Trump’s tariffs add to fears in the UK’s struggling steel towns

Trump’s tariffs are looming large over the UK’s last surviving steel towns

Simon Jack, Business editor, and Huw Thomas, Business correspondent for BBC Wales

BBC

BBC

Ryan Davies worked at the Port Talbot steelworks for 33 years and from his very first day, he heard rumours that the plant was on the verge of closing.

Whispers would spread among his colleagues about new ownership and redundancies. Usually, they weren’t true.

“You took it with a pinch of salt,” he recalls.

It was an exhausting job. He remembers the clanging of metal and the high-pitched whining of steam, as well as the fear of gas leaks. In the summer it became “excruciatingly” hot inside the plant and his shifts lasted 12 hours.

But he also valued his job. Being a steelworker was part of his identity.

Then, a few years ago, he heard a new rumour: that Tata Steel, the plant’s Indian owners, was to close its blast furnaces. This one turned out to be true.

The two furnaces were switched off in July and September last year, part of a restructure that would ultimately remove around 2,000 jobs, half of the number employed there.

PA Media

PA Media

“It was the end of it all – the end of 100 years of steelmaking in Port Talbot,” says Mr Davies, who took voluntary redundancy in November.

He is 51 now and unsure about his own future, and what the news means for his wife and his 19-year-old daughter. But he also worries deeply about Port Talbot.

Steel is integral to the town’s identity. The bronze-coloured chimneys loom across the skyline; the first thing you see as you drive towards the town from the M4.

Steel, Mr Davies says, was “the whole reason Port Talbot was ever a successful town”.

It is a similar story across the handful of other British communities that historically relied on steelmaking as a source of employment.

As well as Port Talbot, they include places like Redcar in North Yorkshire and Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire.

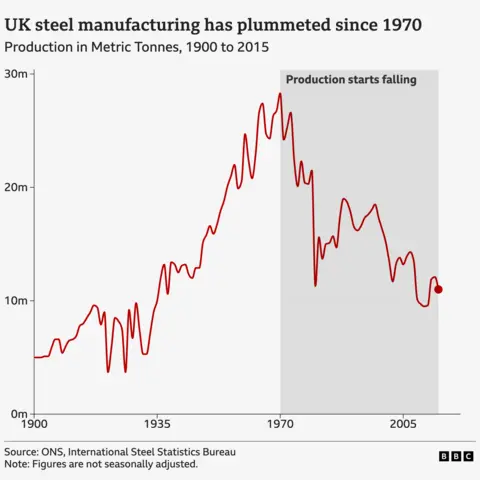

At its peak around 1970, the UK’s steel industry produced more than 26 million tonnes of steel each year and employed more than 320,000 people.

Then came the long decline. Now just four million tonnes are produced each year, with fewer than 40,000 employed.

But in the last few years, the industry has entered a particularly difficult period, thanks in part to rising energy prices. The ongoing uncertainty about tariffs on steel exports to the US is not helping.

This has frayed nerves and cost the UK steel industry orders from US companies, according to steel industry executives.

Getty Images

Getty Images

While 27.5% tariffs on cars were reduced to 10% and tariffs on aerospace products were lowered to zero, a 25% tariff on UK steel and aluminium exports to the US is still in place.

British officials say they are determined to reduce steel tariffs to zero too, and talks are ongoing. But this all adds to a sense of foreboding on the ground in steel towns.

So, what comes next if UK steel manufacturing really does near extinction? And where does that leave places like Port Talbot and Redcar that have so much of their identity bound up in their industrial history?

The ‘wilderness’ ghost steel towns

If you want to peer into a post-steel future, look at Redcar on the northeast coast – an area sometimes described as Britain’s “rust belt”, owing to the derelict industrial sites scattered across the landscape.

Teesside’s steel industry emerged in the mid-19th Century and went on to employ more than 40,000 people. It has long been a point of local pride that the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built from Teesside steel.

But along with other steel towns, it suffered in the latter half of the 20th Century. Cheap imports from China created tough competition. Britain moved from a manufacturing to a service-based economy – and towns like Redcar were left behind.

In 1987, Margaret Thatcher walked with a handbag through a nearby derelict wasteland; a photograph of the “wilderness” visit became a symbol of industrial hardship.

Getty Images

Getty Images

More recently, the steel industry has struggled under the weight of the UK’s relatively high energy prices (which makes it expensive to heat a furnace).

Some analysts also say that the UK’s drive towards decarbonisation is raising costs for steel producers.

In 2015, the Thai owners of Redcar’s steelworks pulled the plug. Sue Jeffrey, then Labour leader of Redcar Council, remembers watching the blast furnace in action, on one of its final days in use.

“It was one of the most devastating things I’ve been involved in,” she recalls.

About 2,000 workers lost their jobs at the site, with thousands more affected through the steel supply chain.

Local businesses were hit too; B&Bs have lost custom from the contractors no longer visiting the area.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The council set up a task force to help former steelworkers into new jobs. It saw some success.

Of the more than 2,000 steelworkers who made an initial claim for benefits when the plant closed, the vast majority had come off benefits within three years, according to a council report published in 2018.

But Ms Jeffrey argues that many could not find jobs that made use of their industrial skills.

Some became dog walkers and decorators; others, chimney sweeps. Many, she says, accepted a large cut in salary.

The same tale has been told in other steel towns; laid-off worker forced to find new jobs.

Some are delighted with the change.

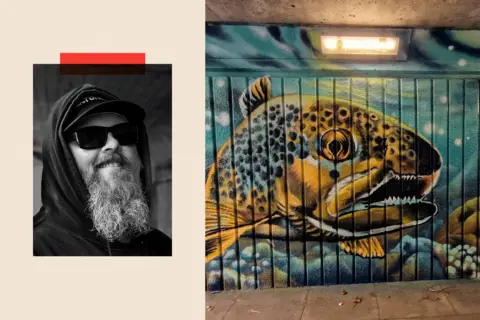

After his redundancy, Ryan Davies decided to pursue his dream since boyhood: street art. He now runs a business, painting murals of ladybirds, ducks and mythical creatures.

Ryan Davies

Ryan Davies

Though his income is lower, he finds it fulfilling. “I’ve been a far happier person since I left,” he says.

“When you’ve got a grey wall and you paint something colourful, it makes people smile.”

But not everyone is so upbeat.

Cassius Walker-Hunt, 28, opened a coffee shop in Port Talbot last year after taking redundancy from the town’s steelworks, using a £7,500 loan from Tata Steel to buy professional coffee-making equipment.

“I’ve been working around the clock just to survive,” he says today.

The fight to keep blast furnaces burning

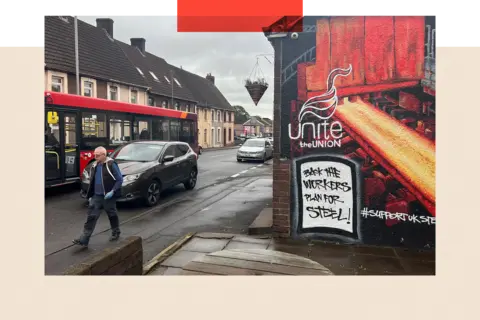

The job security that steelmaking once offered is one reason unions argue it’s imperative to keep the industry alive.

Alun Davies, national secretary at the Community Union, the largest union for steelworkers, thinks governments should step in when required to keep blast furnaces burning.

That’s exactly what happened earlier this year in Scunthorpe, the last place in the UK that makes virgin steel from melting iron ore in blast furnaces.

It has lurched from crisis to crisis. The last government took control when it was on the brink of going bust and – £600million of UK taxpayer support later – sold it to Chinese company Jingye.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Now it is back in government control. The government was forced to intervene after Jingye failed to order vital supplies to keep the furnaces burning.

From here, Scunthorpe’s future is uncertain. Some have urged the Labour government to fully nationalise the site.

But Jonathon Carruthers-Green, an analyst at steel consultancy MEPS International, believes that ministers will be wary of that option because of the huge potential costs and complications.

Alternatively, the plant could be sold to a different foreign buyer.

But, asks Mr Carruthers-Green, “Who is going to come along and start making steel in the UK, where there’s higher [energy] costs, where there’s all sorts of issues around decarbonisation?”

Scunthorpe resident, Sean Robinson, told the BBC earlier this year that he fears the town will become another steel “ghost town”.

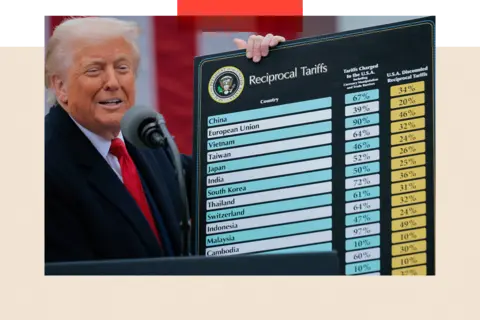

A question of Trump’s tariffs

Looming large over all of this is the question of what will become of Trump’s tariffs and how it will impact UK steel.

The good news is that the UK was exempted from a surprise hike on those tariffs from 25 to 50% last month, and trade officials seem confident that they will also be unaffected by the new deferred date of 1 August, which is when the White House says its most swingeing tariffs on US trading partners will come into effect.

But steel companies are still frustrated that the original plan to reduce tariffs on UK steel to zero is yet to be agreed.

There are two sticking points. The first, according to steel industry sources, is that US trade negotiators are overwhelmed with the sheer volume of work to get through when negotiating with the rest of the world simultaneously.

Getty Images

Getty Images

But the second, and the reason steel was not waved through alongside cars and planes, is that there are concerns in the US that the UK’s largest steel maker Tata no longer makes steel from scratch.

Having closed its blast furnaces, it no longer “melts and pours” the steel but rather imports virgin steel from India to be modified in the UK, leading to some questions in the US as to whether it even counts as UK steel.

Even if and when a zero-tariff deal is done on steel, it is likely to include quotas above which tariffs will be charged, putting a ceiling on future growth in exports to the US.

Is ‘romanticism’ blocking sensible debate?

There is, however, a bigger, more profound question that steel towns must wrestle with. In a post-industrial age, what exactly are these places for?

And, should they try to reignite the embers of their dying steel trade – or pivot to a new industry of the future?

Some trade union leaders maintain that steel towns can, in effect, remain steel towns. With the right investment in green technologies, Mr Davies of the Community Union thinks, a new, cleaner steel industry could emerge.

“Imagine Port Talbot without any steelworkers – it’s unthinkable,” he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

But others think that view is unrealistic. Paul Swinney, a director at the Centre for Cities think tank, argues that there is a certain romanticism in the debate around steel that blocks sensible thinking.

“I think it’s wrapped up in what some people perceive as being ‘good jobs,'” he says. “You did a hard day’s graft, you got your hands dirty, and you felt like you’d contributed. [But that framing] just isn’t helpful.”

As he sees it, “there’s no plausible route forward which is going to have more of these kinds of jobs. “The UK economy has changed,” he argues.

Instead, he believes towns like Port Talbot and Redcar should look to industries of the future.

Industries of the future

Redcar is already taking steps in this direction. The derelict land that once housed the town’s steelworks is now at the centre of an ambitious redevelopment led by the South Tees Development Corporation.

The old steelmaking structures have been flattened to make way for renewable energy and carbon capture and storage.

The managers of the Teesworks project say they have created more than 2,000 “long-term” jobs – and they hope to create 20,000 in total.

But last year, a central government review criticised “inappropriate decisions and a lack of transparency” at the corporation, and looked at why private property developers had ended up owning a large amount of the site.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Tees Valley Conservative Mayor Lord Houchen, who at that point chaired the corporation, said he “welcomed” the panel’s recommendations to improve transparency.

Speaking on local radio in May, he said the Teesworks project has provided “billions of pounds of investment for the region”.

But Mr Swinney of Centre for Cities says we need to think bigger still. Rather than trying to recreate their industrial glory, steel towns may want to lean into white-collar, knowledge economy jobs – the sort of work that made many city centres comparatively rich.

The key is to improve transport from steel towns to cities, where office jobs tend to be located, he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

But ex-steelworker Ryan Davies laughs at the suggestion of steelworkers slipping seamlessly into office jobs.

“When you come from an environment of 33 years of steelworking, going into an office is such a radical difference,” he says.

There are other challenges too: people in steel towns tend to have fewer formal qualifications – often essential for office work.

For example, about 37% of working-age adults in Port Talbot have the equivalent of one year of university education, versus a UK average of 49%.

A slow death vs hope for the future

Ultimately, the future of these towns may rest on the wider fate of the UK’s steel industry. And there is some cause for optimism.

The government insists that Scunthorpe and the rest of the UK steel industry has a future, not least because of the big increase in spending on a steel-intensive defence industry.

Mr Carruthers-Green thinks that the UK’s decarbonisation drive could also eventually play to steel’s advantage.

With more investment in green energy, he says, there will be further demand for the sort of high-quality steel used in things like wind turbines. This, in turn, creates more energy, lowering prices for steel producers.

“The hope is we can get into this virtuous spiral,” he adds.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Gareth Stace, director general of the trade group UK Steel, is a little more cautious, however. There’s a “worst case” scenario where the UK “continue[s] to make less and less and less, he argues.

As he puts it, “We don’t go out of business in one bang”. Instead, there’s a slow death.

Yet he also believes that with some tailored policies, steel could be revived even in this scenario. In particular, he wants to see action on energy prices, as well as policies on procurement in which government departments buy more steel from the UK instead of from abroad.

“If it works,” he says, “for the first time in a very, very long time, we’ll actually have some hope for the future.”

Additional reporting: David Macmillan

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.