of them as peaceful protesters.

The jail is still widely known by its former name of Silivri. Hence the household phrase to explain why the speaker might be wary of criticising Erdogan: “Silivri is cold now.”

Critics say that after Erdogan’s early years as a Western-facing reformer, he has become a latter-day Sultan, dismantling human rights, cracking down on dissent and weaponising the courts.

The jailed mayor, leaders of his Republican People’s Party (CHP), veteran lawyers, and student protesters are all appearing in the dock this month in separate cases.

“Erdogan has taken a huge step towards turning Turkey into a Russia-style autocracy,” argues Gonul Tol, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute (MEI) in Washington, who is from Turkey and now lives in the US.

“What he has in mind is a Turkey where the ballot box has no meaning… where he hand-picks his opponents.”

Ozan Guzelce/ dia images via Getty Images

Ozan Guzelce/ dia images via Getty Images

In all, more than 500 people linked to the CHP have been arrested since last October.

Prosecutors accuse the mayor and his associates of taking bribes, rigging tenders, extortion, and having links to terrorism.

But the CHP – which is centrist and secular – argues that the detentions are politically motivated and aimed at silencing the opposition. The party denies the charges.

Some are asking why, as Turkish democracy comes under fire in full view, has the international community said little and done even less? Could it be that Erdogan has fingers in too many pies – including Russia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nato – for European leaders to want to pick a fight?

And is US President Donald Trump’s willingness to look the other way on human rights giving Erdogan a freer hand?

‘Overstepping the boundaries of justice’

Moments before his arrest in March, with hundreds of police on his doorstep, Mayor Imamoglu calmly carried on knotting his tie, while making a social media video for his supporters.

“We are facing great tyranny,” he said, “but… I will not be discouraged.”

He was composed and defiant – and “a mortal threat to Erdogan”, according to Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish research programme at the Washington Institute in the US.

“He’s charismatic, he’s relatable, he’s conservative like Erdogan, but also secular. He ticks so many boxes.”

But he can tick far fewer in jail.

Burak Kara/Getty Images

Burak Kara/Getty Images

His arrest came just as the CHP – Turkey’s largest opposition party – was poised to nominate him as their candidate for the presidency. (They did it anyway, after he was detained.)

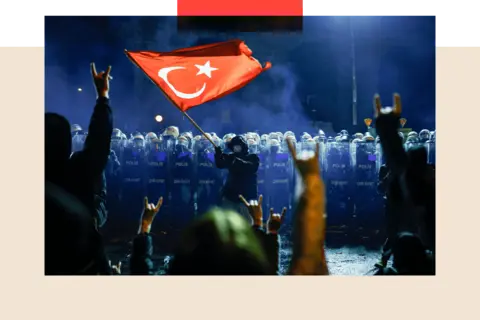

Locking up Imamoglu sparked the biggest anti-government protests in more than a decade. It was mostly the young who surged onto the streets, members of Generation Erdogan who have known no other leader.

“It has reached the breaking point for most people,” said one 21-year-old in Istanbul. “They have overstepped the boundaries of justice.”

Another said this was “a direct attack on our democracy”.

The government banned the demonstrations – which were largely peaceful – but could not stop them.

The turmoil in Istanbul played out in the shadow of a Roman aqueduct. Erdogan’s legions of riot police took up positions under the arches, armed with batons, tear gas and rubber bullets.

KEMAL ASLAN/AFP via Getty Images

KEMAL ASLAN/AFP via Getty Images

One photo made front pages around the world: a lone protester dressed as a whirling dervish – in traditional costume plus gas mask – being pepper-sprayed by the police.

Hours after it was taken, the photographer, Yasin Akgul of the AFP news agency, was detained at home, his hands still stinging from tear gas. Several other leading photojournalists were also arrested.

Some 2,000 people were rounded up after the protests – many in pre-dawn raids. More than 800 of them were charged with taking part in “unauthorised demonstrations”.

These days, getting arrested is “the easiest thing”, according to Gonul Tol. “You just have to like a tweet or a Facebook post criticising Erdogan.”

Student protester Esila Ayia, 22, was detained after holding up a poster calling the Turkish leader a dictator. (Insulting the president is a crime in Turkey.) If convicted, she could get four years in jail.

YASIN AKGUL/AFP via Getty Images

YASIN AKGUL/AFP via Getty Images

The arrests keep coming

Many Turks are feeling the chill, according to Berk Esen, associate professor of political science at Istanbul’s Sabanci University, which has a liberal reputation. He claims there is “rampant pressure and oppression” of opposition figures in politics, civil society, academia and the media.

But he adds that Turkey is “not yet a fully fledged authoritarian regime… there is still some room for dissent”.

Yet the arrests keep coming. More than 100 CHP members remain behind bars.

The president claims the CHP is “mired in corruption” with a network like “an octopus whose arms stretch to other parts of Turkey and abroad”.

But Emma Sinclair-Webb of the campaign group Human Rights Watch sees a different octopus – the government itself.

It has “many, many, many, tentacles that go everywhere”, she says. “There is a clear-sighted attempt by the government to go after critics and to go after the opposition.

Ugur Yildirim/ dia images via Getty Images

Ugur Yildirim/ dia images via Getty Images

“There is a complete loss of trust in the justice system. It’s perceived more and more as highly politicised, and detention is being used to muzzle critics.”

Members of the judiciary, prosecutors and judges themselves are “all the time looking up for instructions from above”, she says.

The government says the judiciary is independent and impartial.

‘He’s a tough guy – very smart’

As Istanbul’s mayor remains behind bars in Silivri, the international community remains focused elsewhere – chiefly on Israel’s war in Gaza, and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The latter gives President Erdogan an edge, according to analysts.

He enjoys relatively good relations with Vladimir Putin, and Volodymyr Zelensky as well as Trump.

“I can’t think of many other leaders who are in this position,” says Berk Esen of Sabanci University. “I think in the international arena he likes to present himself as a dealmaker, in the room, shaking hands.”

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty Images

President Erdogan has had some success – for instance, helping to broker an agreement for Ukraine to resume grain exports through the Black Sea in July 2022, after they were halted by Russia’s invasion five months earlier. And this year he hosted negotiators from Kyiv and Moscow for their first face-to-face talks since 2022.

“Everyone is praising his role in Russia and Ukraine,” says Dr Tol. “Western leaders are looking to him to build European defence. And Trump doesn’t care [what Erdogan does domestically], so he understands he can get away with it. “

She says Trump’s return to the White House “has created an international context where regional autocrats feel empowered”.

Dr Cagaptay, of the Washington Institute, says Erdogan has a freer hand because Trump has turned inwards, and the two leaders have “a special chemistry, going back to Trump’s first term in office”.

“I happen to like him, and he likes me,” Trump has said of Erdogan. “He’s a tough guy and he’s very smart.”

Erdogan is also well-placed geopolitically. Turkey’s land mass lies partly in Asia, and partly in Europe, a bridge between two continents.

He holds plenty of other cards too – not least his leverage in neighbouring Syria. He backed the winning side there, supporting the Islamist rebels who overthrew President Bashar al-Assad in December.

He also leads the only Muslim nation in Nato, with the second largest army in the alliance, and a population of 85.6 million people. What happens here matters, for East and West.

“What Turkey is doing under Erdogan is leveraging its multiple identities very successfully,” says Dr Cagaptay. “With the EU, I think Turkey is playing a middle power game very well…. whether it’s about stabilising Syria or stabilising Ukraine after a ceasefire.”

The sanctity of the ballot

Erdogan may be empowered – and enabled – but there is a limit, according to some analysts.

What he won’t do is cancel the next presidential elections, according to Onur Isci, professor of history and international affairs at Kadir Has University in Istanbul.

“Historically the Turkish people have been acutely sensitive about the sanctity of the ballot and attempts to curtail it would provoke serious consequences,” he says.

Turkish elections are generally free on the day, though far from fair beforehand.

The playing field is not level. Most mainstream media outlets are pro-government. Those that are not, come under strong pressure from the authorities.

Burak Kara/Getty Images

Burak Kara/Getty Images

During the last election in 2023, Erdogan hung on to power narrowly, winning 52.18% of the vote against the opposition candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

Recent polls have suggested he could be beaten next time by Imamoglu. But the mayor remains behind bars, facing several different trials, and the opposition will probably be forced to choose a different candidate.

As a two-term president, Erdogan, 71, is barred from running again, but he can solve that problem by calling early elections or bringing in a new constitution.

“I have no interest in being re-elected or running for office again,” he said in May.

Mr Esen thinks otherwise. “He will run for the presidency as long as he is alive.”

KEMAL ASLAN/AFP via Getty Images

KEMAL ASLAN/AFP via Getty Images

As the longest-serving leader in modern Turkey, he has a loyal base who want him to. Many conservative voters are grateful for the development brought by his Justice and Development Party (AKP) and for his promotion of Islam, in this secular republic.

Plenty of devotion was visible at a rally of the president’s supporters before the last election.

One supporter, Ayse Ozdogan, had gone there early to hear her leader’s every word, a crutch by her side.

“Erdoğan is everything to me,” she said, with a broad smile. “We couldn’t get to hospitals before, now we have transportation. He has improved roads. He has built mosques.”

But what of his impact on Turkish democracy?

“It’s hugely eroded but not dead,” according to Ms Sinclair-Webb. “There is a very vibrant democracy, wedded to democratic principles and to elections.”

The opposition too is very robust, she says.

Soner Cagaptay cites the example of a doner kebab seller, slicing meat on a spit.

“To me, that’s like Turkish democracy under Erdogan. He’s taken really thin slices over the past 20 years, and there’s very little meat left.”

But he says there is a lesson to take from the Erdogan era: “It takes a long time to kill a democracy.”

We contacted the president’s communication office for an official response but did not receive one.

In a report to the United Nations Human Rights Council, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs here said that Turkey has “stood firm to protect and promote human rights… and has continued its efforts at further compliance with international standards in law.”

The report adds that they country “spares no effort to create favourable conditions for civil society, including human rights defenders”.

That may ring hollow in the cells in Silivri.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Recent Top Stories

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.